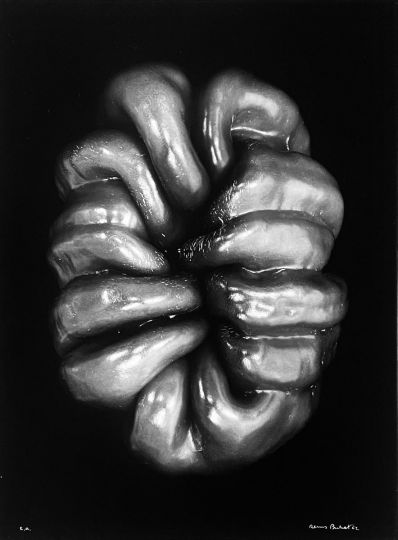

The view is broad, sweeping. The space, at once immense and bounded and goes from white to deepest black, the entire spectrum of greys is present, inscribing the materials in the implacable structure of the vanishing lines. On the right, the triangle of the sea wall matches that of the rocky surface on which the photographer is standing. Straight ahead, at the point where perspective draws the lines together, the lighthouse attracts the eye. The grey mass of sea and sky, thus outlined within the frame, is intruded into by a flight of birds, black because lit from behind. Like a negative.

This is Sète in winter. Sète in black and white, as Cédric Gerbehaye saw it. Sète as a discovery of terra incognita for someone who has accustomed us, rather, to distant lands – Palestine, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan – with ambitious projects that depict worlds in crisis, victims of their history. Sète as a return to Europe, and to roots; Sète as a break in the work he has been engaged on back home in Belgium for the first time, having spent so long elsewhere.

Sète – like all Gerbehaye’s previous subjects – is closely and precisely framed, as with a scalpel; or so one might say, were it not for the risk of giving the impression that there is something cold here, and dry. The formidable acuity of the eye is in effect qualified by the vibrations of the winter light, which reveals without exulting, and modulates without caressing. No small talk, verbiage, vapidity; no temptation to narrate, or to explicate. No road map. In other words, the opposite of major projects based on long investigations of socio-political issues, and the way history traverses the present. No, it’s a question of measuring, seeing, making visible what has been observed, encountered, seen. Hoping that rigour will impose coherence on it all. Documenting in the true sense of the term, both accepting the impossibility of being “objective”, or exhaustive, and affirming a wish to confront someone unknown.

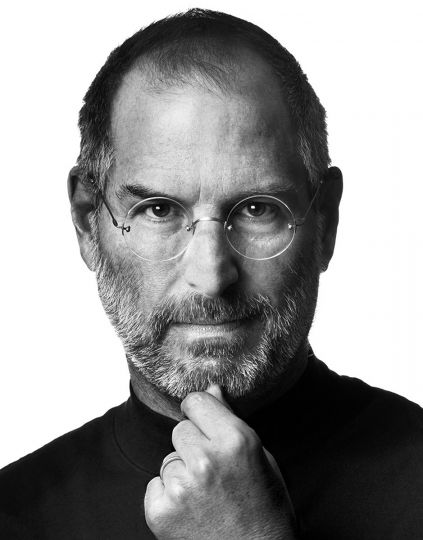

Strict portraits: those who stand in verticality like pillars along a route which, starting out in the direction of fishing and immigration, still awaits images. Because these are frank and direct, accepting the wager of proximity, forcing a confrontation that is as direct as it is devoid of animosity, exercising restraint as a mode of respect. Maintaining distance and letting the eye pass on, sustaining it close up, accepting it in the impeccable rectangle without disturbing or being disturbed; passing no judgement and indulging in no psychological readings or romanticism. Continuing to document: such is the intent.

Strangely, these portraits disclose, still more clearly than the “live” images, the significance of the whole, and the approach, where the crux of the matter lies. There is no question of dissimulating the photographer’s position, in any sense of the term. Introduced into a world of which he is ignorant, and which he is resolved not to disrupt. He keeps to his place, respectful, finally modest, not enticing us into interpretation. He refers us directly to the observation, not of reality but of its formalisation. And because he is in charge, because it is he who chooses the moments and the people, what he proposes is not that we adhere to his vision of Sète, but that we question it. That we do, in sum, as he did when he went towards discovery.

Sète in winter, in black and white, looked at the most accurately possible, is naturally the opposite of the clichés: a quest for sunshine, postcards, colour, excess of the Mediterranean. The sea is as grey as the sky; and the birds, in becoming images, have taken on a blackish tint. Time is strangely heavy, and seems to have difficulty in passing. It stagnates in durations impossible to determine, in territories that allow the sea to appear in them, but not to spread across them. Without really hurting, Sète in winter is problematic, like a breakdown.

Perhaps Sète is hibernating. And those who live there seem to be on their own. Isolated. Even the dog and the cat are alone. Is this because the space, in the port and along the shore, and even on the canal, along which a solitary boat is gliding, is structured around the only lines that brighten or darken what comes down from the zenith, filtered by sky? Sète – more singular and enigmatic than ever, because we never, finally, want to see it or look at it in winter. But Sète, amazingly strong on its axes, with lines that capture the eye, right up to the point where a wall or a shuddering facade forbid to discover furtherThe Rio Cinéma, frontally framed, is closed,and is no more than the aesthetic memory of another time. A stooped old lady walks past a sign proclaiming “Self-service solidarity”. No doubt she’s returning from the shops. No doubt she’s going home. Alone.

Christian Caujolle

Cédric Gerbehaye: Sète #3

Festival Image Singulières

8 – 26 May, 2013

Chapelle du Quartier Haut

Sète

France