Jeanloup Sieff (1933–2000) is considered one of the great French fashion and portrait photographers of the second half of the twentieth century. It is remarkable that, despite the number of books on his work, nothing has been published to date on his fashion photography. With this in mind, we set off to explore the archive of the Sieff Bequest. This monograph, with a selection of more than 140 works, provides a comprehensive and in-depth insight into Jeanloup Sieff’s career as a fashion photographer. The unique selection of photographs includes works from the early Sixties to the late Nineties and captures the photographer’s incomparable style in which elegance and humour, romance and melancholy, converge. A number of his iconic works are to be found as well as many photographs seldom or never published before.

Sieff’s first fashion photo was taken in 1952 with a friend as a model. The picture that can be seen in the shot was drawn by Sieff himself. His photographic career began shortly afterwards, in the mid Fifties, when he received a commission for the French fashion magazine Elle.

The Sixties, that period of change with its “youth revolution” and emerging pop culture, were intoxicating for Sieff as well. Photography and fashion were very much in tune with the times. Full of energy and aspiration, he moved to New York, a mecca for photgraphers at that time. With a few short breaks for commissions in Europe, he stayed there from 1961 until 1966, working primarily for Harper’s Bazaar, as well as for Show, Glamour, Esquire, Look and Life. These progressive, even avant gardistic magazines were breeding grounds for experimental and unbridled creative ideas and concepts. They exuded the rhythm and energy of the times by fusing the latest developments from the worlds of fashion, pop culture, art and music under the watchful eye of such legendary art directors as Marvin Israel at Harper´s Bazaar and Henry Wolfe at Show.

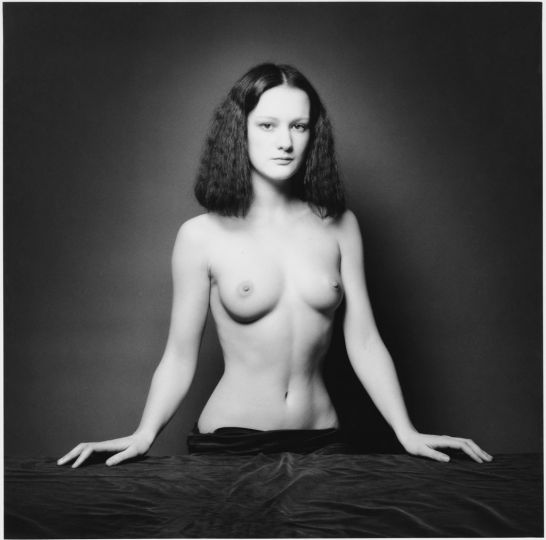

This thrilling and stimulating environment inspired Sieff to devise a new pictorial language and introduce new techniques – such as the wide-angle aesthetic – thus rebelling against the conventions of the Fifties. Models were now to look like real women instead of dolls or clothes-horses, and wear little make-up instead of having mask-like, expressionless faces: classic beauties made way for unusual and individual looks. The “it girls” of the era were Jean Shrimpton, Peneloppe Tree, Twiggy and Marisa Berenson. Sieff photographed them in such a way that – through eye contact – something of their essence could be perceived. In this way he succeeded in capturing the models’ personality and individuality and not just in drawing attention to his subjects.

“Jeanloup Sieff was passionate … typically French … He captures something of the women that nobody else does. Something like the Mona Lisa’s smile” (Gert Elfering).

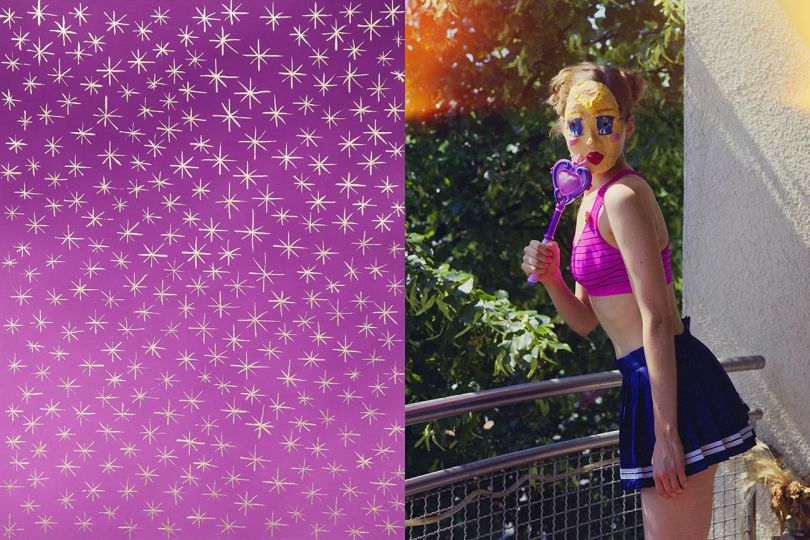

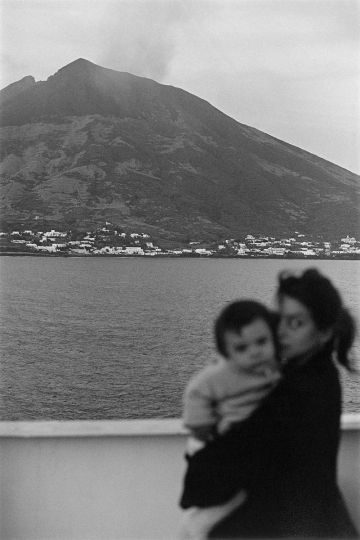

Inspired by the films of Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman, as well as by his work with dancers, Sieff succeeded in giving fashion photography a new importance. His miss en scène was experimental, surprising, witty and humorous: models were photographed in a studio against a monochrome backdrop so that the images could be used later in other situations as “pictures within a picture” – as for example in the photo in a birdcage (p. xxx). The urban space, modern as well as historic archiectural settings and the countryside became his place of work. “Leave the studio for the great outdoors” was his motto. Sieff captured André Courrèges’ cool, reduced “space girl” look – astronaut’s goggles and minimalistic, white spacesuits – in the equally minimalistic architectural setting of the Fondation Maeght. The space occupied by fashion itself in Sieff’s pictures is often very small. By using tiny, fashionably dressed figures set against the grand architecture of the World Fair in New York, Sieff tried to sharpen people’s awareness of fashion.

Time and again he incorporated press-like elements and backdrops to expand the narrative potential of fashion photography. In 1962, while working on a commission for Harper’s Bazaar, he visited Universal Studios in Hollywood, where he discovered the house perched on a hill that appears in Hitchcock’s legendary film Psycho. With the promise of beautiful models, Sieff tempted the film-maker himself to take part in a forty-five minute photo shoot. Following the photographer’s instructions, Hitchcock runs after the model Ina, gesticulating threateningly, as if intending to strangle her (p. xx). The result is a parody that can be seen as a homage to the famous Hitchcock film sequence. Classic cars, one of Sieff’s strong passions, also appear in his photographs as compositional elements. They sometimes form a projection screen, against which the glamorous and body-hugging fashions of the times were presented. The models’ expressions, the variety of different poses, and the often radical details that the photographer selected also appeared fresh and novel.

In 1966, Sieff was drawn back to the city where he was born, Paris. He received commissions from magazines such as Elle, French Vogue, Paris Match, Queen, Nova and Twen to add glamour to their products and layouts. He continued to encapsulate his very personal way of seeing things in his images. Shots such as Le dos d’Astrid and La robe trop étroite are evidence of this unmistakable style that impressively combines elegance, beauty and graphic clarity. They are an expression of his tireless effort to hold on to the fleeting beauty of a “time long past”, coupled with a tender melancholy.

Breathtakingly beautiful prints of Sieff’s virtuoso photographs, rich in tonality of the highest quality and with a presence of their very own, were exhibited in numerous galleries and museums. They can now be found in many museum collections including that of the Centre Pompidou, the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, and the Museum Ludwig in Cologne. In France, Sieff has the status of a hero of photography to whom the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris dedicated a major retrospective in 1986. He received awards such as the Prix Niépce (1959), was raised to the rank of Chevalier des Arts et Lettres in Paris (1981), and won the Grand Prix National de la Photographie (1992). In addition, he was also the author of a number of photography books.

The visual experience of his pictures has been made possible in a beautiful way with this publication. The introductory essays to each decade also provide an opportunity to find out more about fashion at that time and the corresponding zeitgeist.

We would like to thank everybody who has been involved with this publication. First and foremost, Sonia Sieff, who has accompanied this project with a great deal of passion and knowledge; the authors Philipp Garner, Patrick Mauriès, Franca Sozzani and Olivier Zahm for their informative contributions; and the archivist of the Bequest, Aude Raimbault, for her support pinpointing the prints.

In particular, we would like to thank Jeanloup Sieff’s friend, Harri Peccinotti, the former art director of Nova and the graphic designer of this publication, for his magnificent layout.

Our special thanks also go to the publishers La Martinière, in particular to Nathalie Bec and Marianne Lassandro, as well as to Prestel, where Curt Holtz and Gabriele Ebbecke embraced our project with enthusiasm from the very outset and oversaw its realisation expertly.

With this posthumous appraisal we hope to hone an awareness for Sieff’s idiosyncratic and independent position within the genre of fashion photography. His photographs are more than pictorial poems in which to immerse ourselves. Virtually no other fashion photographer of renown mirrors emotion, poetry and recollection mixed with fiction in his works in such a superb way as Sieff did throughout his life. An enigmatic aesthetic and pictorial language, which is still emulated in the pages of major fashion magazines to this day, unfolds before the viewer’s eyes.

May you be prepared and inspired to discover the invisible behind the obvious in his œuvre!

Ira Stehmann, Barbara Sieff and Sonia Sieff