The Houses of the Kassena

The Kassena are animists and live in the border region of Burkina Faso and Ghana. Holger Hoffmann visited them and is fascinated by the beauty of their houses.

When a Kassena woman dies, she is taken back to her parents’ house along the same route she took when she was married. During the marriage, she lives in her husband’s house. Here she gives birth to her children in the presence of all the wives of the head of family, symbolizing that it is the whole house that gives birth, and showing that the children belong to the house, not to the mother. The houses are built of clay. In the Kassena belief, the clay earth is the uterine regenerative source of life. The responsibility for the care and maintenance of the houses lies with the women.

The houses are grouped into a concession that in earlier times served as a fortress. The concession is an organic structure that evolves according to family changes, which explains both the newly added buildings and the decaying ruins, as well as the creation of numerous closed, semi-closed or open spaces that correspond to the multiple social and spiritual purposes. Because of this dynamic architecture, no two concessions are alike. According to their function, the houses have different shapes. The “Draa” are round with conical thatched roofs and reserved for bachelors, elderly men and soothsayers. In the rectangular “Mangolo” live the newly married. The “Dinian ” have the form of a lying eight and are destined for older couples and small children. They usually consist of three rooms: a kitchen, a bedroom and a reception room. These “mother” houses host the spirit of the ancestors. The grandmother, in particular, has the task of instructing her grandchildren in the customs and traditions of the ancestors.

The interior of a concession appears to the visitor like a veritable labyrinth of dark rooms. All domestic life takes place in them. Through a semicircular entrance about 50 cm high, always facing west, one enters smoky corridors that lead to the apartments of the various wives of the head of family. Each of the wives can live semi-autonomously in these chambers, which are equipped with a kitchen and bins for storing corn, sorghum and millet. In one corner, a shaft of light illuminates a millstone on which the housewife grinds the grain. Pots and calabashes are always carefully stacked near the fireplace and are an expression of wealth. The more a woman owns, the greater her prestige. In another alcove, there is an opening in the ceiling through which smoke can escape and which provides an exit to the roof terrace via a ladder. The women thus have access to a series of partitioned roofs where they dry corncobs and millet stalks. The roof terraces are also used for sleeping during the warmer months of the year and are accessible from the outside either by a staircase made of mud or a ladder carved from a tree trunk that forks at the end.

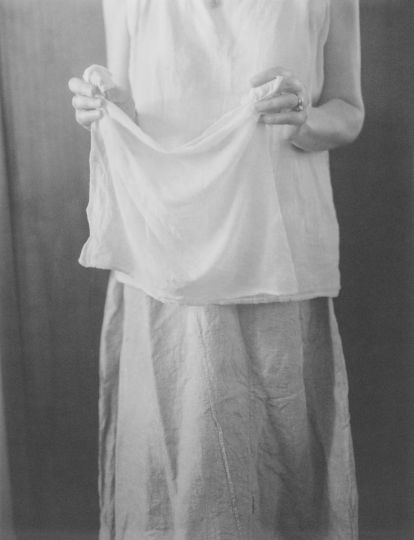

Every year around May, just before the beginning of the rainy season, the women together renew the wall decorations of their houses. The woman whose house is to be decorated calls other women to help. She has to feed the group and bring water, while the oldest woman leads the work and determines the decorations and motifs. The other women perform their tasks with a remarkable mastery and a perfect coordination. The organization of the work is demanding. In a single day, the wall surfaces must be prepared, the various fillers and paints made, the materials transported, applied, smoothed and the finishes applied, either by hand or with other specific tools, depending on the textures desired (pebbles, brooms, feathers, etc.). This knowledge, maintained and transmitted by the women, is a unique testimony of centuries-old practices that allow them to freely compose pattern friezes, each of which has its symbolic meaning.