The inspiration behind the series Dulce y Salada by the Colombian photographer Jorge Panchoaga came from his flight over the Andes in 2011. Nested between two mountain ranges, a multitude of farm plots hug the serpentine trace of a former riverbed. Struck by the vision of this environmental change and its visual ambiguity, Panchoaga fell in love with water, as vast as the subject may be.

Trained as an anthropologist, Panchoaga began collecting all sorts of documentation—starting with physical samples, in the form of gallons of water drawn from various Colombian rivers. Next came sound recordings of water in all its forms—brooks, drops, streams, and waterfalls crashing at many decibels—as well as interviews with individuals from different social backgrounds.

A member of the Nasa people (also known as Paéz or Cauca), an indigenous nation originating in the southwestern highlands of Colombia, which is also the home region of the photographer, offered the most poignant answer to the question: “what does water represent from both a physical and a spiritual point of view?” Without hesitation he replied, “Water is more precious to us than gold.”

Sent to a laboratory for analysis, over twenty water samples that Panchoaga had carefully collected, mysteriously disappeared. Sound recordings, on the other hand, kept accumulating on his hard drive. The project remained on the back burner until the photographer was sent on an assignment to Nueva Venecia, a village floating in a vast marshland in the Magdalena River estuary, with stilted houses, a church, and scarce canoes. Fishing used to be the major source of income in this area until pollution and climate change intervened.

The water here is sometimes salty, sometimes fresh, due to the specific topography of Nueva Venecia, and in particular its proximity to the sea. This phenomenon, essential to the local fauna, is becoming increasingly rare, which in turn has drastically reduced the diversity of fish. “Sweet & salty” nevertheless became the title of this series of photographs, which are the fruit of multiple journeys and as many lines of research. Panchoaga’s notebooks, filled over the years with technical drawings, graphs, notes, references, and sketches of places, testify of his labor.

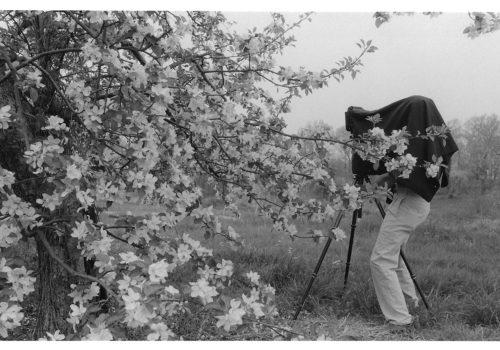

The stunning visual and poetic wealth of Dulce y Salada derives from the way in which the series was constructed in waves. While it began in color, it turned black and white when, on the eve of a journey, and once Panchoaga had saved enough money to buy supplies, color film had gone out of stock.

Initially conceived as a study of the precarious situation of fishermen, the series opens as a social inventory of the place. For that purpose, the photographer did a series of formal portraits imitating the style of old-fashioned studio photographers and using backdrops with suggestive motifs. The playfulness of the backgrounds reaches a climax with the magnificent portrait of a woman lying on a dried fish covered floor. “This is an inevitable cycle. Without water, there is no ice, and without ice, it’s impossible to transport fish,” noted Jorge Panchoaga.

Images of fish are, in turn, the object of a topographic gallery, resembling antique animal plates, and the black and white lines are so fine they look like drawings. The inventory is completed by a few pieces of trash found in the water: shoes, bottles, and other items. This addition is more than merely anecdotal: it foreshadows a turning point in the series.

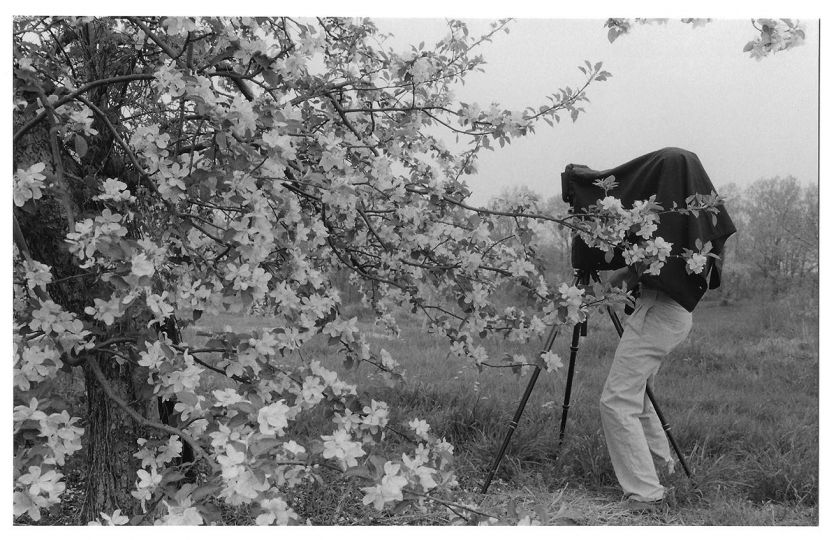

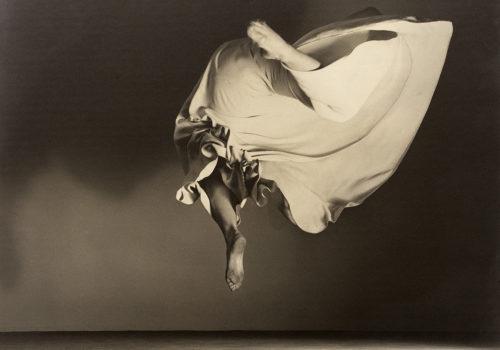

Little by little, the residents in the photographs begin to lose their limbs, appear only as torsos, a leg, a head barely visible above water, or clothing without their wearer. This approach is not merely a whim of style. It evokes the tragic story gathered over numerous afternoons spent talking while waiting in a hammock for the air to cool down enough to be able to breathe and work. Ponchoaga’s portrait of a fisherman, his head hooded with a t-shirt, is a stark illustration of the daily sultriness.

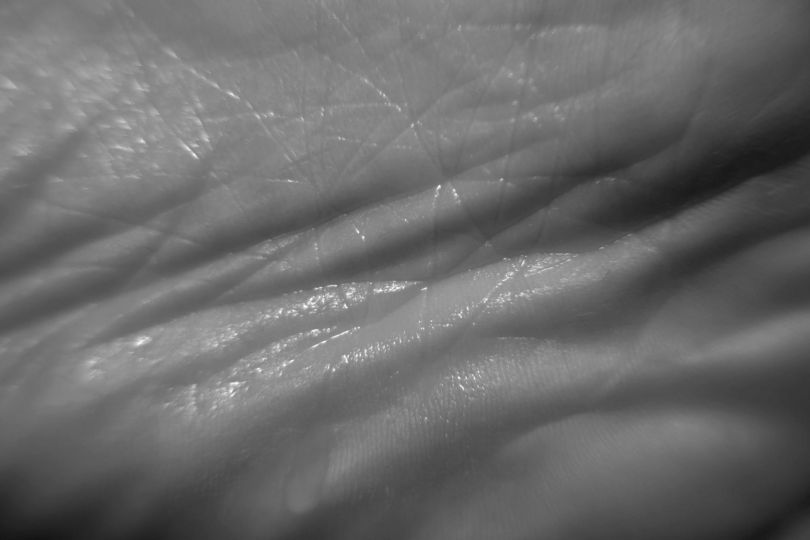

This beautiful story of people and their environment is tied to the story of the Colombian conflict. It represents a trauma in the lives of Nueva Venecia residents going back to a time when the Colombian paramilitary would throw their victims’ body parts into the water. This tragedy continues to haunt the inhabitants of the marshlands. The idea of memory inspired Jorge Panchoaga to represent the different states of water as a metaphor for memories that circulate, evaporate, or freeze. He thus trapped several fish in blocks of ice and then captured them on film. They look like the pupil of an eye that observes the unfolding of history, able to do nothing but bear witness.

Laurence Cornet