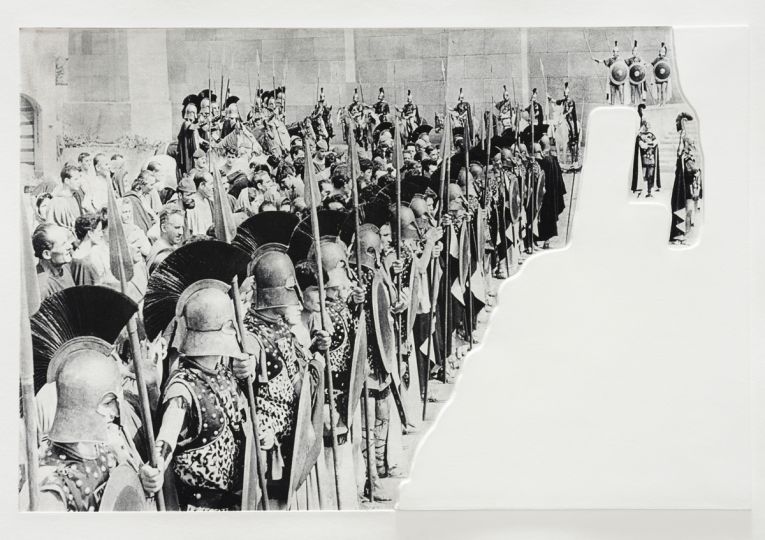

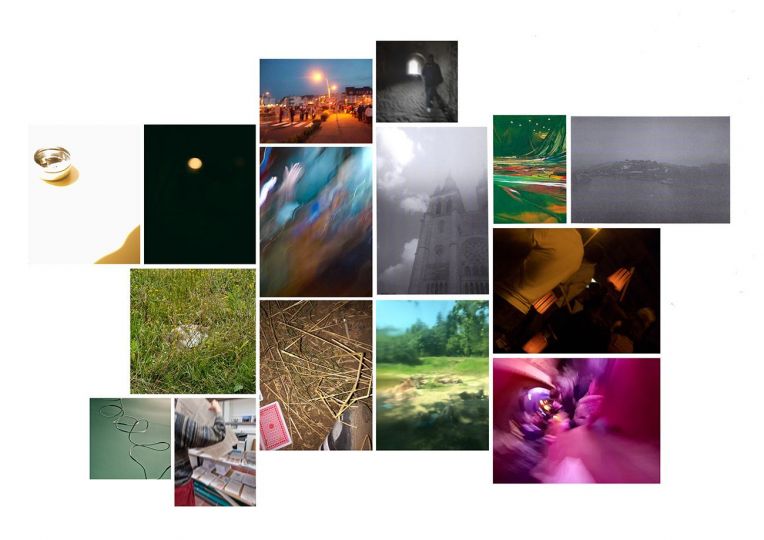

Drawing upon art historical sources and Eastern and Western decorative traditions, Fred Tomaselli’s works explode in mesmerizing patterns that appear to grow organically across his compositions. Starting in 2005, Tomaselli has developed a body of works on paper that transform the front page of The New York Times with gouache and collage. The surreal compositions are ruminations on the absurdity of news cycles and provide him with a space to respond to a variety of issues – from regional anecdotes to global crises. Fred Tomaselli spoke to Andrea Blanch, from Musée Magazine.

Andrea Blanch: You were quoted as saying in the LA Times, “I get to talk back to The Times, I get to be an editor.” Was this your intention from the start of the The Times?

Fred Tomaselli: Originally, I don’t think there were any intentions. I started out with ideas that were revealed through the process of play. Those ideas consequently informed the subsequent work; eventually a set of intentions evolved out of the process. One of the processes was becoming part of this hive that puts together the paper through this collectivity. I feel like I’m just another editor with this group of fact checkers, writers, editors, and photographers. And that just appealed to me,I have always had the sense of the collective that I’ve always been involved in with my collages. Prior to this project, I used all these images that were, in some part, created by others but always nameless. Now I have all these with bylines that give people credit.

It gives you a parameter to work with, no? When you’re doing your own work, you’re working with a blank canvas. This gives you something to feed off of. Could that be helpful?

Well it keeps me off balance. The images are not necessarily what I might be gravitating to if left to my own devices. So, I kind of have to meet them on their own terms and be a little off balance to try and deal with that. I think that’s a good thing for me at this point.

You’ve been doing this for twelve years, what would make you stop? How will you know when it’s completed?

Maybe when they stop printing newspapers.

Is it about suggesting the viewer to reflect on what they see every day through a different perspective?

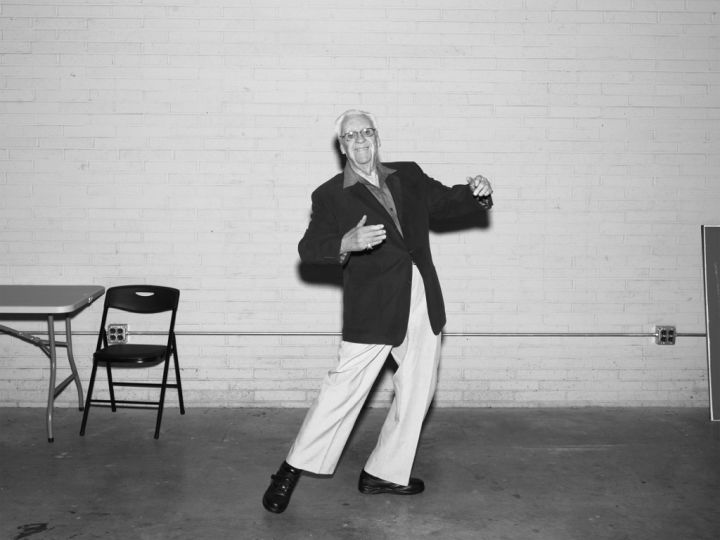

That’s part of it. Even though I’m dealing with an artifact, it deals with this social world, this world of the social and the political. When it comes to actually making the work, in a lot of respects, my motivation is simply just to amuse myself. I don’t even think about the viewer; I just make the things I want to see. Later on, I think about where the viewer fits into all of that. If I don’t think the viewer has a place or can find a way in, or that it seems too obtuse, then I just shred them. I shred a lot.

I’m not saying this is consciously your intention, but it’s like Marshall McLuhan said, “The medium is the message”. This has become an asset to your political arena, whether this was your intention or not. Have you thought about this?

I’m a pretty political person. You know I’m obsessed with the news and I consume it through radio, through TV, and through print media. And I do believe that the Times is inherently political and the news is often horrible, but the world is also funny, beautiful, absurd, and mysterious. I try to get all that in too. In some respects, I’m imposing this other kind of reality on this grim reality of the Times. I don’t mean for it to be escapist, but rather to interject some other kind of space by using the Times as a launch pad for this other reality. That being said, my political persuasions do sneak in all the time and I own it.

You’ve done escapism art but you’re very focused on the press, don’t you find that unusual?

I think most of our reality seems pretty slippery and that includes the media, maybe even more so. One could make the argument that the media dictates our very desires, our very core of who we are as people, constructs that we spend from certain seductive mechanisms that the media has sort of harnessed. I think that’s one of the reasons, or one of the attractions of playing with the media, playing with the Times, to play with this manipulator of our beings. I would say that, getting back to this idea of escapism; the presumption of impartiality really is a fiction that deserves some general deconstruction. Newspapers choose what to spotlight and what to ignore and I don’t necessarily believe that it’s less escapist than anything else when you get down to it. The New York Times is, as good a paper as it is, still guilty of some of these things I’m referring to. But since it is the paper record, it is supposedly the arbiter of objectivity. It seems like a perfect foil to play around with that very idea.

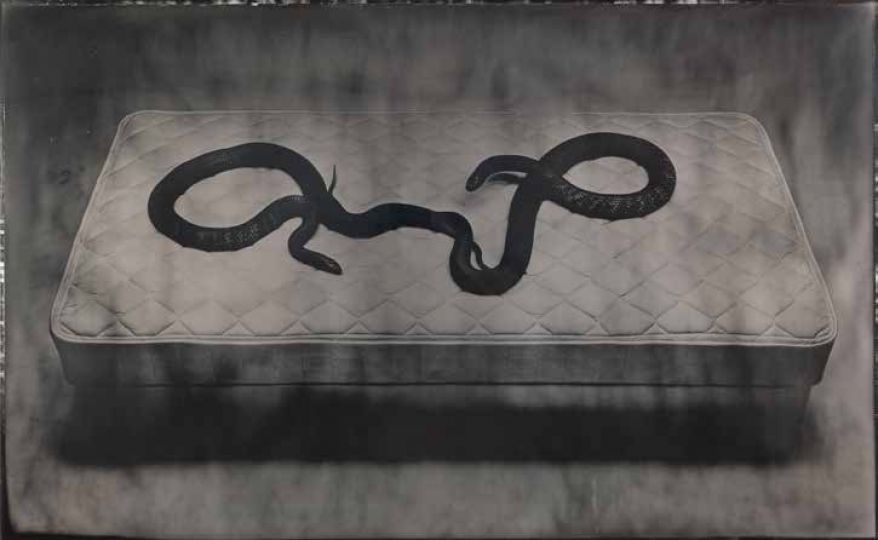

A big part of your artwork is based on your experience with drugs.

It started out that way. Actually, it started out with theme parks in the 80’s. I did a lot of installations that were sort of like punk rock, light and space that were very informed by escapist amusement and theme park type installations. And then from there, from these assemblages and installations, my thinking, because I was already interested in the landscape of the unreal, it was not too big of a leap to go looking into drugs. And to see how the rhetoric around psychedelic drugs was really similar to the rhetoric around paintings. This idea of this window to another reality, this art object as a transportational vehicle to take you to other dimensions, it seemed a lot like what people say when they’re talking about drugs. So I played around with those corollaries and I evolved back into being a painter; I had left painting behind for about 10 years to do this installation work, and now it’s sort of migrated to that same obsession with reality and perception that has been culturally modified and has now been moved into the New York Times and into the media. But yeah, I don’t remember what your original question was.

You said you stopped painting because you’re doing the New York Times. I’m wondering where you picked this up?

In the New York Times works and in these big ones, I occasionally introduce leaves, real leaves, into the work because I’m working on a scale where it’s possible to put leaves into the work. There’s always been this tension between what’s real, what’s photographed, and what’s painted in my work. Sometimes, it’s a little hard to tell the difference. Occasionally I’m achieving that, but you’re right because these are just works on paper. There is little of the introduction of objects into the work right now. It’s primarily just collage, photo collage, and paint and that’s a challenge to me.

And why collage? I’m wondering what turns you onto it and what kind of mindset you need for it?

I come out of this sort of cut and paste culture; we sample other cultures and integrate them into our lives. So, collage to me has always seemed really natural. It may have descended out of people like Picasso or Braque back at the turn of the century, but it’s been the constant that keeps coming up throughout history. But I really do think I’m sort of comfortable in this idea of having a pre-existing image, or having thousands of pre-existing images, and then sort of playing with them. Maybe that comes from me playing with component toys from when I was a kid like Legos or Lincoln Logs, this idea of assembling a thing with one premade piece at a time. It feels really natural to me and I have to listen and be attentive to my sensibility.

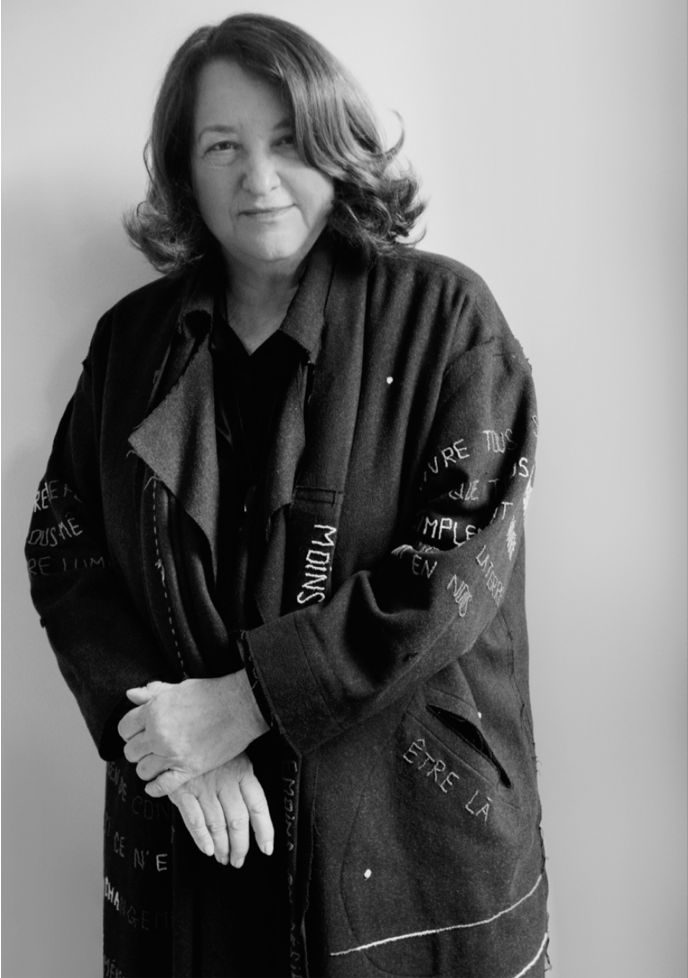

Interview by Andrea Blanch

Andrea Blanch is the founder and editor in chief of Musee Magazine, a photography publication based in New York, and a fashion, fine art and conceptual photographer.

This interview was published in the issue 16 of Musée Magazine that came out in October 2016 and is available for $65.