An entire generation of photographers has come of age since digital technology supplanted film technology in photography. For those who have never wound a roll of film through a camera or dipped their fingers in darkroom chemicals, but have nonetheless wondered about that archaic process, let me recommend the following description from photographer and former Life magazine director of photography John Loengard. It is as succinct and eloquent an account of photography’s origins and chemical past as you will ever find:

An Englishman named Henry Fox Talbot invented the negative in 1833. In the dark, he coated a sheet of paper with silver chloride. Putting a leaf on top, he left the paper in the sun. (Silver and chlorine combine in the dark to form silver chloride and separate when struck by light.) In the sunlight, chlorine gas floated off, as a gas would. Dark particles of silver embedded in the paper’s fiber appeared everywhere except in the leaf’s shape. The paper under the leaf stayed white. A wash in salt water took away the silver chloride that was not touched by light. The negative was born, and for more than 150 years, every black-and-white print was made from one.

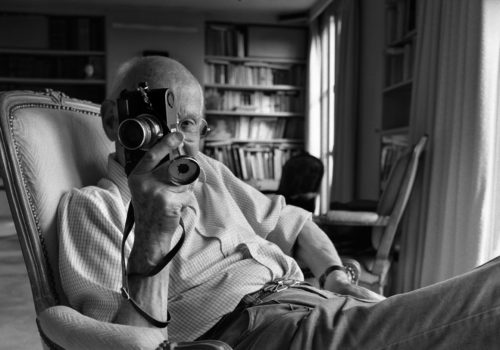

Loengard’s description of analog photography’s essential formula appears in the introduction of his new book Age of Silver: Encounters with Great Photographers (powerHouse Books). Loengard calls it “a personal tribute to silver and a few of those who made fabulous use of it,” which is an accurate representation, as far as it goes. The book brings together Loengard’s portraits of a number of photographers who made iconic images through the mid-to-late 20th century—a photographic Greatest Generation that he documented during the 1980s and early 1990s—along with his photos of some younger photographers just beginning to make their mark in the years before silver-based photography gave way to digital. Side by side with the portraits are Loengard’s pictures of the photographers’ famous images—not prints of the images, but the original negatives from which all prints are produced. Loengard presents them as objects of great beauty, illuminated by the glow of another photographic artifact, the light table.

It is the eighth book from Loengard, who began shooting photo assignments for Life magazine in 1956, while a senior at Harvard University. Later he became one of the magazine’s staff photographers, shooting much-admired portraits of artists (Georgia O’Keeffe), poets (Allen Ginsberg), and actors (Bill Cosby). After Life folded as a weekly in 1972, Loengard worked at the newly launched People magazine and later became director of photography for a monthly version of Life. In the 1990s, he took on the role of historian, researching and writing a number of books about Life, including The Great Life Photographers (Bulfinch, 2004), which remains the finest reference work on the subject.

Loengard is a man of inquisitive, thoughtful nature. In the book’s preface, Vanity Fair magazine’s editor for creative development, David Friend, recalls working with him at Life in the 1980s: “He was prone to mumbling, to muffled responses, to pauses that would trail off into Sphinx-like silences,” writes Friend, who at one point describes his former colleague as a cross between “a Theban seer and a photographic Bob Fosse.”

“That is quite a description,” I told Loengard recently, over coffee in the lobby of the Algonguin Hotel in Manhattan. “I’m not sure I’ve ever encountered a Theban seer before.”

“Oh, well….” mumbled Loengard, trailing off into Sphinx-like silence.

We were discussing the new book and some of the photographers featured in it—for instance, Henri Cartier-Bresson: “He was like a tea kettle that is always on simmer,” said Loengard. “If you said the wrong thing, all of a sudden he would start steaming.” And Harry Benson: “I arrived and he was fully clothed. I asked him what he would be doing if I weren’t here, and he said he’d be in bed all morning talking with people on the phone. So I asked him to get undressed and into bed.” And Berenice Abbott: “She was not impressed with being the subject of a photo story. She didn’t have much time—she gave me a couple of hours in the morning. She was having guests for dinner and invited me to stay, but I didn’t, and I’m sorry I didn’t.” Then there was Annie Leibovitz, who he shot in 1991 as she photographed a dancer while balancing atop one of the gargoyles on the 61st floor of New York City’s Chrysler Building. “She didn’t like the pictures she took up there,” said Loengard. “She preferred pictures she took in her studio that afternoon. Which proves that you don’t have to go out on a gargoyle to take a good picture.”

As we talked, our conversation turned in a number of directions, from the great photographers of the past to the shape and substance of photography today. While Loengard’s book can certainly be taken as a valuable historical document, it is more than a tribute to the past. By looking back at the bygone era of silver photography—a time when, as Loengard says, “everyone knew who the 15 best photographers in the world were”—it puts our modern, digitally democratized world of photography into context. Once, the visions of great photographers and the opinions of great photography editors defined the art; today, in a global photographic community with access to iPhones and the Internet, can we hope to find a consensus about what great photography is? Or is that notion just another vestige of the past? There may not be answers to those questions, at least not yet, but that doesn’t diminish the joy of hearing Loengard ponder the possibilities.

***

David Schonauer: John, let’s not start by talking about the age of silver—let’s start with the age of digital. How do you think the technology has changed photography?

John Loengard: Well, what I can tell you is that if I were starting out today—or if digital photography had been around in 1953, when I started taking pictures, I would never have taken black-and-white pictures. I can’t imagine why I would. I shot black and white because color film was just this hideous stuff—I’ve often thought that it was invented by a German physical therapist who straightened out peoples’ legs with steel and leather. With color film, you had to take pictures of things that looked good on color film, and a lot of things just didn’t look good on color film. But with digital, you use color the way we once used black and white—you just take pictures of things that interest you.

David Schonauer: Let’s get into that further. We’re talking about aesthetics here, not just technology.

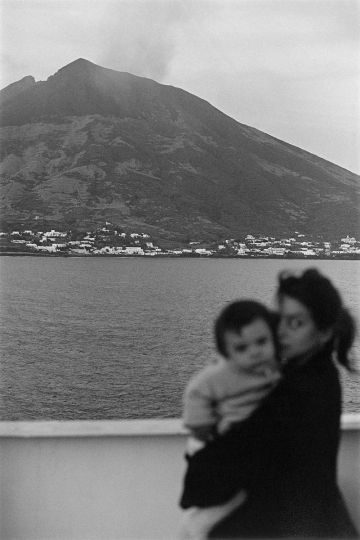

John Loengard: It was important that silver chemistry was the basis of photography for more than 150 years, and that for the first 100 of those years there was no real way to take pictures in color, until Kodachrome came along—and then it was only sort of possible. You had a century of black-and-white photographs, and its emphasis was on expression and gesture—if you wanted to photograph someone, say typically, in the act of living, you got a sense of who they were and what they were by how you depicted their body and the expression on their face. I think that’s one of the qualities of black-and-white photography that we became sensitive to. And this was something that color would not add to. If we had had digital color 150 years ago I think we would have been doing all that. But it might not have been as clearly refined as it is in black and white. But that being said, I don’t know why anyone would go and purposely take black-and-white pictures today. I think the new grey field is color.

David Schonauer: How did you get interested in photography?

John Loengard: I got interested in photography when I was 11—thought it was magic. By the time I was 14, I’d run out of subjects. You could take pictures of trees and buildings and people on the street, but then what? Then I discovered something. I was asked by somebody at my prep school newspaper to take a picture of the captain of the football team. I discovered that if you were from a newspaper you could walk out into the middle of the field and ask the football team captain to do whatever you wanted him to do. In my case it was asking him to punt the football, and he did. And so as far as I was concerned working that way increased the range of subjects that I had.

David Schonauer: Your identity as a journalist was important to you then.

John Loengard: If you’re a journalist you can go into other peoples’ lives. They understand why you’re there, and it’s not personal: It’s like being from the cable company—they’re happy to have you. They think that some publication has recognized their great value, and they’ll do pretty much whatever you want. It gives you a great deal of freedom, I find, to do it. Conversely I’ve always felt that I should never do what I think anybody expects me to do. If some publication asks me to go take some pictures, I immediately think of what that publication prints when it prints pictures of that subject, and I immediately think I will never do anything like that.

David Schonauer: Is that an idiosyncrasy of yours, or part of your professional outlook of what make good photography?

John Loengard: Well I think it’s what makes good photography. Otherwise you’re just going out and accomplishing what somebody else has done. That doesn’t seem to make any sense to me. I want to find something that surprises me. And the advantage of that is that if it surprises me and it works out, presumably it will surprise the reader.

David Schonauer: Surprise is a word that came up in David Friends’s introduction to your new book—he talks about how as a photo editor you pushed photographers to find spontaneity and surprise.

John Loengard: Yes, I was looking for pictures that inform the readers of something. Not just…that’s a good-looking picture, boy, that photographer knows how to take a good picture. I think pictures like that are incredibly boring. It’s fine for portfolios, it’s fine for gallery shows, I guess, if that’s what you want. But I think that to inform people, to have something to say to people, a photograph can’t be just well made.

David Schonauer: John, I remember talking with you once about Ruth Orkin’s famous picture of the American girl in Italy—where she is the center of attention of all the men in the square in Florence—and you talked about it being a “telling” picture.

John Loengard: I think “telling” is a good word for it, or for any picture that gives you some insight into a subject that you hadn’t had before. And it may be because it simply encapsulates an attitude. For instance, the Ruth Orkin picture you mentioned encapsulated an attitude of men and women so well that you keep looking at it and being fascinated by it. The fact that it’s a well-made photograph is not the point.

David Schonauer: Okay, we talked about what makes a good picture, and silver and digital photography. Let’s talk about your photography, and the pictures in the new book. You start the book with a photo you took when you were in college in 1953, when the king and queen of Greece were touring Boston. The point of the photo, in the context of this book, is that what you were really shooting were the press photographers who were there for the occasion.

John Loengard: I took the picture of press photographers waiting for the king and queen to come out of a meeting with the president of Harvard. Actually Lisa Larsen, the Life photographer who died very young, is cut off at the left. It was the only picture I ever shot of other photographers. And then I just didn’t photograph photographers again at all, until the 1980s.

David Schonauer: And then you started to focus on photographers. Why?

John Loengard: Photography, suddenly in the 1970s, became considered an art, and magazines started slowly to treat photography as an art and photographers as artists—Ansel Adams was on the cover of Time magazine in 1979. And in the 1980s and early 1990s I photographed a number of photographers because they had a new book, or because they were old enough to be finishing their careers and worthy enough to notice.

David Schonauer: There were photographers—especially Life photographers—who were well known before the 1970s. I’m thinking of Margaret Bourke-White.

John Loengard: Her pictures were well known, her name was well known, and there were a few pictures of her that appeared in editors’ notes and other places, but there was never any story on Bourke-White as a photographer, the way you might have had a story about Hemingway as a writer or Picasso as an artist.

David Schonauer: It’s interesting that photography achieved this new enhanced status in the years that followed the demise of the great picture magazines—Life as a weekly and Look as a bi-weekly.

John Loengard: I don’t think there’s a connection. I’ve got a very cynical view that it happened because in the1960s universities suddenly started teaching photography, and they did that because nobody could flunk photography. One of the benefits was that no male college student was likely to flunk photography at a time when there was a war in Vietnam and the draft had become a serious concern. There were other influences, of course, such as John Szarkowski’s intellectual ammunition at the Museum of Modern Art. Photography as an art wasn’t a completely alien notion. But until the 1960s and 1970s Harvard had not considered photography to be of any intellectual interest, expect in copying paintings. And suddenly Harvard and other colleges started having courses in photography.

David Schonauer: So in the 1980s you began taking pictures of photographers.

John Loengard: I think the first time I did it was for a Life story on photographers born in the 19th century. This was in 1981. Mostly I would do the pictures on assignment. In 1989, because it was the 150th anniversary of photography, I thought of doing a project of my own and photographing the whole photographic world—camera store salesmen, scientists, editors…you name it. I started to do it, but the project really didn’t go anywhere.

David Schonauer: Why was that?

John Loengard: The reason goes back to what I was saying earlier about the advantages of working on assignment. I always found that the time I spent photographing people was much richer when the subject—a photographer or whoever—had a reason to be photographed. When I was on assignment, the subject understood that some publication like Life, in its great wisdom, had recognized his or her importance. They would be really up for it, for showing themselves to me, to the extent that they could. There isn’t that kind energy coming from subjects when you’re just taking pictures for yourself.

David Schonauer: Let’s talk about the photographs you made and the way you have presented them in the book.

John Loengard: What I like about the book, among other things, is the variety in the pictures and in the way they appear sequentially. Some subjects are seen from far away, others close up; some pictures show a face, others don’t show a face; some show somebody engaged in an activity that has nothing to do with photography, and others are portraits of people whom I asked to sit in a chair while I took their picture. This variety is what you want to get in any picture story. It’s what you would want to try to get with any one of these people as the subject of a picture story. And I hope my enthusiasm for the subjects comes through. I spent 66 years taking pictures, and I’ve had photographers who were my idols, and I have had photographers who were colleagues, and I’ve edited the work of photographers, and I’ve hired photographers to take pictures. I’m just immersed in photography, and it’s a human occupation that I love. So I hope that’s the feeling that comes across.

David Schonauer: This idea of a variety of pictures—is that coming from your training at Life?

John Loengard: Well, yes, from Life, but also just from my own work. I spent about nine years just trying to learn for my own satisfaction how to take horizontal pictures of human faces, which are vertical. How can you cut the face in a way so that readers don’t feel that something is cut off? How do you take a portrait that doesn’t look like a portrait in which you sat somebody down and said, “Here, I’m going to take a picture of you now.”

David Schonauer: How do you do that?

John Loengard: When I was photographing Alfred Eisenstaedt, he wanted me to shoot him at the beach, and he was showing me tricks of how to take pictures by putting a stick on the ground and telling your subject to walk around it in a circle, and that every time they crossed the stick you were going to take their picture. It never worked very well for me. He told me I didn’t get his hips right, which was true. But it was obviously something he’d done. It’s a wonderful trick.

David Schonauer: There’s also a picture of Brassai that you took, very close up to his face, cropping out almost everything but the center of his face. And he’s making a funny gesture with his fingers around one eye, like he’s looking back at you. That was an interesting horizontal solution to a vertical face.

John Loengard: Sure, and the hands make it easier. He’s doing that because I’m focusing a lens very close to his face, a 65mm lens, and he just did the same thing as a joke. He had these big bulging eyes.

David Schonauer: It occurs to me that the period in which you were doing this, from the early 1980s through the mid 1990s, was also a period when this generation of photographers was…well, they weren’t going to be with us much longer.

John Loengard: You’re right, and I was interested in that aspect. By the way, there were plenty of photographers I would have liked to photograph but never did, for one reason or another.

In the book I list close to 200 people that were prominent during this period who I would have liked to photograph. And there are plenty of photographers who came up after this period that I was focusing on that I would have liked to photograph.

David Schonauer: The fact that you could sit down and come up with a who’s-who list of the most important photographers—we used to do that at a magazine I worked for, but we stopped after digital came in because the photography world had grown so amorphous.

John Loengard: There was a time, before photography got discovered and revered as art, that everybody knew who the good photographers were. The people who cared about photography and knew all the photographers knew who the good ones were. And you could rank them in order, and move the order around according to what they had shot most recently. There was unanimity—a consensus of their colleagues about who was really taking telling pictures. I’m not sure that there’s the same consensus today, or the same knowledge of what’s out there and who is good.

David Schonauer: It’s very hard to find a place where everybody sees the same work.

John Loengard: That’s true. Of course there are and always have been different schools of photography. Beaumont Newhall may have been the one who really established a basis for identifying all this in his history of photography. Some people might say that his history is outmoded, but his list of great photographers is really a surprisingly good list that has stood up. And the people that I’m describing, their reputations are as good today as they were when they were shooting.

David Schonauer: There’s a sense that this is a piece of photographic history that can’t be repeated.

John Loengard: I think the real thing about the book is that the switch to digital somehow—I don’t know if anyone really knows what it all means. I think digital is wonderful, but we don’t know what it means. Today, everybody can take wonderful pictures with their iPhones, and many do. But it’s a question whether they take telling pictures. That question is one that time will have to answer.

David Schonauer: Many of the pictures in the book are from a series you did showing photographers or archivists holding negatives of famous images.

John Loengard: I got interested in photographing negatives because there was not market for them among collectors.

David Schonauer: Not because you thought, wow, silver is on its way out…

John Loengard: No, no—silver was going strong when I took the pictures. I was interested in why collectors never went after negatives. The negative is the one original thing in silver photography—and that’s what collectors are all about, getting that one irreplaceable object, so it just seemed to me bonkers that negatives never became something that people wanted to collect. And then in 1994, just as I was ending the project, I suddenly realized that the improvement in digital photography was about to render silver an industrial artifact.

David Schonauer: An important part of the book, obviously, is that is serves as a historical document, and that leads me to your other career as the great historian of Life magazine photography.

John Loengard: Well that was by chance. The thing I never knew about photography, and still don’t, is what a photographer does in his or her spare time. Really. It takes a hundredth of a second to take a picture. Photography is amazingly quick. If I’m going to take your picture, I’ll meet you at 3:00 and be done by 4:30, and I’ll have something good, or not, in which case I’ll be coming back tomorrow. In the meantime, I have a whole day to kill. So that curiosity led me to want to look into the lives of photographers. Also, other people had suggested interviewing the Life photographers before they all disappeared, and that was just a good idea. The magazine’s editor-in-chief, Jason McManus, had a slush fund for projects like that, and he provided the money.

David Schonauer: You started your career as a photographer and then moved into editing. Why?

John Loengard: I always wanted and expected to be a picture editor. I wanted to be a picture editor, in the sense of working with other people’s pictures. I was always interested in what they did. Seeing what someone brings back from a photo assignment is like getting a first-run uncut film shown to you. And you’re also trying to match subjects to photographers, and trying to suggest to photographers things that might be done. I felt with young photographers that the key was to convince them in as few words as possible that we didn’t expect anything in particular from them. We were interested in what they wanted to do. And you could hear them almost as they thought to themselves, “Oh, I thought you’d want something else”—something that they’d already seen in the magazine. And you’d have to explain that that was the opposite of what you were looking for.

David Schonauer: Back to the photographers you photographed—many photographers rightly or wrongly have a reputation for being controlling, and I’m thinking in particular of Richard Avedon, who you shot at his studio in 1994.

John Loengard: He was very nice. I’d never met him before. I went over to his studio and he led me straight to this room, and it was just a terrific room, with this wall of clippings. This was for People magazine, and the timing was important. He had had a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and the reviews were very poor. Before the show opened, the only pictures of him that appeared in any magazines were self-portraits, so it was obvious to me that he was controlling all this. And then People magazine came to him after the opening, when the bad reviews had come in—one of the nice things about People was that it was happy to do a story about something two weeks after it happened—and at this point I think Avedon was willing to let the magazine send a photographer.

David Schonauer: You also have a funny story about shooting Roger Therond, the legendary editor-in-chief of Paris Match.

John Loengard: That was from 1989, when I thought I was going to document the world of photography. When I got to Roger’s office in Paris, he was sitting in a chair with a blank white wall behind him. Over in the corner out of the way was a board with a mosaic of Paris Match covers. When I came in he said, “Oh yes, you’re going to take pictures,” and he ran over and got the board and put it right behind him. I could have politely shot him dead. I thought the plain background was much better.

David Schonauer: Speaking of French people, you have some lovely photographs of Jacque Henri Lartigue.

John Loengard: I was always impressed that the three older photographers I photographed in France—Lartigue, Cartier-Bresson, and Brassai—were so much happier than the three I shot in America—Berenice Abbott, Eisenstaedt, and Andre Kertesz. It might have been a matter of personalities, or the fact that in France they were living in a place where streets were named after poets and artists.

David Schonauer: Tell me about Kertesz. You photographed him in 1981.

John Loengard: He was a very hard subject. Sometimes the camera just bounces off someone. You just cannot take a picture that makes you feel like you really opened the subject up very much. Was it his personality? I don’t know. What surprised me was how bad his English was. And people joked that his French was worse. He was filled with self-pity, even in his late 80s, when he’d been world famous for many years. He would tell stories of his woes in the 1940s, when he found it difficult to get work. But at that time his English must have been much worse. He was probably almost incomprehensible then. That’s my interpretation at least for why he was rejected. He made it difficult for people in that sense.

David Schonauer: What about photographing photographers—are they hard subjects because they understand what you’re doing?

John Loengard: No. In fact I think they’re easier because they aren’t often photographed. It’s much harder to do a politician and to get something you haven’t seen a thousand times. Go do something on Mitt Romney these days…lots of luck.

Age of Silver, John Loengard

Preface by David Friend

Photography / Art History / Portraiture

Hardcover

9.8 x 12.5 inches

136 Pages

200 duotone photographs

ISBN: 978-1-57687-587-2

$45.00

$51.00 CAD