The number of photographers to achieve a level fame beyond the ranks of their colleagues is small. Annie Leibovitz, recently commissioned to photograph the royal family to mark the Queen’s 90th birthday, might be one. Don McCullin will inevitably become even better known after he is played by Tom Hardy in a forthcoming film and Bill Cunningham was the subject of a superb tribute by Alice Florence Orr following his death in June. Harry Benson, Knightswood-born and once of the Hamilton Advertiser, has also received something more than just professional recognition.

A retrospective of his work, ‘Seeing America’, is currently putting Holyrood to good use. Benson, now 86, was back in Scotland to mark its opening and deal with the related media duties. He also attended a showing of ‘Shoot First’, a documentary about his life and work, shown at the Filmhouse in Edinburgh. Benson cites no influences save Lord Beaverbrook and only then because he gave him a job at the Daily Express in 1958.

While working for the paper he was tasked with travelling to Paris to photograph the Beatles for the first time. It was an assignment he initially protested, preferring to head to Uganda as originally planned, but he quickly came to realise the significance of the opportunity he had been given. His favourite photograph is the image of the Beatles having a late-night pillow fight in their Paris hotel after Brian Epstein told them they were number one in America.

Benson travelled with the band to America for that first momentous tour in early 1964. At the start of ‘Shoot First’ the footage of the band’s arrival at JFK airport is shown. It’s footage any fan of the Beatles has seen countless times but it was the first time I’d properly paid attention to the photographer at their back as they descended from the plane. The adulation of the crowd was sucking them down to the tarmac and the future, but they turned on the command of Benson. One photograph in the exhibition shows them looking towards the camera with a collection of American cameramen on the ground below. This image, capturing the Beatles view as they arrived in America and thus a significant cultural moment, also felt new. How had that happened?

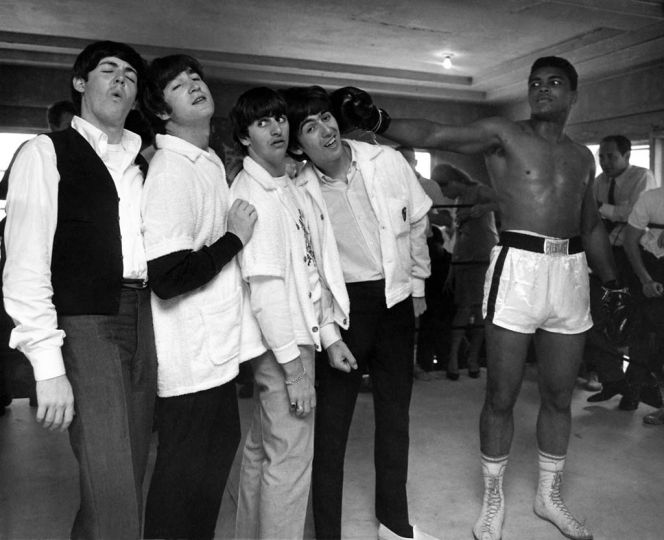

Perhaps the most famous photograph Benson took on that tour was of the Beatles meeting Muhammad Ali – Cassius Clay as he was then – at the Fifth Street Gym in Miami. Ali, standing at least a head taller than any of Liverpudlians, is shown with his right arm extended as if delivering a jab. George Harrison is directly on the receiving end but the other members are posed with heads inclined like collapsed dominoes or as if demonstrating the principle of Newton’s Cradle. The band was in Florida to film the second of its three appearances on the Ed Sullivan Show and Ali was training as the contender ahead of his championship fight with Sonny Liston. The Beatles wanted to meet Liston but the feeling wasn’t mutual. He had attended the Ed Sullivan recording in the company of the fight promoter, Harold Conrad, and was reported to have said: ‘My dog plays better drums than that kid with the big nose’.

David Remnick credited Conrad with arranging the fall-back meeting with Ali but other accounts, including Benson’s, suggest that the Scottish photographer was the instigator. Robert Lipsyte, who opened his Time magazine cover story on the death of Ali by recounting his meeting with the Beatles, claimed ‘the photographer’ had come up with the idea after the rebuff by Liston who, in any case, had the personality of a graveyard in the gloaming. When the Beatles arrived at the Fifth Street Gym they were annoyed at having to wait for Ali. They made to leave and were only prevented from doing so by a couple of state troopers. Apparently recognising none of their iconoclasm reflected in Ali, they told a young Lipsyte that Liston would win easily but this surliness was flattened by the arrival of Ali’s charisma. They took to discussing financial matters and posing for pictures. Ringo Starr, who had earlier stomped about the place demanding to know where Ali was, ended up in his arms being cradled like a baby.

Most accounts have it that Clay tamed the Beatles. It’s an episode that’s incongruous with the popular memory of that visit but John Lennon testified to its veracity when he told Benson they had been made to look like fools. The band didn’t speak to him for a time afterwards. But images of the encounter, shorn of niggles, are justly famous for capturing perhaps the five personalities who would become emblematic of the decade’s sharpest cultural changes. As Remnick put it, they were ‘parallel players in the great social and generational shift in American society’. Crucially, Benson managed to capture them in close proximity to key events that would help them to instigate this shift. The Beatles had just hit America like a cymbal and within a week of the encounter Ali would defeat Liston to become heavyweight champion of the world for the first time.

The Beatles turned Benson around and sent him off in a different direction but the distance travelled from that point was a matter to be negotiated by his talents. He worked out of New York for a time, covering British interest stories for the Express before being taken under contract by Life. He was able to capture America’s dark spasms during the 1960s, notably the civil rights movement, racial unrest, domestic protests against the Vietnam war, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy.

Photographs in the exhibition at the Scottish Parliament include a hooded and robbed mother with her baby at a rally of the United Klans of America in Beaufort, South Carolina; an African-American with legs spread being searched against a church noticeboard during the Watts riots; and a lonely African-American father in an airport holding a folded flag slightly away from his body, as though it might be contaminated, after attending his son’s burial at Arlington.

Perhaps the most harrowing photograph on display was taken as Bobby Kennedy lay, fatally shot, on the floor of the Ambassador Hotel. The true and abrupt horror of the moment is captured in a photograph of his wife Ethel, caught as though looking directly at Benson. Her face is partially obscured by her outstretched hand and it’s hard to tell if she was trying to create a pocket of air for her wounded husband or if she was trying to prevent Benson from documenting the awful moment. Regardless, it’s the look of desperation on her face that leaves the longest impression. In another photograph from the scene a campaign boater hat lies on the floor, a puddle of blood lapping at the brim.

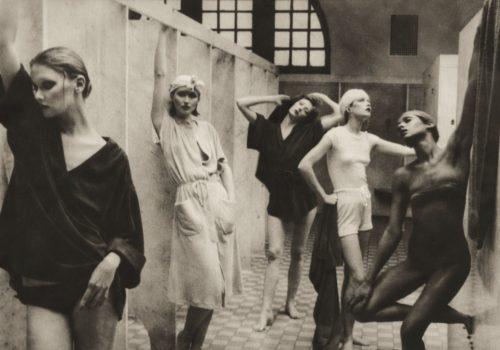

Working for Life and other magazines, Benson photographed celebrities and public figures for years, always encouraging the spontaneous approach that might give a glimpse into something of the private. Among the best displayed part of the exhibition are Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in the Vermont snow, face upturned and beseeching; Jack Nicholson, photographed in 1975, with a number of facial expressions you would be pleased to carve on a pumpkin; Bobby Fischer in Reykjavik, scene of his famous victory over Boris Spassky, with his eyes closed and faced bowed against a horse as though willing an exchange between whatever it was that so troubled him and the animal’s serenity; and Frank Sinatra wearing a cat mask, complete with whiskers, as he accompanied Mia Farrow to Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball.

An important element of Benson’s renown is the fact he has photographed every American president of the post-war era with the exception of Harry Truman. He photographed Ronald and Nancy Reagan in the spring of 1985. She was wearing a long black dress, his attire was finished with a black bow tie and they are pictured in a dancing pose.

The picture appeared on the front cover of Vanity Fair in June 1985 and the accompanying article was written by William F Buckley Jr, a close friend of the Reagans and a figure often credited with altering the political atmosphere in a way conducive to their capture of the White House. He likened them to ‘Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, romancing and kicking up their heels’. This was not, he continued, ‘an easy thing to do, never mind the authentic high temperature of mutual devotion: there is in the west a tradition against chiefs of state engaging in visible, let alone ostentatious shows of biological informality’. If the photograph has an outlaw quality, perhaps that explained the impressive sales of the issue, which has been credited with helping to save Vanity Fair after several difficult years.

Susan Sontag was, among other things, the partner of Annie Leibovitz, and she once wrote that ‘memory freeze-frames; its basic unit is the single image’. If it’s true that something of the power of photography lies in its close accordance with the functioning of memory, then it’s also only a partial explanation: An awareness of context, artistry and composition are also important factors in determining any image’s longevity. The best of Benson’s pictures combine all these qualities. They are like the folded page corners of a long book you’ve read before, inviting you to recall key moments and go a little deeper into their specifics.

Alasdair McKillop

Alasdair McKillop is an author of the Scottish Review.

Harry Benson: Seeing America

Through December 3, 2016

Scottish Parliament

Edinburgh EH99 1SP

Scotland

http://www.parliament.scot/