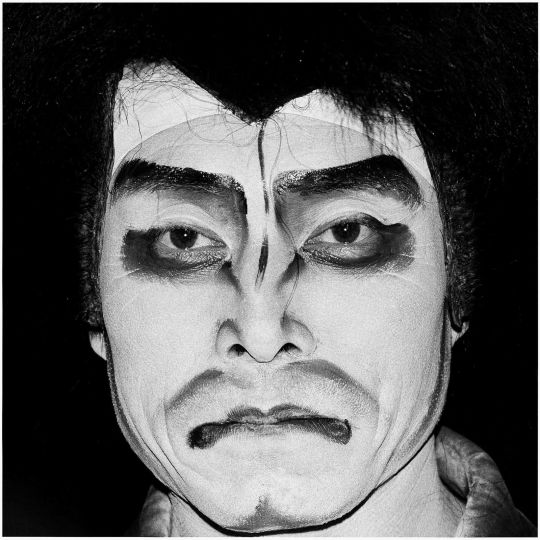

There are so many ways photographers can mess up documenting poverty. They can exoticize. They can condescend. They can skim the surface. By looking for what’s most immediately and visually telling, moreover, they can miss what’s human—and heartbreaking—entirely.

Eugene Richards, a documentary photographer who’s spent more than four decades investigating race, inequality and class, approached that tricky territory in the late 1980s, when he traveled to 11 states to spent time with poor families for what would become a book, Below the Line. His photographs took readers from farms to inner cities, from Massachusetts to Wyoming. In so doing, they underscored the depth of a problem more widely and universally experienced than anyone—Richards’ critics especially—would have liked to believe.

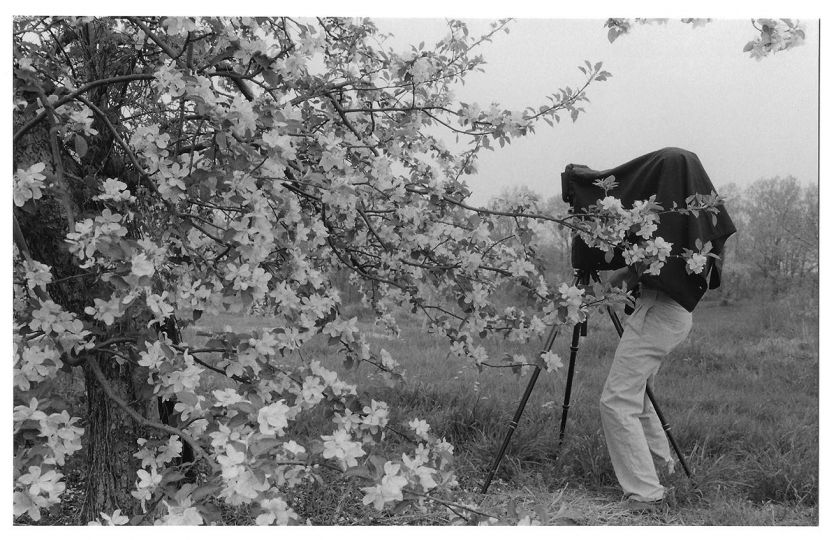

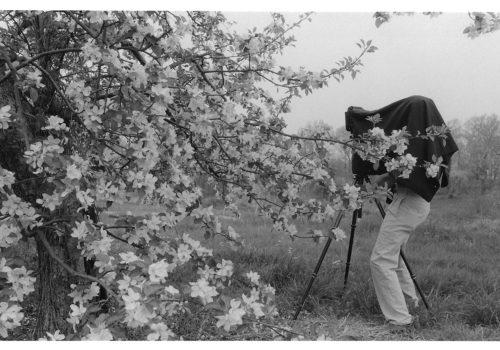

Where lesser photographers have failed, Richards emphatically succeeded. Instead of gawking, he carefully looked. Instead of simply searching for something to say, he listened. It’s these qualities, Bronx Documentary Center (B.D.C.) co-founder Michael Kamber told me that make Richards “the greatest living documentary photographer.” The B.D.C.’s exhibition, “Below the Line: Living Poor in America by Eugene Richards,” on view through November 6, 2016, is proof of Kamber’s point. It comprises a selection from Richards’ seminal book, along with a more recent video he made about life in the Arkansas delta.

Richards, surely, is a master of composition and lighting, but even his least striking black-and-white photos in Below the Line are leant extraordinary power when paired with the personal narratives of some of the people he depicts. Take, for instance, his photo of Connie Arthur, sitting on the floor as she stocks shelves at a Wyoming Safeway. It’s a perfectly good, yet unremarkable photo, but without her adjacent testimony, we’d lack the context that makes it such an important image.

Without that text, we’d have no way of knowing that by the time she got to the Safeway at 4 a.m. that morning, Connie had already braved the icy morning roads to deliver the local newspaper. Likewise, we’d have no way of knowing that, after this photo was taken, during her lunch break, she’d have to go deliver another newspaper, and that, when her shift at Safeway was done, she’d have to go to a Country Inn to clean for even more hours. Moreover, we’d have no way of knowing that after all this work, Connie would still only bring in $13,000 a year—not enough to support her family’s modest lifestyle.

How, Richards forces us to ask, can a woman in the world’s richest country work so hard, and yet lack so much? How can people keep touting the American Dream when it is such a maddeningly obvious fantasy? While Richards’ photos are frequently quiet and somber, it is hard not to look at the unfairness underlying them with anything other than anger.

Richards’ photos resonate so strongly in 2016, in one respect, because they depict an experience that’s still so widespread. Indeed, more than 45 million people live in poverty in the United States today. In Melrose, the neighborhood where the B.D.C. makes its home, nearly half the residents are poor. All told, there are millions more Americans in poverty now than when Richards published his 1987 book.

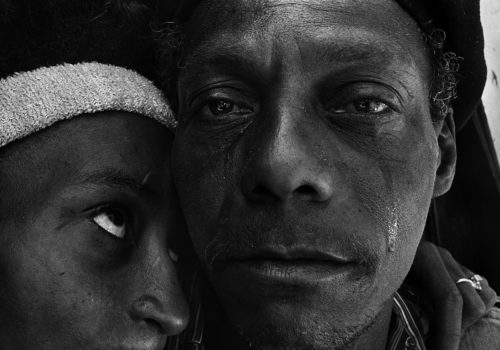

Still, it’s worth emphasizing that Richards’ show isn’t just a story of doom and gloom. While Richards’ soberly and forcefully condemn the injustice of poverty, they also, crucially, present a well-rounded and humanizing portrait of the lives of poor people.

It would be a mistake to miss that Richards’ photos show moments of joy and tenderness. I think of the look of wonder in the eyes of a group of kids and adults in Still House Hollow, Tennessee, as they observe a lit firework held aloft in the dark night. I think of Shockey, 13 years old and pregnant, who Richards has photographed being gently kissed on the back of her head by a young man. And I think of Francisco Gonzalez, who’s seen holding on to the sick and elderly Emily Chung, the widow of a kind laundryman who gave him a place to stay.

“Beyond The Line,” of course, can’t change the circumstances it depicts. But it can, reinforce the simple but too-often forgotten fact that poor people experience not just misfortune and sorrow, but laughter and love and levity. That’s a timeless truth endlessly worth sharing.

Jordan G. Teicher

Jordan G. Teicher is an American journalist and critic based in Brooklyn, New York.

Eugene Richards, Below the Line: Living Poor in America

October 1 to November 6, 2016

At Bronx Documentary Center

614 Courtlandt Avenue

Bronx, New York 10451