Presidential Photography: A Conversation with Vicki Goldberg by David Schonauer

This month, the presidential primary elections begin in the United States, and Americans begin the long process of deciding who will occupy the White House for the next four years. Millions and millions of dollars will be spent in the effort to claim the executive mansion, which is of course not just a mansion, but also an emblem of power. Ironically, the White House itself is not especially imposing, as far as state residences go—it was designed to be anything but regal. Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the French architect who designed Washington, D.C., wanted to build a European-style palace for the president to live in, but George Washington wanted something far less monarchical. Washington (who left office in 1797, before the building of the White House was completed) didn’t like the word palace. He preferred to call the new residence “the President’s House.” But in fact it wasn’t really even the president’s house. It was the people’s house—they held the title on it and decided who would and would not live there.

“Someone once said it was the only house that every American owns, and that is quite true,” says Vicki Goldberg, the critic, biographer, and photo historian whose new book The White House: The President’s Home in Photographs and History (Little, Brown $35) was recently released, just in time for the coming election season. The book is a thoughtful reminder of the transient nature of White House tenancy. “The president in office might change every four years, but the house persisted, a constant sign of what the country stood for,” she writes in the book’s introduction.

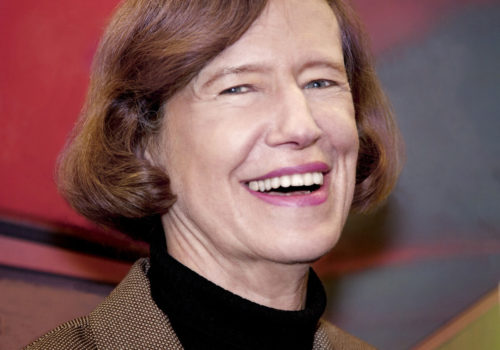

Goldberg is one of America’s leading writers and lecturers on photography. Among her books: Margaret Bourke-White: A Biography (Harper & Row, 1986) and Photography in Print: Writings from 1816 to the Present, named by the Wall Street Journal in 2006 as one of the best books ever written about photography. She has also contributed to the New York Times and Vanity Fair, among other publications. Her new book features photography from the archive of the White House Historical Association, a non-profit and non-governmental organization. Many of the images have never been published before, most will be unfamiliar to readers, and all are presented with new historical and cultural insights from Goldberg. “I was very interested to think that I could make a chapter about the presidential relationship with the media, and one on involvement with technology, because I think that photographically neither of those had been done,” she says.

Goldberg chose some 900 images from the association’s 5,000-image archive, then narrowed the selection down to the 278 that appear in the book, dividing them into chapters like “Presidential Portraits,” “The East Wing,” and “Cameras at the White House.” As Clinton White House press secretary Mike McCurry writes in the book’s foreward, Goldberg has constructed a “hybrid of history and photographic criticism” that traces changing communications and a changing society. The most intriguing images come from chapters on presidents’ families and even presidential pets, which offer rare and touching behind-the-scenes glimpses of life inside the White House. The treasures include an exquisitely lit portrait of President Woodrow Wilson holding his first granddaughter in 1915, credited to the Clinedinst Photo Studio of Washington, D.C. There is also a 1902 shot of Theodore Roosevelt Jr. with his pet macaw Eli Yale, taken by Frances Benjamin Johnston, one of America’s earliest female photographers, and a hilarious 1968 photo of Lyndon Johnson howling along with his dog Yuki, shot by the first civilian official White House photographer, Yoichi Okamoto. In images such as these we see the people who have lived in the people’s house with fresh eyes.

Before the holidays—while the Republican Party battle for the Iowa caucuses was taking final shape—I chatted with Goldberg for the better part of a morning about photography and the presidency. This was not the first time I’d spent an hour or two with Vicki talking about pictures: In bygone days, I edited a book-review column she wrote for American Photographer magazine—she was a patient and charming tutor on the finer points of art criticism—and she was kind enough to contribute a number of longer essays to American Photo magazine when I was the editor there. Vicki speaks like she writes: with precision, authority, and humor, all of which are excellent qualities to bring to bear on topics like power and politics. She is also unceasingly inquisitive, and that too is valuable, because pictures, like presidents, are not always what they seem, as you will see.

David Schonauer: Vicki, how did this project come together?

Vicki Goldberg: It started with a phone call from Neil Horstman, the president of the White House Historical Association. He told me they had this great digital archive of photographs and wanted to know if I thought they had enough material for a book. They sent me 300 images, about half of which I’d never seen. So I went down to D.C. and looked at their entire collection on a computer, and I thought, “Oh boy, yeah, there’s a book here.” I picked out 800 or 900 images, and then I tried to figure out how a book could be made out of them.

David Schonauer: I was interested in the conceptual structure you came up.

Vicki Goldberg: I knew I didn’t want to do it chronologically. So I looked at things that seemed to fit together and made all these various chapters.

David Schonauer: I was surprised to find that you put in a chapter about presidential pets. But I came to realize that pets have really been a big part of the White House story.

Vicki Goldberg: You know, the last 16 presidents have had dogs. They haven’t all had cats, but they’ve all had dogs. The dogs actually started with George Washington, who had hunting dogs. I was interested in all the pictures I found of White House pets, at first because they were just a lot of fun to look at, but also because I am interested in the media and how it works. In the 19th century, the media got into covering White House human-interest stories—first it was the wives, then the children, then it was the presidents relaxing, and then it was the pets.

David Schonauer: So the coverage of pets was part of a cultural shift?

Vicki Goldberg: Pets became more important culturally in the 19th century. Raising pets was thought to be an educational experience for children. So that was a piece of it. But it’s even a bigger story when you’ve got people with rather extraordinary pets, like Teddy Roosevelt. His children had all these hamsters and snakes and parrots. Well, it became catnip for the newspapers. Excuse my unintentional wordplay there.

David Schonauer: Another surprising aspect of the book is how early on in the country’s history the White House became a symbol of the United States itself. It was never just a residence. And much of this symbolism was communicated through illustrations.

Vicki Goldberg: The first representation of the White House was published in 1807. It was an engraving that was done for the cover of a book written, ironically, by a British man. He had done a book about this new country that the British were naturally interested in, and he needed a visual for the cover that would emblemize the United States. He had to pick something that people would recognize as being American, and he chose an illustration of the White House. So it was already a symbol of America, even then.

David Schonauer: Why do you think it came to be so recognizable?

Vicki Goldberg: Partly because it was so different from the residences of the heads of state of countries in Europe. Even later, when there were republics in Europe, the heads of state usually lived in old castles. The White House was clearly not a castle. When that particular book was published in 1807, the White House had neither a north nor a south portico. It was an unpretentious, un-kingly building, and that did symbolize the non-monarchical government the country had established.

David Schonauer: So it became a symbol of power and the center of government—more so than the U.S. Capitol Building.

Vicki Goldberg: Yes, and very early on the White House became known as “the people’s house,” which was another very interesting example of republicanism. In 1801, Thomas Jefferson opened the house to everyone, every day. Entrance eventually had to be restricted, because visitors became intrusive into the running of the government.

David Schonauer: You have an interesting story about Harry Truman and his ideas about redesigning the White House in 1946…

Vicki Goldberg: Harry Truman wanted to add an office building to the White House—an idea that almost everybody else hated. A Washington newspaper reminded him that he didn’t own the house—that he only had a lease on it, and that the lease could be terminated rather quickly.

David Schonauer: Who was the first president to appear in a photograph?

Vicki Goldberg: The first president to appear in a photograph was actually an ex-president, John Quincy Adams. He served as president from 1825 to 1829, before the invention of photography, but later, in 1843, he was photographed for the first time. He had already had many portraits of himself painted and drawn, of course. It was very important in a democracy, where people voted, to have an image of the person you were voting for.

David Schonauer: Did photography fundamentally change the way people viewed the president?

Vicki Goldberg: The 19th century was a time when people believed that a person’s character was visible in their face. It was also a time when people believed very strongly in realism, and there was always a bit of distrust about artistic renderings of famous people—quite correctly, I believe. Photographs of leaders were seen as a more trustworthy representation. By the way, John Quincy Adams ended up sitting for seven photographs, all of which, he said, were too true to the original.

David Schonauer: You mention in the book that that first photograph of Adams—it was a daguerreotype—was for many years incorrectly thought to have been made by Southworth & Hawes, the famous photographic firm in Boston.

Vicki Goldberg: It is a Southworth & Hawes picture, but it’s a copy of a daguerreotype done by somebody earlier.

David Schonauer: You also point out that imagery of the president was used for campaign purposes from the early days of the republic. But when did the president become what we now think of as a celebrity?

Vicki Goldberg: That really happened first with Lincoln. That was about the time that the word celebrity actually began being applied to people. Before that, you had the celebrity of certain occasions, but people were not celebrities. And I think that change occurred in large part due to changes in photographic technology.

David Schonauer: Explain that…

Vicki Goldberg: Among other changes that occurred at the time, the French devised the carte de visite in 1854—the little photographic visiting cards that became immensely popular. They were small and cheap. People collected them and put them in albums, and that helped lead to the celebrity craze. People could create albums with images of well-known people—pictures of Queen Victoria, for instance, or pictures of Abraham Lincoln.

David Schonauer: And Lincoln really benefited politically from photography…

Vicki Goldberg: Yes, very much. When Abraham Lincoln arrived in New York in 1860 seeking the Republican Party nomination for president—this was when he gave his famous Cooper Union Address, which helped establish him as a viable candidate—he was a man nobody in the East knew anything about, except that he was a backwoods lawyer from Illinois, and that he was ugly. He was certainly gangly—he was six-feet-four inches, which was extremely uncommon at that time, and he wore a very plain black suit, and if he wasn’t really ugly, he was certainly plain. When he arrived in New York City, the Republican bigwigs met him at the train and took him straight to Mathew Brady’s photography studio, and Brady took his picture. Brady posed him very carefully, with Lincoln’s hands on a book. That was not an uncommon pose at the time—it meant that the subject was literate. Brady probably straightened out Lincoln’s suit and dusted off any train dirt, and he raised Lincoln’s collar a little bit. Lincoln said something like, “Oh, I see you’re trying to make my neck look a little shorter, Mr. Brady.” And Brady said, “Yes, that is so.” And then when Brady developed the picture he lightened Lincoln’s swarthy complexion—you could do a lot, even before Photoshop. He made Lincoln look not like an ugly backwoods lawyer, but instead like a dignified, serious, intelligent man—in short, like presidential timber. Thousands and thousands of copies of that photograph were published and disseminated. Currier & Ives, the very successful printmaking company, sold copies of it at 25 cents a photo. You could stick the picture in a hat band, you could stick it in a pocket, you could stick it in your wallet, and you could send it through the mail. And it made it possible for many, many people to see what this candidate looked like. Besides that, the tintype had recently been developed, and photographs of Lincoln were made into campaign buttons—the first campaign buttons ever produced. So Lincoln became in a certain sense a celebrity. That helped get him elected, and after that he knew the power of photographs. Later on, Brady went to the White House and was introduced to the new president, and according to Brady, Lincoln said, “Oh, I know Mr. Brady—his photograph helped get me elected.”

David Schonauer: Lincoln in fact was photographed quite often…

Vicki Goldberg: Lincoln was photographed over 100 times. He sat for photographers all the time—he knew just how important they were in keeping his image before the public.

David Schonauer: As you mentioned earlier, the media began looking for ways to tell human-interest stories about the president, and that is certainly reflected in some of the images in the book. I was fascinated, for instance, by a Mathew Brady picture of James Garfield, the 20th president, reading to his young daughter, and the way you broke it down. The image shows Garfield’s face, but the child is turned away from the camera.

Vicki Goldberg: I was really curious about that picture when I first saw it, because the child is almost obliterated in it. I asked a couple of experts about it, and they said that kind of pose was not entirely uncommon in the 19th century. But I have since seen the extended take from that portrait session, and there is another image in which you see her face. Also, it’s significant that he is reading to her. The issue of childhood reading was very important in the 19th century. In fact, the U.S. had a very educated populace at the time. If you read some of the wonderful letters written by soldiers during the Civil War—these were farmers, and they could really write well.

David Schonauer: And in the photo, which is carefully posed, Garfield comes across as a prototype of a nurturing father.

Vicki Goldberg: The picture was probably made before Garfield became president, but yes, it does portray him rather virtuously. At the time this photo was made, the status of children had changed in this country. They were no longer so important economically—more and more people lived in cities, and children weren’t needed to work on farms as much as they had been. The family became a central social unit, and generally it was the mother’s job to educate the children and to make sure they were good citizens. Fathers were also important, and I think a photograph of a president with his child would make an interesting picture for Americans to see. It would have said, yes, fathers should be involved in their children’s education as well, and reading to your children is meaningful. There is also a picture of Lincoln that looks like he’s reading to his son Tad—Tad was the only member of his family that Lincoln was photographed with—but in fact Lincoln is not actually reading. The book in the photo is a book of pictures that the photographer had given them as a visual device to link the two figures closer together in the frame.

David Schonauer: You write that portraits of great men were useful to a fledgling country—the United States was an experiment, and portraits of the rich and powerful could be seen as proof of the success of that experiment. There is an astonishing portrait included in the book of Theodore Roosevelt standing forcefully, with his feet wide apart and his hand on a globe. This is certainly a symbol of the growing power of the U.S. at the dawn of the 20th century.

Vicki Goldberg: Very much so. It’s a portrait of Roosevelt by the Rockwood Photo Company taken in the president’s room on the Executive Office Building in 1903. It completely captured Roosevelt’s considerable ambition. He is centered between two chairs, which emphasized his central position in the scheme of things. He really appears to be confronting the camera, with his body at a slight angle. His hand is on the globe, literally manipulating the Earth. This was during the age of imperialism, and Roosevelt was at the forefront of constructing an American empire. Also, he had achieved global stature after winning the Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating an end to the Russo-Japanese war. It’s interesting to note that other presidents were photographed with globes—but the globe in Teddy Roosevelt’s office was bigger than any of the earlier globes.

David Schonauer: And you note that journalism had become big business by this point in history—newspaper readership nearly tripled between 1880 and 1909. The first White House pressroom was established while Theodore Roosevelt was president.

Vicki Goldberg: Yes, he saw a lot of people from the press standing outside in the rain one day and he felt sorry for them, so he had a little room set aside for them. But the first room in the White House especially for photographers was established under President Warren Harding in the early 1920s, I believe.

David Schonauer: Another telling picture shows President Woodrow Wilson sitting and working at a desk with his wife, Edith Wilson, standing next to him, apparently helping him.

Vicki Goldberg: Yes, and she’s looking over his shoulder. That picture was taken in 1915 and is very meaningful in retrospect. Edith Wilson was Woodrow Wilson’s second wife; his first wife had died. And she was a very close companion—she is one of the First Ladies who seems to have had a lot of influence on her husband. But what history has made of that picture is something else, because a couple of years after it was taken, when Wilson was campaigning to get the United States to join the League of Nations after World War I, he had a stroke. He was quite incapacitated, and the degree of his incapacity was kept from the public. Edith decided what business could be brought to him, which people could see him, etcetera. There were many who thought that she was running the presidency. It was very rare before this time to have a photograph in which the wife of an important man is seen working with or advising him. And here she is, working with him on what would appear to be presidential business. With hindsight, and the knowledge that she may have been doing it all herself, it changes the picture.

David Schonauer: There is a charming family portrait taken in 1924 by photographer Herbert French showing Calvin Coolidge sitting in a wicker chair with his two sons behind him.

Vicki Goldberg: Coolidge was not a great orator—he was no William Jennings Bryan—but he was lucky enough to come into office just as radio was coming in, because he did very well on the radio. But he also was conscious of his image, as presidents have been for a couple of centuries, and he wanted to show that he was a common man, which in fact he was: He did a lot of work on his father’s Vermont farm, for instance. And so in that picture he was sitting on the porch, the way everyday folks do, but he’s sitting on the porch in a suit and hat, and it’s clearly a staged picture.

David Schonauer: Moving along through the 20th century, you’ve included quite a number of images of Franklin Roosevelt, including a series of images from 1935 shot by Tom McAvoy, one of the great Time and Life magazine photographers. In these photos, which appeared in Time, FDR seems to be puffing out his cheeks, he’s working so hard at signing papers. It’s a candid look at the president.

Vicki Goldberg: It does give you a sense that the president is at work. I had a picture from around 1900 of William McKinley at his desk writing. It was pretty clear when you stopped to look at it that it was a posed picture. He wasn’t really working—he was posed to look like he was working, and this was done in part because cameras weren’t that fast then. By 1935 there were smaller and faster cameras that really did allow photographers to take candid pictures. As for Roosevelt, he was very self-confident and didn’t mind looking like he was puffing his cheeks out—he knew he looked fine. And he let Tom McAvoy do that—to show him in ways that weren’t necessarily flattering. But the pictures gave the readers of Time the sense that they could really see the president, just as his famous radio fireside chats gave listeners the sense that he was speaking directly to them. Though he came from the upper class, FDR had a really common touch with people. He was a very, very good politician.

David Schonauer: And there is a really surprising picture here—I’ve certainly never seen it—showing FDR wearing a laurel wreath and toga, surrounded by aides at what seems to be a raucous party.

Vicki Goldberg: I don’t think anyone has ever seen it, because we can’t find any place that it was published. American presidents have been criticized off an on over the years for being too magnificent in their tastes—certainly since James Madison brought French dress and French china into the White House—and FDR was much criticized for his imperial dictates. He was accused of subverting and going around Congress, and there were many who hated him for it. But he had a sense of humor, and on his 52nd birthday in 1934 he staged an imperial banquet—his staff dressed up as Vestal Virgins, whether they were virginal or not, and he put himself into a Roman toga and wore a laurel wreath. He’s clearly enjoying the whole thing immensely. It’s a very funny picture.

David Schonauer: You have a chapter titled “Cameras at the White House,” documenting the growing popularity of photography as camera technology changed in the 20th century. More and more pictures were taken in the White House, and in some cases the pictures were taken by presidents themselves. There is a photograph here of Harry Truman taking a picture of members of the White House Press Photographers Association in 1947.

Vicki Goldberg: I really love that picture. Truman signed it—“I take a picture of the One More Club—HST.”

David Schonauer: The One More Club?

Vicki Goldberg: Photographers always ask their subjects for “just one more.” One thing interesting about this picture is that you can see how the White House press corps had grown by that time, and that there are a couple of women in the group, which was something new. By 1951, there were 131 news photographers covering the White House—there was no way to avoid them. Anyway, the photographers made Truman an honorary member of their club because he took this picture.

David Schonauer: And you’ve got a picture of the famous moment in 1948 when Truman held up the Chicago Tribune with the headline “Dewey Beats Truman,” but this isn’t the shot we see most of the time. It’s from a different angle: We get to see Truman and the crowd he was showing the newspaper to. It puts the moment in context.

Vicki Goldberg: Well, you know Truman woke up in the morning to discover that he had been elected president, and that this paper, which he hated anyway, said that he had not. And at this whistle stop on the way back to Washington he held the paper up for his supporters, who were ecstatic, as we see here. There was not a newspaper in America that had predicted that Truman could win. Somebody else said about him that he was the only president who had lost in a Gallup—meaning the poll–and won in a walk. This was a great moment illustrating the relationship of the press and the presidency.

David Schonauer: Jumping forward to the Kennedy years, there is the famous 1963 Stanley Tretick photograph of John Kennedy at his desk in the Oval Office, with his son John-John peering from a trap door below.

Vicki Goldberg: You know, I purposely did not put a number of iconic pictures in the book, but I felt we needed a few, just to anchor it, and this was one of those. First of all, it’s worth knowing that Jackie Kennedy did not want her children to be swallowed by the media monster. But Jack Kennedy knew what political capital they were for him. So, especially when Jackie was out of town, he gave the press leeway to cover them. But the main reason for including it, besides the fact that it is such an adorable picture, is that I had another picture that I put in which responds to it: I discovered a picture of Caroline Kennedy visiting President Obama in 2009, taken by Pete Souza, Obama’s official White House photographer. In the photo, Caroline is standing next to Obama’s desk, which was the same desk her father had used in the White House. When she mentioned that to Obama, he went down on his knees looking for the trap door where John-John had hidden. It was locked and he couldn’t find it. Together the pictures formed such a story that I couldn’t help putting them in.

David Schonauer: Stanley Tretick was something of a Kennedy favorite wasn’t he?

Vicki Goldberg: I don’t know. Tretick was a Look magazine photographer, and I don’t know of a lot of other pictures by him. Kennedy brought the first official White House photographer in. That was Cecil Houghton.

David Schonauer: Let’s talk about the official White House press photographer. What is the role of that job?

Vicki Goldberg: The role of the White House photographer is to give the public as much of the White House as we can possibly take, and to document the history that occurs there. There had been plenty of photographers in the White House before Houghton, of course. The White House Press Photographers Association was formed around 1921. The first photographer who was given a lot of access was Frances Benjamin Johnston at the turn of the century. Then FDR had asked for somebody from the Park Service to come and photograph official occasions. That was Abbie Rowe, in 1940. Then Kennedy, who was very savvy about the media—he had the first live press conferences and the first satellite press conference—brought in Houghton, who was a member of the U.S. Army Signal Corp. I’d always thought that Lyndon Johnson’s official photographer, Yoichi Okamoto, was the first official White House photographer, but Okamoto was actually the first civilian White House photographer. Both Houghton and Okamoto were given a fair amount of leeway, though of course the president ultimately decided what could go out and what couldn’t. Okamoto was given extraordinary access. These days, it seems like there is hardly a private moment for the president. The current president even has an official videographer.

David Schonauer: You have another famous picture of President Kennedy—George Tames’s picture of the president standing at a table in the Oval Office, facing away from the camera and silhouetted by a window. The photo came to be titled “The Loneliest Job in the World,” because the president appears to literally be bent over by the weight of his responsibilities. But this is a case study of how photographs don’t always show what they seem to show.

Vicki Goldberg: Thames always said that the picture was not made to convey the president carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders. It was just that Kennedy had such a bad back he was more comfortable standing up to read—in this case, a newspaper—so while the presidency may in fact be the loneliest job in the world, that isn’t what the photo is really about. What was also interesting to me about this picture was in the way Tames was able to show the president in a rather new way. He didn’t need to show his face, because Kennedy’s figure was so familiar to the public.

David Schonauer: Now let’s skip ahead to the greatest presidential picture of all time—the 1970 photo of President Nixon with Elvis Presley, shot by Oliver F. Atkins, who was Nixon’s personal photographer.

Vicki Goldberg: That is the most requested picture from the National Archive, believe it or not.

David Schonauer: I believe it!

Vicki Goldberg: Elvis had written the president and said that he would like to join the fight against drugs, because it was a subject he knew something about. He said he also knew how to talk to young people about drugs, and he asked if he could be made a special agent of the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. One of Nixon’s aides, Dwight Chapin, passed along the request with a note that said if the president wanted to meet with some bright young people outside of government, Elvis might be the perfect person to start with. So Elvis came to the White House and had a meeting with President Nixon, and they were of course photographed together. At one point, Nixon looked at Elvis, who was wearing a black suit and a shirt with an immense collar, and said, “That’s a very interesting outfit you have on.” And Elvis said, “Mr. President, you’ve got your act, and I’ve got mine.”

David Schonauer: I want to end up with a couple of images that in a way also respond to each other. The first one isn’t well known—it shows George W. Bush sitting at his desk in the Oval Office talking on the telephone. But in this case the president is not the central point of the picture. He’s in the background, and in the foreground we see Condoleezza Rice, his National Security Advisor, standing at a window and illuminated by bright sun, but looking very, very concerned.

Vicki Goldberg: I thought that was a very fascinating picture. It was particularly interesting because the picture came to me with no caption. I was doing a chapter on portraits of presidents, and I wanted to bring it up to date. This again was an entirely new way to present a president. I thought, well that’s what has happened—the president has become so recognizable that you can publish pictures of him in which he’s in the background. And as you say, it is Condoleezza Rice who is the focus of the picture, which by the way, was taken by White House photographer Eric Draper. It was a year after I saw the picture that I finally got the full caption, including the date on which it was taken: September 12, 2001. That is, the day after the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. It puts a totally different construction on that picture, as captions often do. It’s no wonder that Rice looked so worried.

David Schonauer: The other picture I was thinking of is recent and very well known—the shot of President Obama and his senior staff in the Situation Room in the basement of the White House during the Navy Seal operation to kill Osama bin Laden. I think it’s a really fascinating picture, and like the George Bush photo we talked about, the president isn’t really the central focus of the image.

Vicki Goldberg: I agree with you—that is a really telling picture. It was a daring high point of his administration, and it’s interesting that he isn’t the focus of the picture. The focus of that picture is out of the picture…it’s the television monitor or computer screen everyone in the room is looking at. And of course what everyone talked about was Hillary Clinton, in the foreground, looking as if she is shocked or upset with whatever she is seeing. She said that in fact she was just suffering from allergies. Photographs are tricky.