by Igor Manko

The Kharkiv art scene in the mid-1980s felt like a bubble ready to blast. With Gorbachev having announced Perestroika, the totalitarian Soviet state was grudgingly loosening its ideological grip, but the emerging freedom (and the freedom of artistic expression as well) was still a moot concept to be defined.

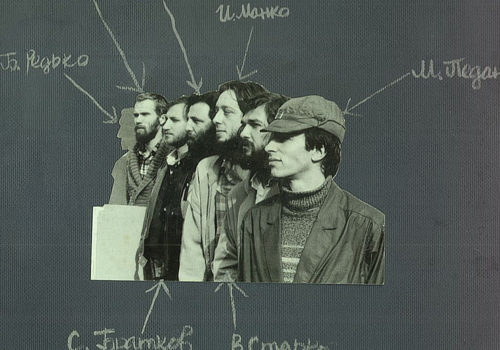

At this time, the community that was soon to be called the Kharkiv School of Photography started filling its ranks with new disciples.

In 1984—1986, several younger photographers who called themselves the Kontakt group gathered in Guennadi Maslov’s tiny lab/studio under the roof of one of the so-called ‘Houses of Culture’ — Soviet establishments that provided space for the various amateur artistic activities of the working class. Theirs belonged to the Union of Construction Workers.

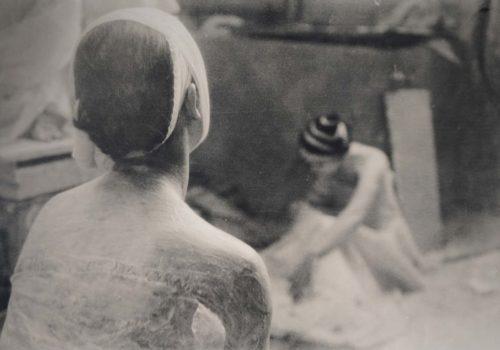

They were producing black-and-white photographs using the closed down aperture when shooting and the ‘point light’ when printing images to achieve extra sharpness and depth of field. They were interested in documentary photography and were influenced by their famous predecessors from the Vremya group, albeit to different degrees. They joined forces to continue and develop the black-and-white documentary line of their senior colleagues’ artistic endeavors and to exhibit as a group. “Nobody really believed that Perestroika would work out, but we all liked the idea that we were allowed to make more noises,” Maslov recalls.

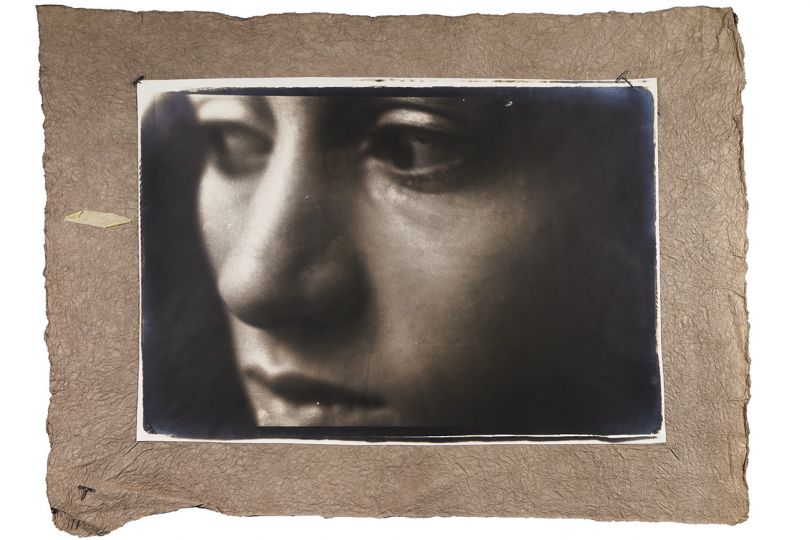

“My work is a translation. It is an attempt to translate the poetry of memories and dreams into the verse of photography — an attempt to catch the fluid material of the subconscious, and put it on a somewhat more stable base of photographic paper,” the artist comments.

“There is no pain here”, claims Boris Mikhailov, criticizing Maslov’s work at the discussion table after the Ukrainian Time exhibition (ArtHouse Gallery, Kharkiv, September 2012). And he is right. Maslov’s (as well as the majority of the Gosprom group artists’) aesthetic grounds deviated from the “merciless documentaries” of their predecessors in search of finer compositional arrangements and more philosophical attitudes. For Maslov, they stem from the Lithuanian photography of the 1980s and the work of Alexander Sliusarev, the head of the so-called Moscow Metaphysical Photography group.

Maslov’s images are sometimes spiced with a sprinkling of absurdity and grotesque so characteristic of life in post-communist societies. The artist’s irony is easily recognizable in the haiku caption found in his Ukrainian Time photo book (2013, Hanna House Books). It could serve as the motto to all the Kharkiv artists’ work of the 1985—2000 period:

Hey, Socialism, old fellow!

Burning down so quietly?

So silently after all?

The group had made several exhibitions when in 1986 Maslov, who was educated as a military interpreter, got a foreign interpreting assignment and left for Ethiopia to earn money for a decent camera. (He did proudly flash a brand-new Nikon 301 when he returned three years later.) His position and his studio were taken by another group artist Vladimir Starko.

Meanwhile, the artistic activity in the city was gaining momentum. Numerous shows opened, sometimes in most inappropriate spaces like gymnasiums, cafes, theater foyers, and stairwells. Starko curated an exhibition of painting and photography on the Construction Workers’ House of Culture premises and was immediately fired for exhibiting West-influenced formalist art alien to Soviet people.

The contemporary audience read Starko’s images as strictly anti-Soviet. His The Window series spoke about the Iron Curtain which banned the Soviet people from access to the rest of the world. The Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star series showcased the deterioration of the main Soviet symbol.

“Photography is a mirror; the camera is like scissors, it cuts out the part of reality corresponding with the artist’s perceptions, thoughts, and even philosophy at the moment of pressing the shutter release button. So any interference with the image, cropping included, is a sign of inferiority as if the photograph itself isn’t good enough,” says the artist.

The group lost its artistic refuge but intensified its activity. In 1987 the artist of the group Misha Pedan got a job at the Students’ Palace, another Soviet ‘big style’ invention. The same year the first grand-scale exhibition of Kharkiv photography (both the first generation and the younger artists), was organized by Pedan, attracting crowds of spectators lining up to enter a large exhibition space (the disco floor) of the Palace. The next day a friendly Deputy Director of the Palace secretly informed Pedan that the exhibition, which violated a whole bunch of Soviet taboos, was about to be closed down by the KGB. The art community resisted those attempts. A public discussion was initiated, which salvaged the show for 10 days and further arose the interest of visitors. The exhibition saw an unprecedented attendance of about 2000 visitors daily.

Pedan’s 1986—1989 The End of La Belle Époque is a street photography project that portrayed the decay of the USSR before its collapse in 1991, a series of images of the late 1980s Kharkiv, its dilapidated streets that nobody cared to maintain, its picturesque inhabitants who all of a sudden found themselves out of the Communist Motherland‘s firm embrace not knowing what to do with this unexpected freedom.

The beginning of the Soviet ‘belle époque’ was marked with Sergei Eisenstein’s red flag ascending over the rebel Potemkin battleship in the 1925 premiere of the film. Battleship Potemkin was black-and-white, and the flag was hand-colored in every frame and every copy of the movie. Misha Pedan’s The End of la Belle Époque depicts its near-death agony in 84 black-and-white pictures. In one of the images, Pedan, in a token handshake with Eisenstein, manually colors red the flags on the Soviet-style mural in each of the 500 numbered and signed copies of the book, as if putting the flag down after the sixty years of its dominance.

It was after the success of that period that the group artists could deservedly consider themselves part of the Kharkiv School of Photography. The group also acquired a new member artist, Sergei Bratkov, who was to become internationally recognized in the 2000s. Now they wanted a new name to reflect the progress, and, after a discussion initiated by Misha Pedan and Leonid Pesin, the group was renamed.

Bratkov has always been interested in making art where “photography plays a secondary or applied role” (T. Pavlova, 2015). His work included placing photographs in glass jars in a cupboard (We All Eat Each Other, 1991), immuring images in a lump of concrete (A Parcel, with Boris Mikhailov), or freezing them in a block of ice (Frozen Landscapes, 1994, an installation in memory of 45 homeless people that froze to death during a cold spell in Kharkiv). But alongside these photo objects, he produced traditional black and white images, collages, and staged photos.

Bratkov’s No Heaven series (45 black-and-white images, 1995) is a very personal picture of his family and himself. A caption under one of the images says: “My Mom and Dad met each other at the time of war. Dad came home on a 3-day leave and met a beautiful girl at a party. He got drunk and threw up onto her white dress. That girl became my Mom.”

1996 Princesses touch upon post-Soviet mentality and women’s rights issues. Four portraits of young females with lowered tights holding semen sample containers in their laps and, apparently, awaiting A Prince Charming, were made in the Kharkiv Center for Reproductive Medicine. The names of real-life European royal heirs are written on the containers.

Bedtime Stories (a.k.a. Horror Stories, 1998) illustrated so-called ‘Horror Verses’, black humor Russian folk poetry popular in the 1980s and ’90s. Here is an example:

A young pioneer was fishing alone,

A maniac killer was all on his own.

Oh, how the old man kept cursing, you guess

The pioneer’s badge got stuck in his ass.

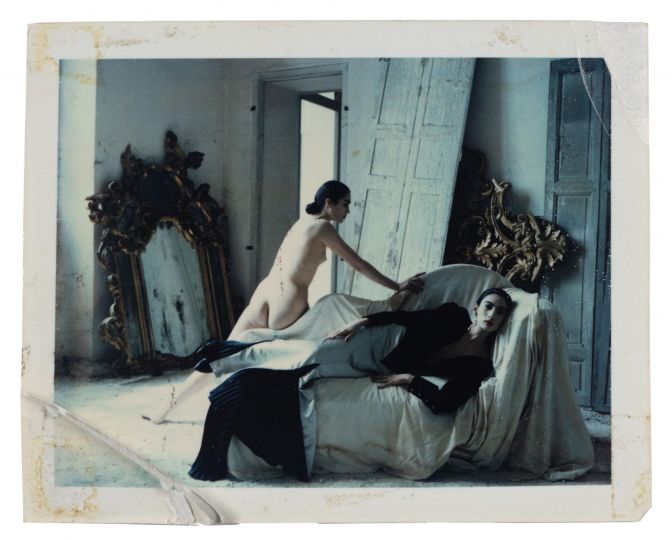

A series of meticulously and theatrically staged images were captioned with the verses.

The Gosprom (Derzhprom in Ukrainian, abbreviated from ‘state industry’) Building is the only internationally known landmark of the city of Kharkiv. It was built in the late 1920s, at the time when Kharkiv was the capital of Soviet Ukraine. Gosprom was constructed using the new cutting edge liquid concrete technology and was an architectural monument to Soviet Constructivism that is now listed in the history of world architecture. It has always been the city symbol and, as such, the name rooted the group into the Soviet past and linked it with the Kharkiv photography present and future — or, so was the artists’ perception of the name and of their role in the Kharkiv School at the time. Almost 10 years later, Sergei Bratkov produced his Gosprom series to commemorate the event.

Influenced by Boris Mikhailov’s work, Redko directed his camera at social issues, but his work is not that critical of Soviet realia. Rather, its humor and grotesque offer an ironic look at the absurdity of everyday life of the late Soviet years, its deteriorating condition, and the Kharkiv residents’ spirit to overcome the disaster.

In 1988 another ‘grand’ exhibition at the Students’ Palace lived for only 4 days before being closed by the Communist Party officials, which resulted in Pedan’s losing his job.

The Gosprom group stayed active on the Kharkiv art scene for several more years, exhibiting their work both locally and internationally.

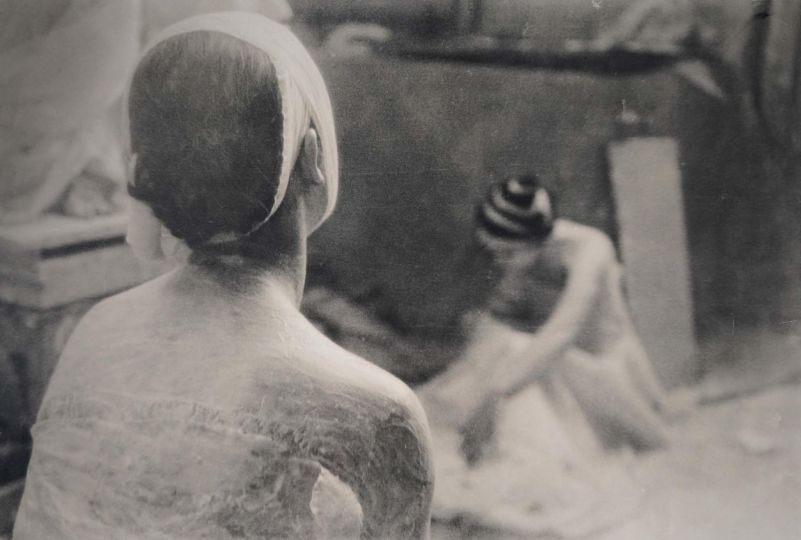

Pesin’s 1984 series refers to the famous novel by George Orwell and was in fact produced that year. It is a reportage of a correctional facility for juvenile delinquents. To be allowed to take photos there, the artist had to pretend he was applying for a job as a photographer at the institution. Later, during Perestroyka times, Pesin successfully exhibited this work in Moscow, but when he risked exhibiting it in Kharkiv, it was immediately confiscated. The next day the police arrived to search his darkroom, but with a friend photographer’s help early in the morning Pesin had managed to make copies of the 1984 negatives and had removed all potentially incriminating prints and films.

The beginning of the 1990s, economically and artistically a most challenging time in Soviet and post-Soviet history, saw the group’s slow, but inevitable disintegration. Some group members continued to make art, some moved to the West, some chose other careers. Had it not been for the state collapse and the economic hardships that followed it, Gosprom may have seen a brighter artistic future, for instance, directing the group aesthetics into conceptual art approaches.

Oleksandra Osadcha, a researcher for the MOKSOP, supports this idea:

“The works of Gosprom artists, Igor Manko’s and Vladimir Starko’s in particular, in some aspects perceptibly follow the pattern of photographic practices as part of conceptual art outlined by Jeff Wall. Their features — deliberate randomness, uneventfulness, and indiscriminate choice of subject matter, intentional amateurish quality as opposed to artfulness — are emphasized by routine repetitiveness of motifs and a tendency to serial representation. In one of his polyptychs, Seascape with a Borderguard Helicopter (1990), Igor Manko literally quotes a conceptualist technique of reduction of the object by marking it with an arrow pointing at a dot on the horizon.”

The work was made one year before the USSR collapsed, in Jurmala, Latvia. The helicopter was in fact patrolling the Soviet border in the Baltic Sea, thus marking where the Iron Curtain must have hung.

Igor Manko

The artists associated with the Gosprom group and their 1990’s careers:

Sergei Bratkov — ran the Up/Down Gallery in the 1990s, then moved to Moscow, where he teaches at the Rodchenko School.

Igor Manko — suspended his artistic activity in 1994—2004 to manage a language school.

Guennadi Maslov — moved to the US in 1993. Photographer and Professor of Photography at the University of Cincinnati, Blue Ash.

Konstantin Melnik — abandoned photography by the mid-1990s.

Misha Pedan — moved to Sweden in the early 1990s. Photographer and curator. Teaches at the Stockholm School of Photography.

Leonid Pesin — moved to Australia in the late 1990s.

Boris Redko — abandoned photography by the mid-1990s and switched to painting.

Vladimir Starko — abandoned photography by the mid-1990s.

To learn more about the Kharkiv School of Photography visit the platform Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics. The platform is a part of the Ukraine Everywhere program of the Ukrainian Institute and is dedicated to the promotion of the Kharkiv School of Photography achievements among the wider international audiences and its introduction to the all-European artistic context.

Igor Manko is a photographer from Kharkiv, Ukraine. He has been a member of the National Union of Fine Art Photographers of Ukraine since 1992. He holds a degree in linguistics and is the director of a language school. He exhibited his photographic works in Kharkiv, Kyiv, Moscow, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, and Denmark.