Acclaimed as one of Mexico’s most important and admired photographers and photojournalists, Héctor Garcia described photojournalism as one of the most dangerous and attractive professions – trapped between the demands of information and aesthetics. Among images for which Héctor Garcia was best known are those that expressed his social consciousness including the 1968 student uprising, a 1960 image of painter David Alfaro Siqueiros behind the bars of the Palacio de Lecumberri prison, in Mexico, and the 1958 protest of mexican teachers, students and workers in solidarity with a railroad strike.

The president of the National Arts and Culture Council, Consuelo Saizar, was said to have called Garcia “The Photographer of the City” and a mythic figure who photographed the soul of Mexico in his work. Garcia saw himself as a witness, charged with chronicling the contrasts and struggles of the social classes in Mexico.

In a publisher’s description of the 2004 Turner Publishing book of photographs by Héctor Garcia, photographer Pablo Ortiz Monasterio said André Malraux called Garcia the creator of one of the cruelest images of our time, Niño en el Vientre de Concreto, – a disorienting black and white picture of a disheveled, dirty child folded up into an insignificant crawl space cut in a plane of concrete.

Monasterio says Garcia’s work as a photojournalist acquired great significance at the time because of his unwavering desire to express his ideology through images, unique among his colleagues. In a situation where corruption, hypocrisy, and lack of flexibility were day-to-day mechanisms of the government, Garcia’s ironic gaze opposed celebrations of power to events where social and labor conflicts raised by workers and students met with repression by the regime, particularly in 1958 and 1968. Death, religion, politics, and art were located as regions of identity by Garcia’s gaze, which was always careful of extracting allegories out of everyday facts, out of the reality that is evident to the eye, both in urban areas and in native communities.

In over 65 individual exhibitions of his work, Garcia came to be known for the emotional strength captured in the faces and postures of the ordinary and extraordinary people he shot. Today his images are in private and public collections in Paris, Washington, Houston, Mexico City and the Vatican as well as celebrated collections such as The Wittliff Collection. He was awarded the Mexican National Journalism Award three times. He also won the prize for the best ethnographic film at the Popoli Festival in Florence in 1972, having expanded his career to cinematography, and he shot still photos for several films made by Luis Bunuel. Shortly after Garcia’s death in 2012, Canal 22 produced a show as a tribute to the photographer, and the Museo de Arte Moderno held a retrospective of his work called Héctor Garcia: Visualidades Inesperadas.

Garcia’s career was championed by many important figures and his mentors included Celuloide magazine director Edmundo Valdés who recognized Garcia’s potential and sent him to the Academia Mexicana de Artes Y Ciencias Cinematográficas.

There he studied both still photography and movie making with Manuel Alvarez Bravo and Gabriel Figueroa. In 2012 Rafael Vargas quoted Garcia saying that Alvarez Bravo left him “more than just basics of the discipline but rather a concept of life, a path of limitless possibilities. I had wings but he taught me to fly.” Alvarez Bravo also sparked Garcia’s penchant for depicting the everyday life of lower class people in Mexico City. He took to avoiding the picturesque and was considered the first to really focus on class distinctions. Throughout Garcia’s career he made friends with and photographed both intellectuals and artists, among them Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, Delores Del Rio and entertainers such as Tin Tan, Maria Felix and Pedro Infante.

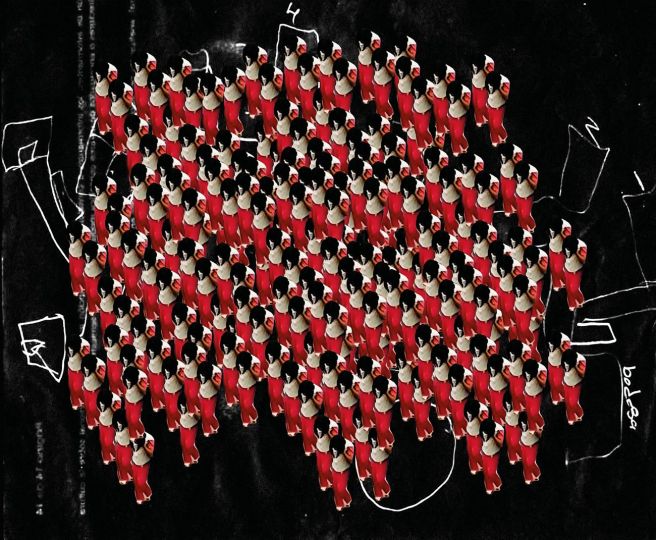

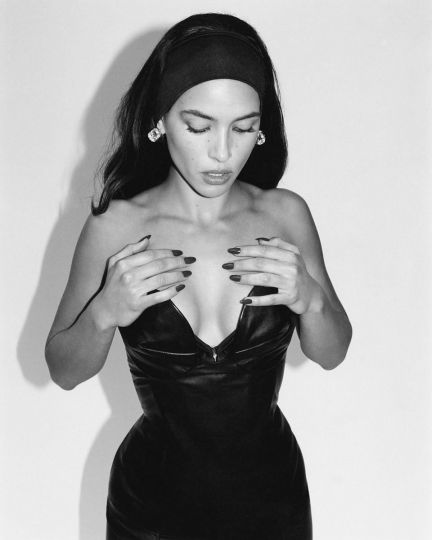

He took pictures of Kahlo in her bed and in her coffin, and Rivera was said to have called him an excellent artist. He used his camera with a sense of humor and irony as well, and had no fear portraying the social elite often in humorous and embarrassing situations that contrasted their lives with the poor. One image shows a woman in a strapless dress, which is stepped on by a man in a tuxedo at a social gathering, while another portrays a child using a large leaf as a rain cape.

By 1945 Garcia was able to get work with magazines and during his career his photographs appeared in many well-known publications including Cine Mundial, Excélsior, Siempre, Time and Paris Match as well as news agencies such as UPI, Reuters, the Associated Press and France Press. He also covered the presidential campaigns of Luis Echeverria and Jose Lopez Portillo.

Throckmorton Executive Director Kraige Block adds that, “Héctor Garcia was a genius at straddling the worlds of photojournalism and fine art. He said that all you need to be a good photographer was ‘eyes’ and an intention to see and to reflect on what is seen. He often took pictures with nothing more than a Nikon snapshot camera and enjoyed knowing that technology had made photo taking accessible even to young children. He quoted Pancho Villa who said to his troops when asked what to do, “You shoot, then check what happened.”

In 2008 Héctor Garcia and his wife formed the Maria and Héctor Garcia Foundation in Mexico City with five halls for permanent and temporary exhibitions. The foundation administers Garcia’s vast archives of more than a million photographs and hosts exhibitions by other artists. The Mexican government has a plan to preserve, categorize and digitalize the entire collection.

Hector Garcia, Sixty Years of Remarkable Photography

September 22 to November 26, 2016

Throckmorton Fine Art

145 East 57th Street, third floor,

New York, NY 10022

USA

www.throckmorton-nyc.com