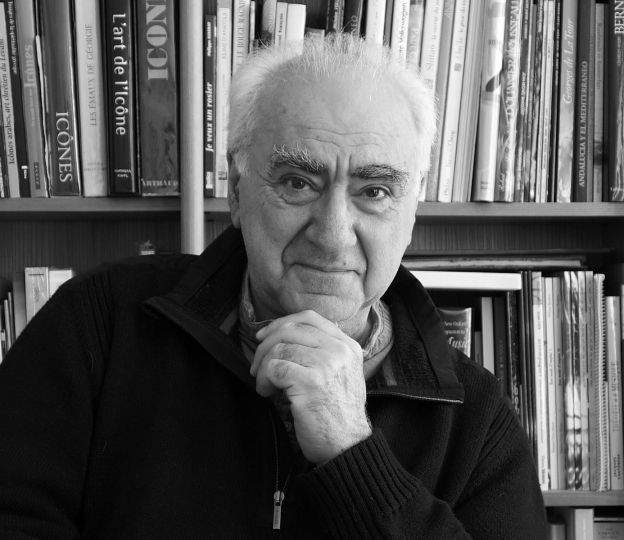

George Zimbel, photographer of stars and the ordinary by Jean-François Nadeau

Photographer George Zimbel died in Montreal at the age of 93. A longtime photographer in the United States, where he was born, Zimbel was known in particular for his famous photo of Marilyn Monroe in a white dress lifted by the air coming out of a subway air vent. The iconic shot was taken in 1954, during the filming of the film The Seven Year Itch, by Billy Wilder.

This famous image is one of the most famous representations of the idol of American cinema. However, George Zimbel did not pay attention to it until very late, producing prints from 1976 only.

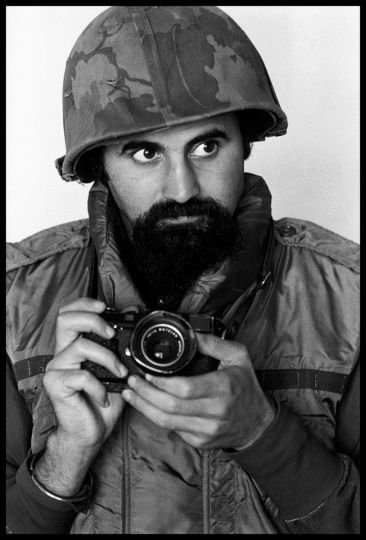

Most of his attention as a photographer was directed to interests other than celebrities, although he photographed plenty of them in 1950s and 1960s America.

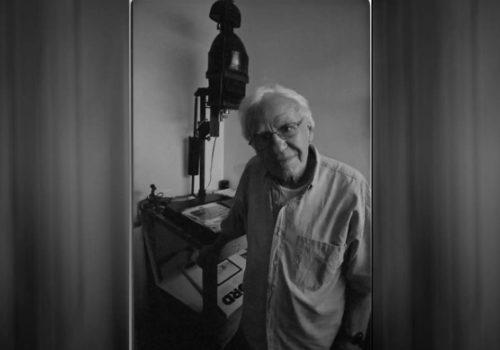

At over 80, he still cycled to his studio on Saint-Joseph Boulevard in Montreal to work there. On the white walls of the small office which adjoined his darkroom, just as in the corridor which led to it, one found here and there photographs of Marilyn Monroe, of John F. Kennedy, of Jacqueline Kennedy, of Harry Truman, of the Queen Elizabeth II or Pierre Elliott Trudeau. These familiar faces were, however, largely supplanted by people from all walks of life, young and old, captured in a split second of their lives that, all things considered, said perhaps less about them than about the photographer. “He loved talking to people, meeting people, exchanging,” his son Andrew told Le Devoir. “He was talking to everyone.” George Zimbel spoke simply, with warmth. “I am a photographer who belongs to the “modern” era. I am first and foremost interested in people’s lives. Today, many photographers are rather “contemporary”: they apply themselves to photographing a chair, an object, the nothingness, the mundane. I don’t really understand this approach, even if I respect it. But for me, it’s the human that interests me.”

Born in Massachusetts into a family of Jewish immigrants, he then settled for his professional life in New York, George Zimbel shared the friendship of some of the best photographers of his time. “We were all doing documentary photography, nothing else. But everything was completely different between one and the other because the key to it all lies first in the personality of the photographer. We thought Garry Winogrand made fun of people a bit. Arnold Newman was fair, perfectly fair, you know? Me, I was rather the romantic of the lot…” Zimbel left the United States in the 1970s, after working for several magazines and newspapers, including the New York Times. His departure for Canada was partly a protest against the Vietnam War, he will say. After spending a few years in Prince Edward Island, he finally settled in Montreal in 1980.

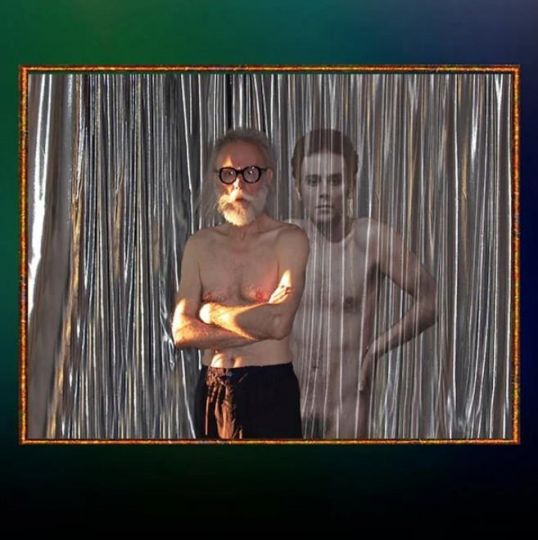

He felt a strong affection for black and white photography, in his sense closer to writing and the fragility of the human feelings he intended to communicate. “I have done color photography, but for me, everything is really better in black and white. I do not understand today this passion that people have for the hyperrealism produced by digital devices. That’s fine…provided that’s what you really want to do! It’s not for me. ” According to him, life was not at all as clear and defined as what the skilful juxtaposition of the pixels of the latest photographic sensors presents. To the point where he had long postponed the purchase of a small digital camera with German optics that he had taken to carrying around with him at the end of his life. After the death of his wife, which occurred in 2017, he had almost put aside photography, this second love of his life.

A humanist photographer George Zimbel was easy-going, simple and warm, which facilitated his relationship with his subjects. He was faithful to his habits, such as his frequentation of a small Asian restaurant where he was often found to chat during interviews, but also quite simply to discuss photography.

Zimbel belonged to the family of humanist photographers born out of the social experience of the immediate post-war period. He went to photograph in public libraries, in train stations, in the street. “I was very lucky to photograph all of this. Today, I would never be granted permission to photograph in libraries, schools or bookstores… No one can take pictures without getting bothered anymore! […] We do not have the right, it seems, to photograph on an individual basis, even when we are a photographer like me. But the police can do it! A store can film you! The City can watch you with surveillance cameras! That is possible! This is a ridiculous concept. A whole part of our visual history is lost because of this nonsense.” In a documentary broadcast in 2016, George Zimbel noted that “we live in a curious time”. “On the one hand, power prohibits photographers from doing their job – it is no longer easy, for example, to take a picture in the street – while later appropriating it very willingly. This same power is also authorized to place surveillance cameras everywhere.”We have never been so spied on thanks to the multiplication of images, while real photographers are struggling more and more to work, despite their sharp eyes and their ability to document our shared history.

Most of George Zimbel’s work is in black and white. He always worked with the same type of film, loaded in the same two old Leicas, although he liked, at the end of his life, a digital equivalent.

Even in old age, George Zimbel continued to go to his studio, where he took care of his thousands of negatives while listening to music. He made his prints himself using old enlargers saved from a fire that one day destroyed his studio. He used photosensitive papers which have become rare since the digital revolution. He died peacefully on January 9 in Montreal while listening to Glenn Gould play Bach.

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts devoted an exhibition to him in 2015. Prints of George Zimbel’s photos now belong to some of the major museum establishments, including MoMA and the International Center of Photography, in New York. , as well as the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Montreal, the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. Several collectors have also acquired some of his precious prints over the years.

Jean-Francois Nadeau

First published in Le Devoir www.ledevoir.com