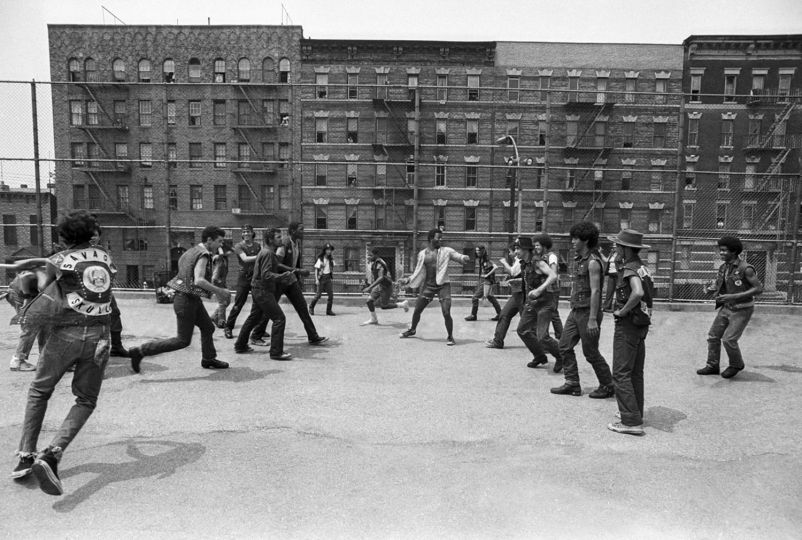

Among the many changes due to the strange compulsion that drives us to leave each decade behind like a reptile shedding its skin, the 1980s – or the myth that surrounds that era – stand out in the collective memory as the time when the accessory became the main thing: manifesting itself not only in the triumph of the bumbag and the bandana, the fluorescently brazen, the hardware store of rhinestone, fake and flashy jewels, but also in the transfiguration of the supermodels, who were suddenly propelled into the ranks of cultural icons – the shop window dummy supplanting the designer, the hanger the clothes. And in the celebration of that accessory, there was money – which took on a votive value in a society whose credo was that of the grocer (“I want my money!”), and whose impact and devastating effects we continue to see today.

The epiphany of the padded shoulder: a soft padding cushions predatory capitalism: blousy blouses, square backs, belted waistlines, “big” hair blow-dried to a bouffant shape, “mullet” haircuts, sticky lip gloss, headbands and sweatshirts. The focus of soft power, the power suit becomes a must-have, a suit for the woman who is sure of herself and her affairs. Montana and Mugler (and Gaultier for Madonna) are the designers of the day: they dream up a 1940s outline, from Flash Gordon B-movies, a science fiction steeped in a wholesome retro world. And paradoxically, in their desperate quest for the futuristic, they wind the clock back to a time before Dior, which had no sufficiently strong expression for the streamlined shapes of the war years, the exact opposite of the New Look.

While the presumptions of the designers set in motion during the previous decade continued, from the Japanese jungle of a Kenzo to the dazzling rise of Christian Lacroix (who through his intelligent use of colour and his cultural sophistication rounded off this period rather than expressing it), the true breakthrough no doubt came from the fashion houses (Comme des Garcons, Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake) that radically subverted the order of things by deconstructing the logic of the garment, yet whose subtlety will doubtless have left a more marked imprint on the history of fashion than our own imagination in those years.

They exuded a perfume of quiet vulgarity, which at the same time displayed a healthy indifference to all the rules of (good) taste and established hierarchies. Irony, scrambled codes, a postmodern mix of references and allusions, collages and samplings: perhaps we need to see in this freedom, as well as in the thirty years of cyclical changes that with regularity bring about swings in fashion cycles, the reason for the visible return to favour that the swaggering excesses of unbridled consumption enjoyed in the 2010s. Every cloud has a silver lining, and one would have concluded that this unabashed neo-capitalism was in full swing.

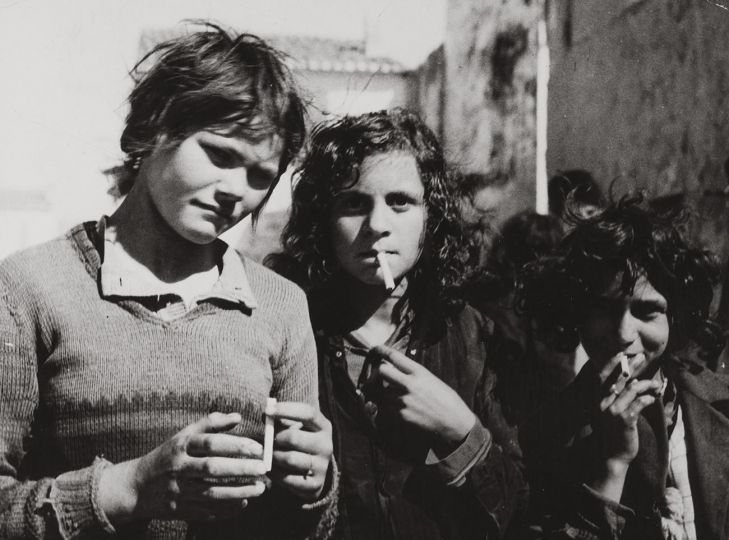

It is hardly surprising, then, that these were the years when Jean Loup Sieff launched his still-famous observation: “Basically, I think the role of a fashion photographer is not to show the clothes, which are mostly hideous, but to provide a service to the designers, ensuring that they can only be guessed at, and again…” A paradoxical profession of faith for someone for whom this activity formed one aspect of his work; but we should not really be surprised at this discord between, on the one hand, the master of black and white, of the carefully planned composition, of precisely calibrated light; and, on the other, the fashion for primary colours, cool dissonance, jubilant overexposure. … Nor is it surprising to see Sieff, in a note dating from May 1980, look back with affection to what retrospectively seemed the “right” time, his heyday, a perfect accord between the natural sophistication of the 1960s and his own sense of style (“It is nearly twenty years ago that I lived in New York, where I regularly worked for Harper’s Bazaar. We could still shoot fashion photography having fun and showing something other than boring dresses…”).

The 1980s, during which he turned fifty, are at the same time a period of unexpected renewal and of feverish activity in his own life: the birth of his two children (“strangely, now that I was in charge of two living beings and could no longer afford to be reckless, it was then that I found it again”), the publication of numerous books, a string of commissions which nevertheless allowed him creative freedom, travel to Shanghai, the Bahamas and the United States, and finally a retrospective at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris in 1986.

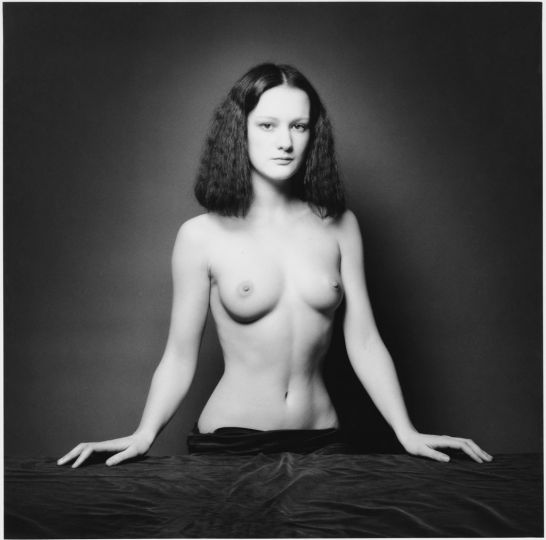

There was a sudden resurgence of the acute awareness of, if not constant obsession with, his own mortality. “It is strange”, he notes in passing, “how when we think of the inevitability of death, we say: ‘that’s life’.” He lists the friends who had passed away: Lartigue, Perec, Brassaï, Kertesz, “everyone who got off the train in which I am still travelling” … Dreaming of a life of leisure on the terrace of an outdoor café, as the artists of long ago would have been able to live, he sees it transformed into a funeral procession: “I am surrounded by future corpses, beautiful young corpses, unaware of their own precarious hold on life, thinking that they have eternity before them. For years I watched the pretty girls pass by on the street, wondering what their breasts were like, how copious their buttocks … today I often imagine them as skeletons. I look for the death’s head sleeping under their hair and waiting patiently for the moment when it will appear in the darkness of a tomb. All cemeteries are filled with long-legged passers-by who turned the heads of those sitting on the café terraces in the 1930s” (1 September 1989).

There is, however, nothing morbid about these musings, which seem to diverge from the subject of photography, and from fashion photography in particular; in fact, they are at the very heart of Sieff’s approach. Because for him photography is as much about the meaningful moment as about the poignant incident – which is why he was struck by Roland Barthes’ La Chambre Claire (1980, translated as Camera Lucida), in which he found similar thoughts about photography. “After many vagaries, transient certainties and dashed hopes, the photograph becomes for me again what it always should have been, indeed, what perhaps it always has been, the regret for the passing of time and the need to preserve and retain some of its moments” (1 November 1980).

Capturing the moment, a victory over chance, the miraculous equilibrium of a composition: this strong desire to “seize the moment and make it last” is, paradoxically, practised to perfection in fashion, the celebration of the passing of time. For just as High Fashion pretends to idealise the body (a tendency that can be seen in Sieff’s work for Alaïa and Saint-Laurent, in the context of those years), the photograph in turn must glorify this treasure box. Consciousness, the visceral impermanence of the body (this “wound with nine openings”, in the words of Cioran), is what justifies not the capture of the mess of the present but “the plastic quality, the organization of form, the roundness of light” … “I favour form,” he summarises, “because I see it almost as an end in itself. You can have the best of intentions, but these will be no use and remain incompetent efforts if they are not expressed clearly and with the greatest precision.”

Thus we can understand that, when faced with a decade whose quiet cynicism, confident excesses and playful riot speak to him only from afar, the photographer fails to express the spirit with his customary virtuosity, to outwit the limits of the present, pursuing the only quest that matters to him – that of “corporeal intelligence”.

Patrick Mauriès