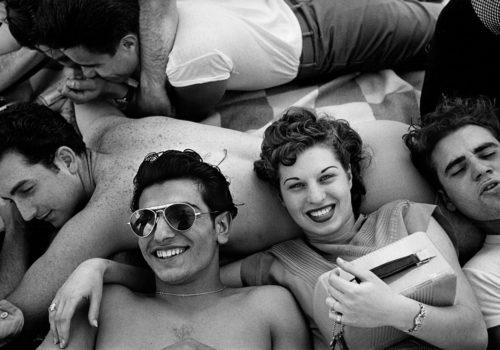

Sixty-three works by Klavdij Sluban are currently on display in Geneva, including photographs exhibited for the first time, Les Lits (2013), and Les Spasmes (2020).

Les Lits (Beds)

After years of photographing prisons and detainees in France and Eastern Europe, Klavdij Sluban returned to Fleury-Mérogis, this time to photograph the beds of detainees, “an elsewhere without a place”, says the photographer.

In this elsewhere, the Beds photographed by Klavdij Sluban are above all a work on presence and absence. Spectral presence of inmates yet absent from the photographs, present with all their bodies, all their dreams, in the folds left there, intimate, true. Absence is one of the great themes that runs through the work of the photographer and traveler who is Sluban: the absence in the distance of prisons, the absence of those whom we meet along the paths but who we will not see again, the absence while “Happy Days on the Isle of Desolation” flow (video, 2017). The absence of time, too, or its immeasurable flow.

But Klavdij Sluban also carries out a great classical exercise in the study of sheets and drapes, a neo-baroque study of the folds, those folds which have always existed in the arts as in philosophy, from the fabrics of Greek statuary to the drapery of the nobles of the renaissance , from Leibniz to Deleuze. Everything folds, unfolds, and folds again, and the soul is a “monad” without door or window, full of dark folds “which draws all its clear perceptions from a dark background.” The folds photographed by Sluban very precisely, draw our clear perceptions from a dark background, through exceptional work on light.

The Beds of Sluban are still a hotbed of cover-up and revelation. In each photograph, an echo of the relative whiteness of the sheets, a black hole in the wall. One immediately thinks of Jean Genet’s only film, Chant d’Amour: two imprisoned men love each other, and one transfers to the other, through the same hole in the wall that separates them, the smoke of his cigarette. Their detained way of making love. The central themes of the prison universe are there, in this hole, with Sluban as with Genet: loneliness, confinement, love and absence, once again. And the eroticism that always nestles in the hollow of the sheets, crumpled, stained, rolled up on themselves.

We will not fail to evoke the thought of Plato who details his concepts of existence, concrete reality, and image. The image of the bed can be made by a painter, a tragedy maker, an illusionist, a poet, a wizard. Or a photographer. Klavdij Sluban is at the same time this photographer, the maker of tragedy and illusions, a poet and a wizard. With a Leica as a wand.

Go Inside. Inside the mental universe of Klavdij Sluban Inside the prison. Inside these beds, this elsewhere, to understand detention. Sluban explains: “The bed is supposed to be the place where the tired body comes to rest. The bed can also accommodate lovemaking, tired lovers … but it is not meant to be a place to live in itself. In Fleury, the bed is a den. If the cell imprisons the young inmate, the bed protects him from the world. Suddenly, the young person spends all his time there. The bed is an elsewhere without a place. ”

Les Spasmes (Spasms)

Who would have expected from Klavdij Sluban a series of baby photos? Baby in the singular. His baby. And who would have thought that in 2020, in the midst of a pandemic, Sluban decided to show this new series without delay, he who usually takes six to ten years to look at his pictures, to select them, to understand them? In this specific case, the photographer felt the urgency. The time of his prison, the time of his journeys on foot through the Balkans, is a long time, which stretches indefinitely. The time of a baby’s first months is a short time. We barely have time to fix the image that he is already another, the little human.

“The baby in my arms is suddenly seized with a terrible spasm that tears him apart before my eyes. We know how to explain so many unnecessary things, but no one has been able to find the cause of these devastating contractions – nor, therefore, to find a cure. Yet it is in poignant pain that this little body tensed like a bow in my arms. To thwart the anguish of the father, a response protocol: freeze these scenes of terror knowing that they will disappear as they appeared. Without explanation. »To photograph, to freeze the scene, and for us who look at the images, scopic enjoyment, haptic enjoyment, existential enjoyment.

The baby screams. You can hear him scream while looking at the photographs. He screams like the man in Munch’s Scream, but at the other end of the spectrum. To him, the anguish of birth, of final separation, of absolute dependence. The primordial anguish. You have to live now. The series could have been called Scream – but Klavdij Sluban chose Spasms. Life is a spasm, starting with an orgasm. Spasms, too, because the baby is thought to be crying because of a stomach ache. In reality, he screams out of existential anguish. Absolute anguish. But when you look at these Spasms long enough, you end up smiling. It’s not Munch. Munch’s Scream doesn’t make you smile. But he, the baby, who cries, who anguishes, he ends up being moving, funny, even euphoric, because yes, little man, we are going to calm your anxiety, momentarily …, we are going to make you grow up, we are you, you are us, you will learn: when you cry, we will feed you, we will help you, we will love you. Look, we have grown up too. We lived. And thanks to you, now we are no longer afraid of dying, you are here, you managed to be born, it is so much more difficult than dying. And Sluban recedes in front of the baby, as he always recedes in front of inmates. In front of the other. The baby is absolute otherness. So, like the great photographer he is, he gives the baby the mirror. The experience of the mirror, long before the age of Lacan. He gives the baby his own image. The photographer disappears, to make way for the baby and his double, in a multitude of cries. And for the first time, Sluban overexposes his photographs. The baby is lost in the whiteness, the cry is choked in the snow. The white leaves room for the only black hole of the mouth.

Barbara Polla, December 18, 2020