From April 5th to June 1st, 2025, the 15th edition of the Festival Circulation(s) – Festival of Young Photography in France, will take over the 2,000m² space of the CENTQUATRE-PARIS. Among the 23 emerging photographers from 13 countries, Wang Tianyu will present her series Hiding and Seeking (2022-), a poignant work that examines domestic violence and power dynamics through an intimate and political lens.

Originally from Zibo, in Shandong province, China, Wang Tianyu honed her vision at the Zhejiang University of Communication (CUZ) and then at the École cantonale d’art de Lausanne (ECAL). Sharing her time between Lausanne and Paris, she has developed a photographic practice rooted in this “discomfort” felt at the heart of everyday behavior. Her work navigates between memory, lived and imaginary bodily experiences. Through photography, she explores the fine line between the banality of everyday gestures and the realities hidden by systemic oppression, particularly patriarchal oppression.

“Fighting the Everyday with the Everyday,” a Visual Subversion

Wang Tianyu’s approach is characterized by a subversion of the usual visual codes of everyday life. Through her images, sometimes surreal, sometimes absurd, she deconstructs the inherent attributes of ordinary objects and situations, both visually and narratively. Through this method, she offers a way of “fighting the everyday with the everyday,” seeking to reveal the invisible through the reappropriation of the banal.

Hiding and Seeking, this childish game symbolizing innocence, exudes a disturbing strangeness. The artist displays eight works that reveal the hidden violence and invisible oppression inflicted on women in the family sphere, hidden beneath the veil of everyday banality. In this space obscured by the shackles of tradition, violence reigns supreme, invisible, permeating every part of our existence. We are all in this game, both dangerous and paradoxically reassuring, a game where there is never a true winner.

These images, oscillating between reality and imagination, exude a suffocating oppression. Washing hands, getting dressed, smiling—so many ordinary fragments that, beneath their apparent banality, betray disturbing truths: violence lurking in the shadows, oppressive silence, and the injunction to submit. The artist thus transforms the viewer into an involuntary witness to a structural violence that is usually invisible.

The “New Photographic Action,” Redefining the Relationships of Gaze

Wang Tianyu’s singularity lies in her innovative method, which she calls “New Photographic Action.” Inspired by the concept of “Photographic Actions,” [1] she develops a working method where performance becomes the creative process, simultaneously assuming the roles of photographer, photographed subject, and image editor. This triple role subverts traditional power relations and the unidirectional vision of the gaze in photography, proposing a new economy of gaze. Through this superposition of roles —subject, object, and observer— it reestablishes a relationship of parity between the observer and the observed.

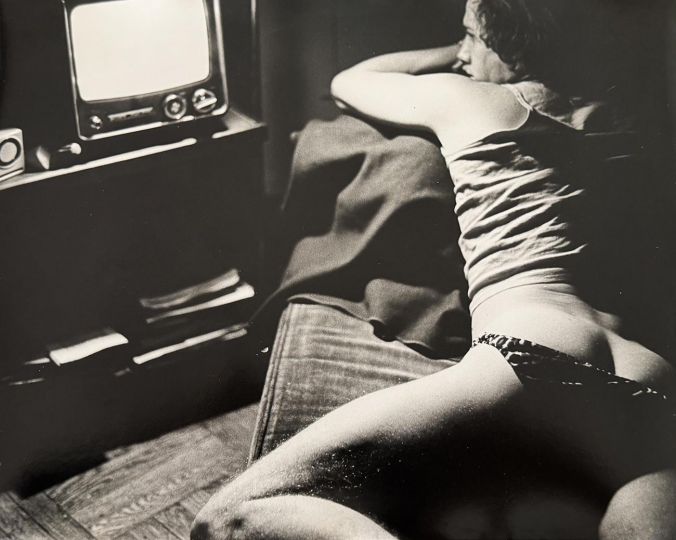

As Laura Mulvey theorized in Plaisir visuel et cinéma narratif (1975), conventional visual culture often shapes women as passive objects of the “male gaze” rather than active, autonomous subjects. Wang Tianyu seeks to reverse this dynamic. For example, in Put on or take off? (2024), she depicts the mundane action of women dressing or undressing beyond a sexualizing gaze. Through the use of a fast shutter, she captures fleeting postures where the usual order and direction of gestures are disrupted, fabrics pulled and caught between bodies. These images disrupt our conventional perceptions of the female body, making tangible its destiny by constraining while revealing, in the tension between clothing and body, a force seeking liberation.

The influence of Chinese painting, a complex temporality

Introduced to painting from childhood, Wang Tianyu draws inspiration from Chinese pictorial tradition, particularly the “Three Types of Distance (sān yuǎn)” technique, specific to Chinese landscape painting. This technique allows her to combine different viewpoints within a single image, creating a layered and complex visual narrative.

The moment of reaction, the cake was smashed (2024) perfectly illustrates this approach: the smiling face covered in pastry cream hides the hand that throws the cake, while in the background, another face tries to dodge the aggression. This layering of shots allows the viewer to simultaneously grasp several temporalities and points of view, in order to bear witness to the authentic reaction to this implicit violence within a normally festive situation.

The exhibition’s scenography extends this reflection. Like Chinese painting, where time is often expressed in layers rather than linearly, the artist arranges several images in a sequence. Using the picture rail as a canvas, she interweaves conventional rectangular formats with freer compositions to create what she calls a “temporal sequential process.” This presentation engages the viewer in an oscillation between static contemplation and dynamic observation. It thus transforms the act of looking into an active experience, requiring the viewer to make eye movements in response to the freeze frames, leading to moments of hesitation in the face of the complexity of the photographs and the difficulty in interpreting the emotions they represent.

The Context of Chinese Feminism: A Decentralized Resistance

Wang Tianyu’s work also takes place within a significant political context. The year 2025 will mark the thirtieth anniversary of the World Conference on Women in Beijing (1995). Since the imprisonment of the “Feminist Five” [2] in 2015 for planning activities against sexual harassment, the public space of the Chinese feminist movement has steadily shrunk, forcing organizations underground and then gradually migrating online. Social media has become an alternative public sphere, catalyzing debates on gender issues. While the #MeToo movement in 2018 brought feminism back into the Chinese public arena, censorship and repression have primarily reduced it to forms of individual resistance. In this increasingly restrictive context, it is the interconnectedness of these isolated actions that now forms a decentralized force of resistance.

Faced with the narrative shift in official discourse, from “women holding up half the sky”[3] to a rhetoric centered on the traditional family, and in the wake of the law on the reflection period before divorce [4] and the three-child [5] policy, what is the future for Chinese feminism? Wang Tianyu’s individual approach in Hiding and Seeking perhaps outlines an answer. Her work, rooted in her personal experience, is also imbued with political resistance.

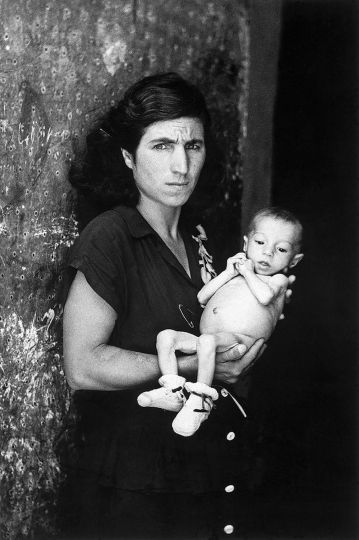

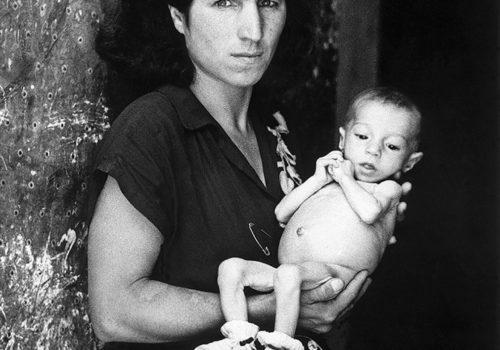

In Spider (2024), she photographs herself as countless women victims of domestic violence, instinctively curled up under their clothes, reaching out to crawl or cry for help. The photographs intertwine to form a vast black creature, like a cocoon. If Louise Bourgeois subverted traditional gender roles through her sculpture Maman (1999), thus representing a horrific femininity, Wang Tianyu’s spider, composed of folded female bodies, powerfully evokes a collective female trauma.

Rebellion in Images, an Aesthetics of Resistance

“Saying yes in the night shot through with glimmers, and not simply describing the no of the light that blinds us,” writes Georges Didi-Huberman. Wang Tianyu’s images, like “firefly images,”[6] illuminate invisible oppression, resisting the blinding glare of dominant discourses. The artist thus achieves a true rebellion in images through her photographic practice.

By deliberately concealing faces, she also blurs the line between individual and collective. Her work not only symbolizes personal suffering, but also reflects the shared traumas of the collective female experience. For the artist, connecting these individual actions not only serves as a weapon against patriarchal oppression, but also paves the way for broader political transformation.

Although she comes from a Chinese province with deeply rooted traditions, Wang Tianyu’s “cultural reflexivity” [7] allows her to cast a critical eye on her native cultural context. She acutely perceives and reveals the invisible structures and power relations that permeate it, offering, through photography, new possibilities for individual resistance.

Through this universal game of hide-and-seek, the artist invites us to ask ourselves: what, ultimately, lies beneath these images?

Deng Qiwen

Festival Circulation(s)

From April 5 to June 1, 2025

CENTQUATRE-PARIS

5 rue Curial, 75019 Paris

Exhibition open Wednesday to Sunday, 2 p.m. to 7 p.m.

https://www.festival-circulations.com/

[1] Photographic actions: This term comes from the Performing for the Camera exhibition at the Tate Modern. It refers to actions carried out by artists whose final result is an image, such as filming the process of creating a painting.

[2] Feminist Five: A group of five Chinese feminists arrested in Beijing on March 6, 2015, for planning a protest against sexual harassment on public transport.

[3] “Women who hold up half the sky”: According to Geng Huamin and Zhang Leilei’s article, “Les femmes peuvent soutenir la moitié du ciel : une enquête historique,” Beijing Guancha/Beijing Observation, No. 3, 2015, this expression, taken from a folk proverb, was first recorded in Le Quotidien du Peuple in 1956. It was later taken up by women’s groups during the Great Leap Forward (1957-1961), before being disseminated nationally by the All-China Women’s Federation and senior leaders, becoming part of the state discourse on women’s emancipation.

[4] The Divorce Cooling-Off Period Law: A new regulation implemented by the Chinese government on January 1, 2021, requiring couples wishing to divorce to wait thirty days before confirming their decision.

[5] The Three-Child Policy: A family planning policy in the People’s Republic of China, allowing a couple to have up to three children, introduced on July 20, 2021.

[6] Didi-Huberman, G., Survivance des lucioles, Éditions de Minuit, 2009, p. 133.

[7] Cultural reflexivity: Refers to the process of critically reflecting on one’s own cultural assumptions, values, and perspectives, as well as how these elements influence interactions with other cultures.