Speakers

Stéphane Curtelin – Huawei

Pauline Sain – Magnum Photos

Michel Poivert – moderator

Diana Markosian – photographer

Her interpreter

Pierre-François Le Louët – NellyRodi

Antoine D’Agata – photographer

___

STEPHANE CURTELIN: Good evening to all, we’ll let the newcomers quietly sit down. We are delighted to meet you in this prestigious place , the Jeu de Paume and to see that the room is full. In addition, we are almost on time. As we are mainly French people, I guess it’s a good performance! I am Stéphane Curtelin, Marketing Director of Huawei in France. I will take your attention for a few minutes before giving the floor to our brilliant guests.

First of all, why this photo? We are lucky to have a pretty good video projector to appreciate the quality of the photos. Why this photo? Because it’s the winner of the 2018 Huawei Next-Image Awards. In a nutshell, it’s an idea of the company to showcase photography of today and tomorrow. To put it simply, to play a part – modestly – in the history of photography. There were photographers in the 1900s and even in the late 1800s who took picture with a tripod, chemical flash in hand, under a veil. And then, there was the famous image of Robert Capa in 1936 where, finally, we could catch the action. And, with Magnum who accompanies us tonight, this kind of photography capturing the action has clearly changed the history of photography. Now it seems to us that there has been a new revolution in progress for several years and, modestly, Huawei wants to participate by stimulating creativity around modern photography, of today and tomorrow.

However, it was necessary to create a framework that would stimulate this creativity: it is the Huawei Next-Image program, which comes in several parts. There is notably this World Prize. It was also necessary to give tools to the expert and amateur photographers by innovating, producing smartphones that constantly push the limits of photography for this superb little product that we all have now in our hands and from which we expect more every day. Huawei Next-Image is an annual trophy. We are going to introduce the juries of the next 2019 edition. As you can see, we are trying to surround ourselves with brilliant people who have an authoritative view of the history of photography. There are people from Magnum, Huawei, artists, real photographers known and recognized for this grand prize to be open to the world. We have participants from all over the world. Last year, the winner was a Pole. The year before, there was a Chilean mother. We hope that there will be French winners this year. There are several categories. This was the 2nd prize in the Portrait category. This allows me to finish by explaining that Huawei Next-Image is a World Award, but it is also the Next Image Colleges, online and offline. Which I invite you to visit. There are photography classes, through the site, as well as meetings. And, finally, the Next-Image Masterclass. This is happening today, in partnership with Magnum, Leica Gallery, the Shanghai Photography Center and National Geographic. And I hand over to Pauline Sain, General Manager of Magnum, whom I thank in passing for organizing with us this beautiful event.

PAULINE SAIN: Good evening everyone, thank you for being here. I am Pauline, General Manager of Magnum Photos Paris office. I really wanted to thank Huawei for this opportunity. They trusted us. They especially let the photographers completely free to choose their subject and express themselves with the phone so thank you for this opportunity. I also thank our speakers, Antoine D’Agata and Diana Markosian, photographers of the agency, Pierre-François Le Louët from NellyRodi and Michel Poivert, Professor at the Sorbonne, who graces us with leading this debate tonight and to whom I will leave the floor. Thank you all.

MICHEL POIVERT: Thank you, good evening everyone, I am delighted to meet you here at the Jeu de Paume to talk with two photographers, but also with a collector, or rather I prefer to say, a photography lover, who will have every opportunity to intervene anytime he wants. Our meeting has also, I hope, a spontaneous, on the spot dimension.

The evening will unfold as follows: you will discover for the first time the new works of Antoine and Diana, which were made in record time as a photographic experiment with Huawei material, but they are mostly works who, we are going to see it, take a natural part in the pursuit of their singular work. When I was offered to speak with Diana and Antoine, there was a desire to talk about a theme that is both an important theme and affects the both of them. The question of self-representation, the question – perhaps a little classical – of self-portrait but also the question of intimacy appeared to be a rather obvious connector between their works and we therefore decided to articulate the presentation of their productions around these important questions.

Diana Markosian, you entered Magnum in 2016. You’re a new face in this famous agency. Your photographic work has been published in major magazines for a few years now, but most importantly, your work is digging a deep furrow between the intimacy of your family history and the History of Armenian destiny and society. This moment in your work where personal history and History intersect is completely part of the dynamics of your work. We will question these elements, see where you are in this work and how the it unfolds. We will talk about it with the pictures later.

It is difficult to introduce Antoine D’Agata in a few words. He has been producing books and exhibitions since the 80s. Antoine, you entered Magnum in 2004, if I remember correctly. Your work is widely distributed, as I said, through books and exhibitions. It gradually deepens an attempt to exhaust both photography and yourself in various and varied forms. True varied forms since those who follow your production have been able to see your extraordinarily different plastic proposals and I think that tonight we will both find works of Antoine as we know them through certain processes but also of things that are ways to jostle, to disturb the lines.

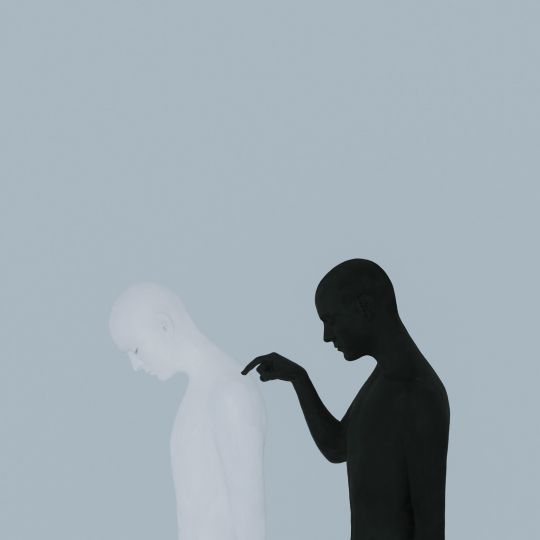

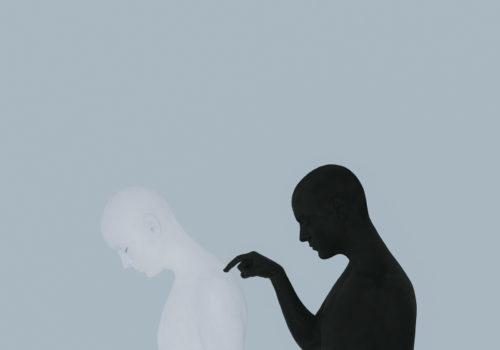

I suggest we start to look at some pictures. We will discover them together. That’s it, this image is from Diana. One thing connects you both in the conduct of your work: the practice of photography and film. We may have the opportunity to come back to it. Diana, when you produced these images, you made them, I think, in a very precise link to the project of the film. Could you give us some elements to understand these images that you are showing us tonight?

DIANA MARKOSIAN: I think I’m the only one who does not speak French tonight. This project of photos you see there was taken within a day. I had been working for two years on a project of reconstruction of my family. All these individuals you see on the screen are actors with whom I have been working on this project for two years. These two, in particular, play my role and that of my mother. It shows the life we left behind in Armenia to go to America, inspired by the soap opera “Santa Barbara” that we used to watch. When I was commissioned to photograph this, the idea was to have some time to create images around different sets and scenes that we had created for the film, but the phone arrived on the last day of the shooting. So, I simultaneously directed actors and the team, I photographed for my book and I created these images. They do not represent the project, but they are a glimpse of it. As you said, it’s an intimate look at actors who are no longer actors but an integral part of my family and have walked in the footsteps of my own family for two years. I do not see the relationship as a distant experience anymore.

MICHEL POIVERT: We were talking earlier about the possibilities of recording snapshots, life on the spot. Here, precisely, one has the impression that the question of the spontaneity is put in tension with the question of the pose. How do you work this tension?

DIANA MARKOSIAN: For me, everything is based on trust. I trust the subjects. I do not consider them as subjects, not even actors, but really as members of my family. They know their role perfectly. When I’m filming, I don’t refer to the actress who plays the role of my mother by her name, I call her by the name of my mother, and I call her “dear mom” for two years now that I’ve known her. There is so much trust. It is about spontaneity. I set up the scene and I give her enough context information so that she knows that every morning she has to go down nine floors with buckets, take the water and bring the water back. And that is enough for her to understand exactly what her head space needs to be. But that did not happen overnight. It took me a year and three months to find these actors. For me, it was not just about choosing a body, but choosing the right woman, the right children and the right father to take this journey with me because there is a responsibility from both of our ends.

MICHEL POIVERT: We understand that these images are the result of a long projection of your imagination. The question I ask myself when I see them is that of the reciprocity of feelings. You project yourself into this family but how do they respond to this affect? Have they also become your family?

DIANA MARKOSIAN: I think I have normalized everything that may seem very strange in this project. So, when I explain it, it does not seem strange to me, but I think that when I look from the outside or explain it, for example, to my grandmother, she thinks it’s a bit weird. When I told her the story of this reenactment, she told me “It was so hard to live at the time, why would you recreate it?”. The complete story is that we came to America when I was seven years old. My mother was a mail-order bride. A man chose her in a catalog, in an advertisement. They corresponded for six months then she took the plane, taking my brother and me with her. We arrived in America where she met this very old man at the airport. And this man lived in Santa Barbara. He became my father-in-law. I did not see my father for fifteen years and I ended up growing up in this city that we watched on television. So, I think that the actors respond in some way with the same energy that I gave. Once, we were driving in California and the actor who was playing my stepfather kept talking. I could not concentrate. I just said, “Dad, stop”, and the minute I said that, I thought “Oh my God, it’s not your father, he’s an actor.” So, I said, “Gene, I’m so sorry”. He told me “Kid, I wasn’t done talking!” I think we really feel energy from each other at this point. We have been together for two years.

MICHEL POIVERT: When I discovered your work, Diana, I was particularly sensitive to the work entitled “Inventing my father” in which you are working on a family album. I could not help but make the link between this autobiographical reconstruction work and the issue of the family album. Even before you make the film, didn’t you always think about making a family album? Aren’t these pictures of a family album, even an ideal one?

DIANA MARKOSIAN: I think that when we look at the images I created, we really feel that they were made in Armenia in 1996. I feel like I had the privilege of creating a time machine. I pressed the button and I went back twenty years. I really walked in the footsteps of my mother. With this project, there wasn’t ever the intention of creating a work on my family. It was really to try to understand the grey. When I started as a photographer, I just wanted to see the world, to live an interesting life. The California I grew up in seemed so small. I want to see the world and I was lucky enough to do it with my camera. When I met my father, everything changed with my work. It wasn’t about seeing the world, it was about learning to be by myself. The bottom line with this work is simply trying to really understand something that has affected my upbringing and then, hopefully, translate it to a broader audience. I do not think my intention was to create a family album. I did not think about ways to conceptualize that. I do not think about the outcome of my work, I just want to do it.

MICHEL POIVERT: Pierre-François Le Louët, are you receptive like me to the indistinction between memory, reality and its reconstruction in the images of Diana? How do you perceive them? What do you feel?

PIERRE-FRANCOIS LE LOUET: The position in which I am tonight is obviously a little uncomfortable and at the same time absolutely delicious. Obviously, the project is totally fascinating. This work is both extremely personal, but on a community that is the family, and the willingness to share it effectively with a much wider audience is extremely singular, intimate. And, at the same time, it resonates with all of us because it affects the childhood, the family. I also have a question for Diana on this desire to share this story that you tell us in different forms and with different mediums. This allows me to come back to the subject that fascinates me a and concerns us today: the mobile phone. Many of us use this mobile phone and especially image on the mobile phone as the way to share very personal projects with the greatest number. To use one more cliché, there are one billion Instagram users today, 95 million posts every day, extremely young people (40% of Instagram users are between 16 and 24 years old). The impact of these social networks, especially on the quality of the transmitted images and sometimes the success of the artists and the images themselves. For you, is the social network a dimension of sharing? Do you want to share your images on these networks or not?

DIANA MARKOSIAN: You’re asking this question at a specific point for me where I just said to myself for one month I need to get off Instagram. I’m already off Facebook but I need to get off Instagram. To be honest, I think it’s not the best influence. You can find inspiration, but you can also simply be influenced in a way that makes you forget why you’re doing it, why you’re even creating the work. I don’t think you’re creating the work to instantly get a like. You create to leave a legacy, to create something that lasts. When you do not get enough likes or if you are posting for an immediate result, you’re missing the point of actually making the work. For me, it can be a tool that’s very fun, but I think the version of me on Instagram is very different from the one I am in person. As long as these two people are not the same, I’d rather stay off.

MICHEL POIVERT: Thank you for this discussion. Now, we will look at the second part of the corpus with the work of Antoine. I noted in one of the many interviews that Antoine D’Agata was able to produce a quote that seemed to me in strong resonance with what is happening tonight and particularly the relationship to machines: “Photography is the language of action because it is immediate, conceived and accomplished in the moment, in the very heart of the gesture that generates it. And because it no longer requires, through contemporary technical improvements, other aptitudes than those to live, photography turns out to be the negation of an agreed idea that artists make today of their own word, passive, harmless and parasitic.” I raise the question of technical improvements that push photography to say even more what it is, at least in your practice. Can you tell us where these images were made in a few days, a few weeks ago?

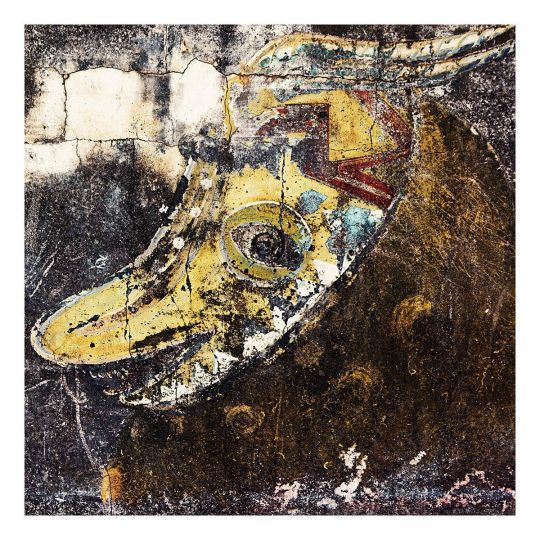

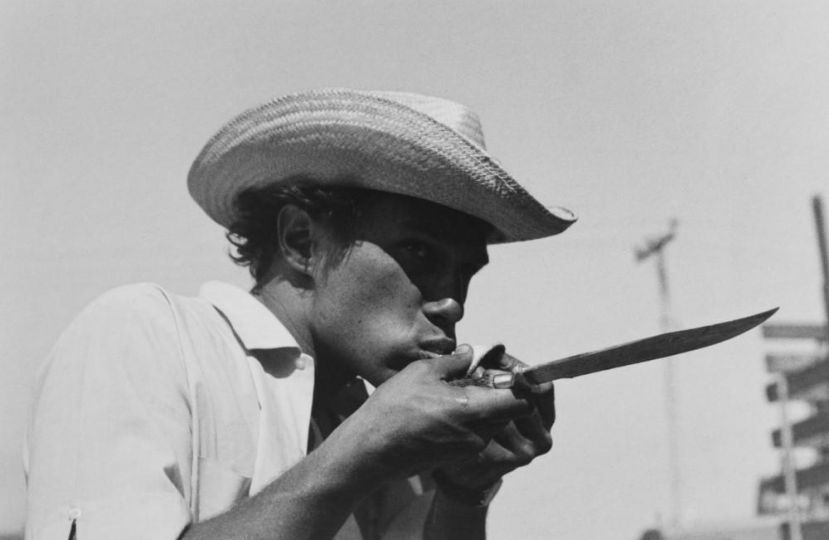

ANTOINE D’AGATA: They were made in six days in January. I went to Gaza for an NGO and was fired from there by Hamas because they googled my work. So, I found myself in Israel with little to do. I had been to Israel three times, each time in a conflict context. This time, there was nothing to photograph. This emptiness suits me, it corresponds to many things.

MICHEL POIVERT: There is a profusion of images. We are discovering it in grids. We know that your work can take this form, in a book, in an exhibition. There, we reach an attempt of exhaustion, even for the spectator to be able to read them. We are in allegories of the multiple, who speak so well of the subject in question. The wall, in this case, or other elements of our contemporary history. What is most in tune with our questioning today on the I in the photographic practice is that we imagine that the one who is exhausted is the one who was forced to conceive this banquet of images, these grids, these multiples. We cannot speak of a classic editing. We are in a building process. How can you imagine the work once all the shots have been taken? I believe that work can be the most exciting phase in this combinatory logic.

ANTOINE D’AGATA: There are many things. Before, in short, what I’m photographing here is the violence of the day. This is how I call the violence that is violent to me, economic and political. I photograph this violence in the coldest, most neutral and distant way possible. That’s what I’m doing here. To confront a thing to which one does not belong and to go to the end of this report of violence. It’s very different from what I do at night, to simplify, where there is a violence that belongs to me. Where images, characters, situations are unique. Here we are in a monstrous inventory of a certain religious, political reality, and that’s what I’ve been working on since last year. Another important point also to give context: from the beginning, from adolescence, I was always influenced by the situationist ideology. One of the lessons I learned is that of both responsibilities. The first one, which photographers generally do, is to look at the world, to criticize it, to understand it, to analyze it, to dissect it. I strive to do it as a photographer, there in particular. But there is another responsibility, at least as important, to generate a proper position in this context. This is where I try desperately to generate this position of exhaustion. This exhaustion is not gratuitous. It is to go to the end of this position which is mine.

MICHEL POIVERT: Here, the energy of the self is not necessarily in the iconography but in the practice. I think that we are all amazed to see, in the large grids in any case, this kind of power in the coordination of images. You are closer to the situationists than to the Oulipians, so we do not imagine you taking your rule of three and putting your images in the same line as an art of constraint à la Perec.

ANTOINE D’AGATA: I do not work alone on this. There is Gabriel, who is here today. I am unable to manipulate a computer. There is indeed a work of composition, of reframing. The function of language is unavoidable. It is necessary to bring the work towards this rigor, coldness. You speak of exhaustion. Abstraction means going beyond this possibility of reporting, of saying, of showing.

MICHEL POIVERT: For this violence of the day to be expressed in the work, there must be other days, that is to say the time of work. There is a time to film and then there is time to work. Doesn’t the violence of the night express itself, consume itself in the act, as we can see it with this work?

ANTOINE D’AGATA: That’s why I chose to show only pictures of the day. My problem in recent years is that my practice has become more radical. At night, I do fewer and fewer pictures. I’m less and less able to make images. Today, all night images are made by others when I am no longer able to make images. When I am beyond consciousness, beyond control. I strive to continue living as excessively, intensely and senselessly as possible. The images are made by people who are there, who accompany me, who have the strength and lucidity to make images.

PIERRE-FRANCOIS LE LOUET: In what we are seeing, this question of control is very present. At the same time in the subject, with questions of the maintenance of the spaces, the territories, the passage of the bodies, the authority of the circulations, but also in the formatting where there is a form of geometry.

ANTOINE D’AGATA: I worked a lot this year. I make so many images that I need time to format them. I am still working on images made last year in refugee camps, with migrants, about religion. In this work, everything that comes under my subjectivity of interpretation, of any poetry, of any style, bothers me. There is no objectivity, of course, but I am looking for the most neutral and cold thing possible. I try to neutralize as much as possible whatever would humanize the work in one way or another to report, in a way that is mine, of all this crushing violence. What I’m working on today is really this monstrous economic, political, religious violence. To report in my own way, I need to eliminate everything that alters, nuances.

MICHEL POIVERT: Pierre-François, keep speaking. You know Antoine’s work and probably also the parts where he dialogues with multiple images. What do you feel about it?

LE LOUET: First, I think your message really comes through. What is especially interesting in your words and in your work is that, in an extremely aesthetic world, you take a step against it at any price, whether day or night as you explained it, with extremely different shapes. Your very radical position is ultimately very rare in the world we know. It is extremely singular. You expressed this desire to go all the way. What is the end? When does it stop? Your images do not stop, you say it yourself. You are working on the images of last year, you haven’t had the time yet. This extreme research, what is its end?

ANTOINE D’AGATA: The end, we are all there. Photography interests me only in the sense that it helps me to confront this position that is political but also existential, these questions that we all share. This exhaustion, this emptiness. My photography is probably based on a deep atheism that makes this emptiness not just geographical or topographical, it is linked to existence itself. This desire for exhaustion, to go beyond one’s strength is the only way to live for me and photography just helps me structure this process.

PIERRE-FRANCOIS LE LOUET: You also have different ways of using and producing these images. We talked about film, camera, mobile phone. Is it important to have different tools?

ANTOINE D’AGATA: From experience, I have never managed to work by controlling things. I can only work by putting the danger in situation, whatever it may be, and having to react in the most instinctive, desperate possible way, to invent, to generate a technique, a new language. It’s not at all by doing what I can do. It is really having to react physically to a situation, whatever the context. Phone or not, this is not the subject. It was the urgency, the fact that there was not much to photograph, this exhaustion, it was long. The language comes from there. It does not come from an idea or a taste, a trend or a style. That’s what interests me because it forces me to live more, to be more, to feel more. Compared to the telephone, the fact of not having a device, it referred to this nakedness, this poverty. This kept me away from what scares me most, namely the professional side or the aesthetic / artistic side.

MICHEL POIVERT: I come back to the movie question. The film material, photographic but especially digital today, the film in the sense of the moving image. Looking at these grids, there are sequence effects that are created in the viewer’s eye. They are not very far from a form of chrono photography or flat film, they can even evoke the ancient contact sheets, this way of looking at the images contiguous to each other with movements. Diana and Antoine, you both film. And it turns out that the machines today are the same: that is to say we can film with a camera, a phone, lots of instruments. What makes you, one and the other, go towards the recorded image in motion, to put it in a simple way? When does the job need it, to expand in the long run?

ANTOINE D’AGATA: For me, it is barely touched, given the time. There is a series that is very important, but it is not very visible because it is taken from YouTube, images of CNN that become monstrous. In the photographic line, red photos are also made with the phone… This deconstruction of situations makes it possible to report situations in a more complex and different way, realities, some aberrations. The film interests me only to the extent that it makes it possible to report reality in another way.

MICHEL POIVERT: Diana, how do you feel the need to go to the movie or come back to photography?

DIANA MARKOSIAN: It depends on the project and if you feel like you have reached your own version of reality. The reason I wanted to create this as a moving image is because everything was inspired by a soap opera. It was for me to get as close to that. We had a script, we had the writers of “Santa Barbara” to write the story of my family coming to America. The idea of the video seemed very natural to me. If you remove that, I think that the images will be very one-dimensional, even without script, the soap opera. To be closer to reality, you must see it move and feel the weight of these scenes. In video, these scenes allow something that my own images could never quite do.

MICHEL POIVERT: If I asked the question a little backwards about the relationship between cinema and photography, it is because the film immerses us culturally, immediately and quite easily in the question of the fiction whereas photography will use more complex methods to make sure that you do not believe it, but that it is nevertheless photography. This relationship with the intimate, with oneself, with one’s history in your two works brings into play this dialogue between fiction and reality. For Diana, I find fascinating the reality of life experience, biography and history, and the need to make a fiction to join this reality. In what direction does it happen?

DIANA MARKOSIAN: I do not see the difference. I do not see it as reality or fiction. It’s just my interpretation of the story. It is very delicate because I understand that if I put all my family in one room, we would have a completely different reality from what happened that night. I am personally interested in my mother and her version. If I interview my father, my brother, or someone else, it will be a completely different story. For me, the idea of fiction and non-fiction does not matter. I want it to be what it is, and it has been its own journey because these actors interpret it in a totally different way. At some point, you have to let it go as a creator and let the people you trust absorb it and deliver their own version.

MICHEL POIVERT: Antoine, I turn to you. To draw a parallel between the works would be much too artificial but we try to weave echoes. If there is one characteristic of your work, it is to refound the value of the experience. Is there a space for the question of fiction in your world, with the nocturnal and the diurnal? Can fiction be a lever? How would it take you beyond the experience?

ANTOINE D’AGATA: As far as the night is concerned, there has always been a fundamental role of fiction and, in particular, of literature. Everything was based on that. I just finished a 4-hour film. It shows 23 women who speak about what they have lived, what we have lived. Above all, it makes their voices be heard. This film is made of different films, of three films that have been made over the years. Each time, I worked with a fictional script, always the same: “Madame Edwarda” by Georges Bataille. I have always tried to live up to the fiction. What interested me in the fiction is that it is more unreasonable than the reality we share. Living up to foolish, unacceptable, unachievable things allows you to play with your own life as a material. Except that you have to live these things. What interests me is to bring reality to the height of fiction.

MICHEL POIVERT: Pierre-François, as a specialist of our society as it goes or as it will go, you observe a lot the part of fiction in our lives and the relationship to art. Can art save us from the famous separation of the entertainment society by experimenting the works by ourselves?

PIERRE-FRANCOIS LE LOUET: Before answering your question, perhaps Antoine can enlighten us: does this intensity comfort you?

ANTOINE D’AGATA: No, it’s not the relief I’m looking for. I first seek to live this position as I can and then to report. What interests me is to report on a process. I will never do anything to relieve, improve or exit it. It is simply documenting the process of deterioration, of exhaustion.

PIERRE-FRANCOIS LE LOUET: This is perhaps the difference between the very singular approaches that you have witnessed tonight and what is the essence of many behaviors in society. This consumption of the social network, this search for the mise en abyme of a dreamed life focused on aesthetics, happiness, success, which are words that we obviously did not hear tonight. In this bulimia of images, in these series whose Instagram feeds drench us daily, there is obviously a standardization of taste that operates, extremely far from very personal artistic approaches like those we have witnessed tonight. We wonder a lot about the use made by society of this social network which we know today, where the like has become a new unit of value. I say horrible things, but I see it: the like has become a new unit of value, the brands choose the artists according to the number of likes they have, an image can be gauged with regard to the number of likes it has generated. We now know that there is a certain type of image that is more successful than others. The image of a face, for example, on Instagram will earn 35% more likes than another type of image. Saturated color images are more successful. There is a taste that emerges from the existence and growth of these social networks. This taste will in any case come to influence in a much more real sphere other experiences, and consumers that many of us are will have to face it. After all the horrible things that I have just told you, I am finally extremely reassured to see that there are fighters who resist somehow to these underlying tendencies and that there are still quite pure voices and very personal approaches.

MICHEL POIVERT: It amuses me to hear about purity but, indeed, as it often happens in the history of art, the artistic practice drains down and cleans the eyes, ears and bodies. When we have prepared this meeting, I had fun grafting the famous sentence “I is another” of Rimbaud. I is a photographic other. It is quite amazing to see that through the two works we observed quickly tonight, this question of autobiography, egotism, intimacy is constantly re-combined and is not a theme in itself but rather a form of self-practice that can be torn between biographical and historical, between day and night. Diana, is this film project going to be an experimental film or are you going, like “Santa Barbara”, towards a commercial project and a series?

DIANA MARKOSIAN: You will have to wait to see it! In short, I think it’s going to be very experimental. I started with a screenplay and then, two days before filming started last year, I put the script away. I told myself that I did not want there to be any sound. I just wanted to be in the experience of being there, to see what happens, to let the film be what it needed to be. As Antoine said, it’s about the process. The minute you stay with something scripted, you’re missing the actual art. The actual art is something you do not know. I had not thought of any of these images last year. They are the result of a process of errors and a lot of time spent with the casting.

MICHEL POIVERT: One last question and I will then give the floor to the public. Antoine, a film will be released soon about you, your practice, your work. It’s not a movie of you but about you. Is it an experience that goes beyond recording an interview? Can we name the author of this film and give the release date?

ANTOINE D’AGATA: I do not have the details. It’s always complicated. It is not the first time. Various documentary projects have been made about me. Each time, it was the same thing. Well, I am in no position to speak. It’s not my position to comment or give a perspective.

MICHEL POIVERT: We finally discover this I. It will be screened in a feature film. How do you contemplate it in the body of your work? Unless it is completely separate?

ANTOINE D’AGATA: Each time, I never allowed people to film the part that really belongs to me. What people are filming is the before, the after. There is an untouchable part, not watchable. Which is contradictory. I did not see the final version of this movie, but I saw the intermediate version and it’s happening around me. Mostly with people who know me.

MICHEL POIVERT: There are some pictures in the trailer where we see you set lights but that might be all. So, we will not have the behind-the-scenes of Antoine’s complete work?

ANTOINE D’AGATA: No. You spoke of this intimacy. For me, privacy is not a comfort zone. It’s a zone you invade, a combat zone. If you give this zone and this moment in pasture, whatever the logic, you spoil things.

QUESTION DU PUBLIC #1: Good evening. First of all, thank you for this event and this very interesting discussion. I have a question for Antoine. You spoke of research, of transcribing political, religious violence. Can we transcribe this violence objectively or is it necessarily subjective?

ANTOINE D’AGATA: I do not think I find myself in either word. All I can do is get as close to it as possible, not try to illustrate an idea. When we speak of the day and the night, these are antagonistic violences that merge into one violence with the violence of the world. In my opinion, we can only live this violence. I have always done everything I could to be neither a spectator nor a consumer. Of course, I understand it. There is plenty to say but that’s not to say that I want to. It is to share it in different ways according to the situations and, afterwards, to give an account of it. I think it’s a word in a sentence, it’s part of a larger logic. The main thing for me is to be there in these specific situations with these specific beings, as close as possible.

QUESTION DU PUBLIC #2: Diana, was the project done in California or Armenia?

DIANA MARKOSIAN: The project took place between the two countries. I traveled. I lived in California and that’s where I created the work and then I went back to Armenia. Initially, we tried to set the scene for my childhood home in California, but it did not really look like the former Soviet Union. So, we went back to the former Soviet Union and made the work there.

QUESTION DU PUBLIC #3: A photo reporter is there to capture the moment spontaneously. There is the accident that comes through the process of living. The accident is sometimes what gives ideas to the photographer. There is a limit of stage reality that many photographers cross when they stage a reality and, once it is staged, they let go and start to photograph compulsively. Is this process in your method or is it well thought out and limited to a singular point of view because there is a scenario? What is the share of accident and the share of scenario?

DIANA MARKOSIAN: For me, everything is a bit of an accident, even when I do come up with the room, the lighting and all the rest, it’s never what the image will look like. I just got film back today and I did not film what I needed. And then you start again because you are now working with a completely different set of images. Your vision did not come true, but something completely different happened. For the last ten years, it was never really staged, it was just an experiment. It is the gray. I like this gray area, and I try to embrace it. Otherwise, I’d be failing quite a bit because the result is not anything that I had in my head.

MICHEL POIVERT: The worse is yet to come. First, I thank you, thanks to the artists who agreed to play the game to come talk about their work in progress, thank you Diana, thank you Antoine. Thank you to everyone who helped participate in this evening. Thank you, Pierre-François, for this look at these works. The worst is yet to come, there is a cocktail and it is always a very difficult moment to live!

There is a book signing for those who wish to get closer to the artists. At 9 PM, we are lucky to have guided tours of the Jeu de Paume exhibitions. So, enjoy. Thank you for welcoming all the team and thank you to the Jeu de Paume. We gather now in a more informal way. I know that it is always in these cases that questions arise in the minds of those who have not yet formulated them. See you soon!

STEPHANE CURTELIN: I will add a few words. I was impressed by these discussions and this artistic production. We are delighted to have created this setting and gathering. I hope that you enjoyed it. If you did, we might be doing it again in September with other artists. Thanks again to Antoine D’Agata and Diana Markosian for playing along with our smartphones. Modestly, the smartphones contribute to this revolution, to this history of photography. The story continues. If you want to participate, whether you are expert, amateur or average photographers, the Next-Image contest will be announced on March 26, at the same time as the announcement of our future device. I hope that this one will serve again the cause of photography since, you will see, we have some nice surprises again with the P30. Thank you and let’s get together over a drink. See you soon!