Dominique Baqué’s recently-published study of the ever-paradoxical Helmut Newton takes us deep into his creative psyche.

Philippe Garner reports

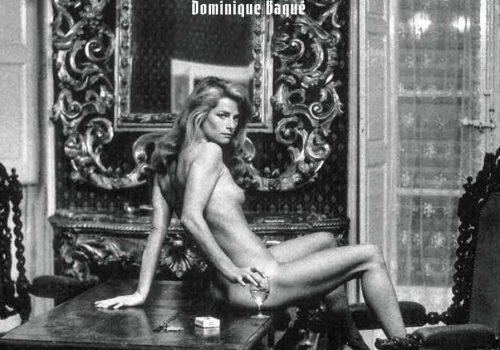

Helmut Newton died fifteen years ago. His work lives on and constitutes a remarkable cultural legacy – uniquely provocative, perverse, multi-layered, and wilfully ambiguous. Born in 1920, Newton was fascinated by photography since his teenage years; but it was not until he was in his forties that his images started to reveal a distinct vision, and not until he was in his early fifties that this vision matured fully into the complex, compelling, disquieting imagery that is the basis of his notoriety.

Dominique Baqué has published a book that explores with impressive acuity the darkest recesses of the creative psyche of this complex and in many ways seemingly contradictory character. Newton’s instinct as a personality and as an artist – a label he treated with caution but which he surely merits – was to maintain a teasing, dislocating sense of mystery. The cold, shocking, seductive, often morbid, always memorable pictures that he constructed were belied by the easy manner and considerable personal charm of their maker. He described himself as ‘a gun for hire’, a professional fulfilling commissions to make photographs for a substantial audience, reached mostly through the pages of magazines; yet he was driven by deep-rooted personal obsessions and invariably invested himself fully in every shoot to satisfy his own exacting creative determination as well as to meet the client’s expectations. Newton thrived on the attention he attracted and was always ready to be interviewed and quoted; yet he became adept at side-stepping questions he preferred not to answer and nimble at avoiding being put on the defensive by those who attacked what they found offensive in his work from the perspectives of their own agendas. The personality, like the images, as Baqué aptly suggests, was all the more intriguing for what was left unsaid.

Baqué has studied a very wide range of Newton’s images in her endeavour to find telling patterns in the clues they contain; she has, meanwhile, pieced together from published texts and from other, private sources a biography of his formative years and a very real sense of his psychology. She has notably benefitted from a dialogue with her publisher, José Alvarez, a very long-standing friend of Helmut and June Newton who knew and understood them well and who has provided precious insights. Baqué’s analytical, evidence-based study of Newton’s oeuvre is impressive and goes a long way towards revealing the deepest and darkest depths of his being. Her well-argued and entirely justified key premise is that Newton’s images are inextricably rooted in the emotions and traumas of his formative years. We are reminded of his childhood as the cherished son of a prosperous Berlin family, their ruthless persecution as Jews with the rise of the Nazi party after 1933, and his own escape, at the age of eighteen, after the terror of Kristallnacht (Crystal Night) in 1938.

Newton eventually settled in Paris and came to prominence in the field of fashion photography. He did so by radically subverting and conflating this and other genres, blurring the distinctions between his depictions of high style, his sharp social observations – particularly of the privileged and self-absorbed –, and his investigations of the tangled power-play of the erotic.

It has long been recognised that Newton’s images are deeply infused with his fascination with the traces of an old Europe and with the trappings and social codes of its haute bourgeoisie – the Europe and the way of life he had enjoyed as a child and adolescent. But as Baqué makes clear, this was not simply a romantic nostalgia. She has taken the courageous step of confronting the twisted ambivalence of Newton’s relationship with his German past and of his engagement with the imagery of Nazi fascism that resonates as a leitmotif through his oeuvre. The title of her book Magnifier le désastre (Magnifying the disaster) pinpoints Newton’s process of exorcising his demons by taking ownership of these darkly potent symbols, be they specific or implicit – symbols of threat, tension, violence, power, and domination –, and re-presenting them within his troubling, uncomfortable yet highly seductive iconography of style and eroticism.

Just five pages into her text, Baqué defines succinctly the mind-set of this obsessive image-maker, connecting cause and effect when she writes of, ‘the trauma, so painfully experienced yet never overtly acknowledged, of a young German Jew who suffered the horrors of the Nazis and determined thereafter that no-one would impose their law on him. For the pleasure of transgression. For the promise of a freedom that he would let no-one deny him.’(‘le traumatisme, douloureusement vécu dans sa chair mais jamais exhibé comme tel, d’un jeune Juif allemand qui subit toutes les infamies du nazisme et refusa dès lors que quiconque lui imposât sa loi. Pour le plaisir de la transgression. Pour la promesse d’une liberté qu’il ne laisse à personne le droit de lui soustraire.’)

This study opens pertinent and important perspectives on a challenging body of work by one of the most individualistic photographers of the second half of the last century. Baqué reminds us also of Newton’s considerable visual and literary culture, always lightly worn but a constant stimulus and resource; she sheds light on the vital contribution of Newton’s wife June, who shelved her own ambitions to support his; and she asks searching questions about Newton’s fears and fixations, tells of his frustrations as well as of his successes. Baqué’s book should be translated into English to provide a larger audience with a better understanding of Newton’s oeuvre and to stimulate further analysis and appreciation of this remarkable legacy.

There is a saying that revenge is a dish best served cold. Newton made a remarkable and rewarding life for himself, stubbornly setting his own guiding principles and pictorial agenda. He asserted single-mindedly the freedom of expression that represented his bitter-sweet revenge over the forces of darkness that had turned his life upside down in the 1930s. Refusing the facile badge of victimhood, Newton drew creatively from his shocking experiences, took energy from his traumas, dominated them to his own impressive creative ends.

Philippe Garner

Helmut Newton

Magnifier le désastre

Text Dominique Baqué

Published by Les Editions du Regard

Softcover

Size: 24.5 x 17.2 cm

280 pages

ISBN: 978 2 84105 387-2

Publication: September 2019

Price: 29 euros