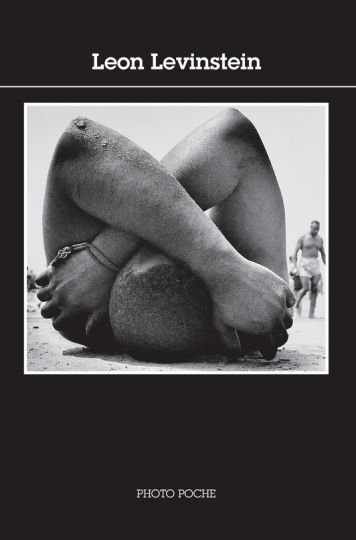

Photo Poche, the oldest and most prestigious pocket edition dedicated to photography, celebrates its 40th anniversary with a new book dedicated to Samuel Fosso and edited by Christine Barthe.

Samuel Fosso

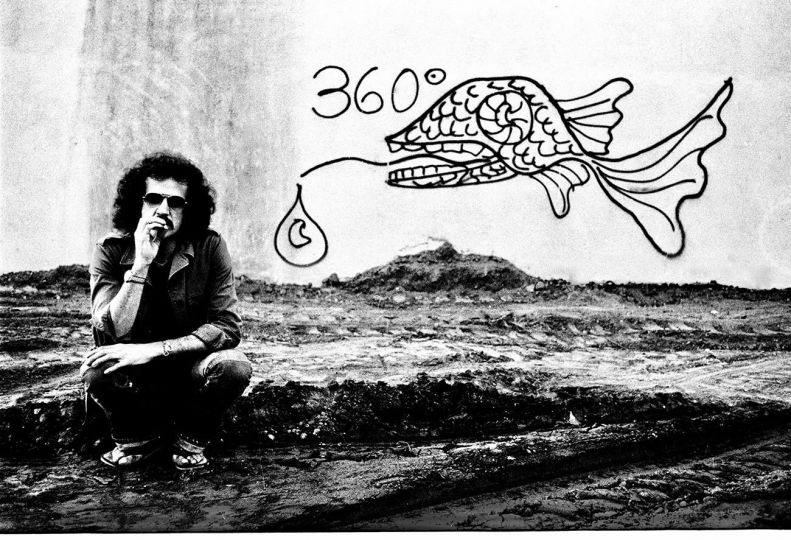

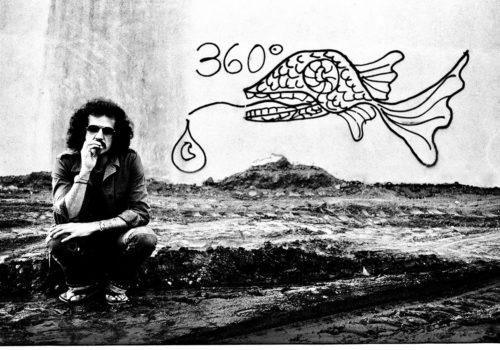

Samuel Fosso, born in 1962 in Cameroon, opened his first studio in Bangui at the age of thirteen, with the motto: “With Studio National, you will be beautiful, chic, delicate and easy to recognize.”

From the beginning, he used the last few inches of his commercial film to stage himself in iconoclastic poses and roles. His self-portraits from the 70’s Lifestyle series, initially intended for his family circle, were revealed in 1993 by photographer Bernard Descamps, who was looking for talent to exhibit at the first Rencontres photographiques de Bamako. Samuel Fosso won first prize at the festival and thus began his artistic career. Entering his work, composed of self-portraits, implies constant back and forth between the biographical and the photographic.

These two dimensions could constitute keys to reading Samuel Fosso’s images. However, this is not enough to account for the complexity of the work developed over more than forty years by this unclassifiable artist, destined to be a healer, then a shoemaker, who has been able, against all odds, to become a major figure in contemporary photography at the beginning of the 21st century.

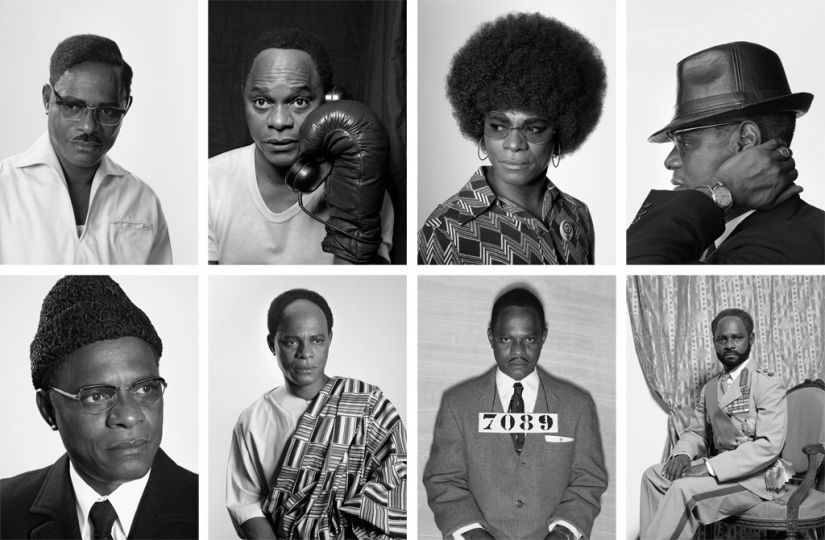

This book offers a complete retrospective of Samuel Fosso’s work, echoing the monographic exhibition dedicated to him at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in late 2021. The selection presents emblematic series in which the photographer imagines various alter egos, sometimes stereotypical (Tati, 1997), sometimes historical (African Spirits, 2008), often with a touch of satire (Emperor of Africa, 2013; Black Pope, 2017).

We also discover more intimate works, such as Mémoire d’un ami (2000), in which he questions mourning, Le Rêve de mon grand-père (2003), in which he explores the childhood he never had, or SIXSIXSIX (2015), a major piece of his recent work inspired by the painful experience of the looting of his studio.

Samuel Fosso, can you tell us about the Photo Poche collection and what, for you, differentiates it from other photo-graphy books?

One of the big differences is that the Photo Poche collection allows people who like my photos and who can’t afford to buy the exhibition catalog to discover what I do with this little book. So it’s a question of scholarship.

What does it mean to you to be published in the Photo Poche collection?

First of all, it will allow people who don’t know me or those who have heard of me to get to know me better thanks to this book that will be published soon. It will allow them to understand what I mean through photography. Sometimes people say that I am political, but I am not political, I am just showing what happened yesterday and today. It will help them understand the message I want to get across in the book.

Can you tell us about the design of your Photo Poche?

The Photo Poche was designed with Christine Barthe, a woman I know very well, who works at the Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac Museum. Together we selected these photos from different series: the one from the beginning of my career in the 1970s and the one from the mid-2000s.

How did you become a photographer?

Like many in Africa, I started photography as a commercial photographer. I started my studio on September 14, 1975 (at the age of thirteen), after apprenticing with a neighboring photographer. I didn’t go to school, but photography is a learning experience. People used to commission me to do reports at the time of ceremonies, weddings, baptisms. In the studio, people came in the evening for portraits, others for photos of their babies, they also often came in the evening. Nowadays photos are very easy to take thanks to digital technology, in those days it was different, you had to buy film, lots of film. I had a camera that took 6 x 6 films, which are square films of 12 exposures. I would use up to two or three rolls a night. And once I was done with the session, if I hadn’t completely emptied the last roll, then I would take my own picture. That’s how it all started!

What does a photography book mean to you?

First of all, like many African families, I personally did not know what is called “art”. What does a photo book represent for me? It’s like memories because there are old photos, which have become memories, and there are more recent photos, like the Pope, African Spirits… Then, a photo book is for me the opportunity to pass on a message, to let people know what we Africans have experienced, suffered. Students don’t learn these stories because everything about slavery and abuse is not mentioned in school: there is no textbook that deals with these themes. For me, it is a way, as in my exhibitions at the Musée du Quai Branly, at the Tate Gallery in London, at the MoMA in New York, to make people understand what our ancestors suffered before we were in this place today.

Christine Barthe

Christine Barthe has been scientific director of the heritage unit of the photographic collections at the Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac Museum since 2004. She has curated several exhibitions such as D’un regard l’autre, the biennial Photoquai since 2007 and most recently this exhibition entirely devoted to the contemporary image, À toi appartient le regard, a catalog published by Actes Sud in 2020.

Photo Poche – Samuel Fosso

A book edited by Christine Barthe

June, 2022

12.50 x 19.00 cm

144 pages

Price : 13,90 € for the book

Available in bookshops and on the Actes Sud website

Information

Actes Sud

Paris

October 14, 2022 to November 13, 2022