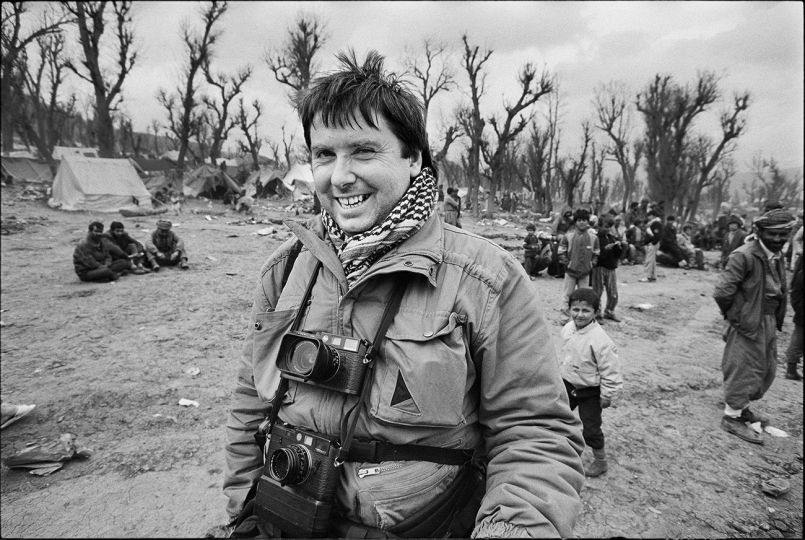

Everybody liked Tom Stoddart, even other photographers! Especially other photographers.

Tom was the photographer’s photographer.

His pictures from conflicts, catastrophes and humanitarian crises around the world spoke for themselves; with a compassionate eye and a click, Tom captured the moment that told the story. His pictures were technically brilliant, emotionally charged and worth at least the thousand words reporters wrote to accompany them.

His images from Sarajevo, the Berlin Wall, Iraq, Palestine, Sri Lanka and other global hotspots spoke of his courage and the suffering of those in intolerable situations and conditions. Driven to take that elusive picture to make a front page, he would later use the proceeds from highly paid advertising assignments to work for free for humanitarian organisations highlighting their campaigns usually involving children.

On news assignments, he preferred to work in black and white citing the Canadian photographer Ted Grant: “When you photograph people in colour, you photograph their clothes. But when you photograph people in black and white, you photograph their souls!”.

Born in Morpeth, Northumberland, to agricultural worker Thomas Stoddart and his wife Kathleen, Tom left school at 17 and applied for a job as a reporter on his local newspaper, the Berwick Advertiser where the only position going was for as an apprentice photographer. He took it and quickly discovered life with a camera was more exciting than one behind a typewriter. It was to be the start of an extraordinary career spanning five decades.

In the 1970s, Tom began working as a freelance in London’s Fleet Street, the then heart of the British national newspaper industry, and was one of the first to picture the teenage woman who would later become Diana, Princess of Wales. In 1998 over the Scottish town of Lockerbie Libyan terrorists blew up Pan-Am flight 103, Tom was one of the first on the scene. He had an uncanny nose for news, his ear always to the ground sounding out where to be next.

Photojournalist Derek Hudson, his friend of 35 years, recalls how he and Tom slept in a rental car while covering the humanitarian crisis in Isikveren, Turkey when Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guard persecuted the northern Kurdish diaspora in the aftermath of the first Gulf War.

“Tom was always the best company with his cool headed Geordie temperament and infectious laughter, which was just as well as we were about to call the tatty and cramped car our home for 10 days,” Derek said.

“If I had to choose anyone to sleep with in a tiny car, Tom was my man. A kinder more caring soul than Tom is hard to imagine. His talent only outshone by his largesse of heart. Bad mouthing folks wasn’t a thing with Tom. I taught him digital tech and he taught me to find good in everyone.” said Derek.

Tom’s work in Sarajevo, where he was badly injured, during the Bosnian war was among his finest of which thee 1993 image of Meliha Varešanović walking defiantly to work in pearls and heels while others ran to avoid snipers, remains the most iconic and one of Tom’s particular favourites.

“In 250th of a second, Meliha’s bravery, defiance, beauty and soul are captured and exposed in one powerful frame and for a photographer it doesn’t get any better than that,” he wrote.

“Ordinary women are capable of extraordinary things. When a crisis engulfs a community it’s the women who turn to face the challenges head on,” he said later in his book Extraordinary Women.

In a career punctuated with awards, not all his work was in war zones, catastrophes or crises. He photographed royals, prime ministers, world leaders and celebrities alike with charm and a touch of good humour delivered in a soft Geordie accent.

“You make great pictures with your head and your heart…and your feet,” he once said, a reference to the running required when being shot at.

But Tom was far more than a brilliant observer and portrayer of the human condition. He was a thoroughly decent man in a world that needs good men not just to shine a light into dark corners but to lead by example and encourage others to do the same.

“I have seen many awful things, but I have also seen a lot of fantastic and beautiful things,” he once said.

News of Tom’s death of cancer aged 67 came as a shock to many of his friends who had no idea he had been ill. Last year when Extraordinary Women was published to enthusiastic reviews and a major exhibition in his home city Newcastle upon Tyne, he was already ill and we did not know. This too was typical of Tom. He preferred to be the man behind the lens, not in front of it. He never sought to be the centre of attention.

The subsequent outpouring of sadness and tributes that have followed his death bear witness to that shock with dozens of messages from colleagues young photographers he befriended and mentored, the colleagues who worked with him and the friends who enjoyed a beer or three with Tom.

In 2015 Tom left his Docklands, London flat to move back to his native Newcastle. He had found the one thing he loved more than photography: Ailsa, his childhood sweetheart. In the blink of a shutter, he proposed, they married and settled in Ponteland a Newcastle leafy suburb where green-fingered Ailsa grew a magnificent rose garden while Tom nurtured his illustrious career making sure he always caught the last train home.

As one friend wrote on learning of his passing: “The world just got a bit smaller”.

He is survived by his wife Ailsa and his sister, Alicia.

Kim Willsher, Paris correspondent of the Guardian

Tom Stoddart’s photographs are courtesy of Getty Images.