There is a vigorous, sustaining solidity in Errol Sawyer’s photography—as you visually regard his work, you will see a consciousness that is vital to the moment’s reality. With more than forty-five years of photography travelling through his eyes, he independently explains through paused moments truths that are more about his strengths than about what you may catch a glimpse of on the surface.

You won’t see articles about Errol Sawyer from the educated scholars and experts on blacks photographers, from such writers as Deborah Willis or Maurice Berger. Yet, his work spans into and participated in that glorious period in commercial, fashion, street, and experimental photography that stretched from the 1970s to the 1990’s. It is what I refer to as, the final sprint of the 20th century: Simply, good photography. This lack of acknowledgement from these experts and their dedication to covering Black Photographers (historically and modernly) reminds us that as a modern society we, as readers and lovers of Art, have to travel beyond what is promoted in the mainstream circles of Photography & Art.

During the 1970s Errol Sawyer’s photography that was commercially on target: stunning composition, au fait lighting of the model or products, and the overall general significance that every successful fashion or commercial photograph is designed to attain – selling the message to the consumer, this idea of looking great like this photograph; it could be you wearing this or looking like that model.

Errol Sawyer comes from a period in Photography when fashion photography was an outlet for the serious photographer, who would see the commercial world as a way to gain some income. In order to create their own personal projects, they co-mingled with a commercial world and its one-way (sometimes narrow) standards of what was beautiful when it came to the models or what was in style with a brand name fashion house. Richard Avedon, Edward Steichen, Irving Penn, Diane Arbus, Robert Frank and other artists were all clever enough to know that the leverage of a commercial paycheck could be a gateway for them to get their true vision across in personal photography projects that had absolutely nothing to do with pleasing a commercial audience. It was the balance in such an understanding (knowing the difference between commercial work and personal work) that put them into the category of evolving as artists, within a medium called Photography.

“A photograph, or any image for that matter, should not only articulate a point in time and space, but simultaneously provoke a re-evaluation of that particular point,” said Errol Sawyer. “It should stimulate our perception of what we take for granted about physical phenomena. That’s why it is so important to leave a picture as it is and that is why I work as an analog photographer. Following development and evaluation in my darkroom, I often appreciate the presence of an alternate dimension or force just beneath the surface of the primary image. It seems to be constantly unfolding, inviting different interpretations.”

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, editors of high fashion magazines would allow the photographers to have some visual freedom to make the photograph. Unlike today, where editors of high fashion magazines can easily see the photograph as a disposable task (A, B, C, he, she, or they could take a photograph – there are many fashion photographers out there) which condones the comforts in commercialism and how the industry can control the photographer or else he or she can be replaced by other photographers willing to abandon their creative freedom for the paycheck & modern fame that can make a photographer into a brand.

Errol Sawyer is from the status era of photography, when there was no such thing as a fashion photographer – you either were a photographer or not a photographer. This is why his commercial work could sit next to Richard Avedon’s, Irving Penn’s or David Bailey’s photographic works. From French Elle to U.S. and French Vogue, his work was always about visual intelligence. As a Black man, his photographic successes with these mainstream fashion magazines were pioneering. Just as Gordon Parks laid out ways for a Black man to show his visual skills with photography in Vogue & Life magazines, or Roy DeCarava injected his intense photography out into the world, Errol Sawyer’s presence in Photography should be held up just as mighty and confident as when we hear of those John Coltrane photographs from Roy or those Life Magazine photographs that followed societal essays from Gordon.

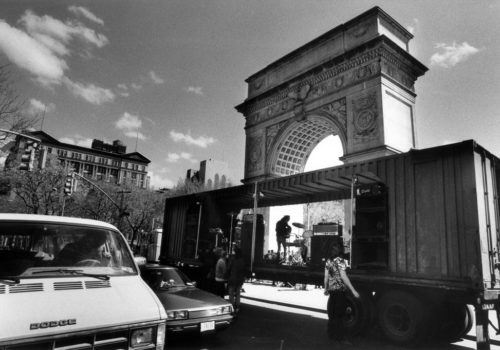

His street photography reeks of the moment being true, and not in the sense of shock-value, but in the channel of seeing the Moment extract itself into a visual memory. Errol Sawyer’s street photography cradles composition. The angles are ambitious, while what spreads across the frame is uniquely open to attending to his way of seeing Life. How he shapes light with his black and white photography is something that belongs to knowing his film photography. Even though the visitor to his photographs can see that he has a professional hint of knowing what he is doing, photographically, the freewheeling flow of his street photography goes right back to his startup days as a photographer, as he once held a Kowa camera in South America during the early 1970s.

City Mosaic is an important book of work from Errol Sawyer. The book opens with a dedication to his son, Victor. From there, it is a collection of his street photography that has well-written and in-depth introductions by prominent art critic/writer, A.D. Coleman; Professor Dr. Franziska Bollerey; Errol Sawyer’s wife, architect Mathilde Fischer. City Mosaic does not center itself squarely on photographing the Moments of life, with either a person or a group of people filling up the frame. Errol Sawyer knows how to see the symbolism in worn out signage that is beyond literature to a photographer such as himself. The streets became his library. From the image of the man feeding the bird with his hand, as the shutter speed freezes the bird in flight, Errol Sawyer has photographed humanity. Contrast this frame to another photograph found in City Mosaic: a shattered window that has the word, “Change” right next to it – Errol Sawyer has photographed a cycle in life. At times, it may take the shattering to teach us the lesson that can shape a philosophy in changing how we see, think, eat, love, rise through anger and frustration for the cause of understanding happiness & peacefulness; therefore continuing to live with ourselves, with a sense of wanting to know ourselves. City Mosaic offers three chapters of 64 black and white photographs, that refuses to let go of the expectation of visually needing to see more substance.

Does Errol Sawyer’s work in City Mosaic become philosophical or does it become Street Art? The benefit that falls out of City Mosaic and into your awareness, is that he always gives the onlooker a choice. Which, when measured up against our modern world’s profusion of photographs being thrown into our society, is rare to encounter with visual imagery; he is sharing the concept of freedom with you, to think for yourselves. To turn each physical page and grasp the full frame of his incisive black and white photographs, which are so indifferent to the glossy, color, (but very good) fashion & commercial photography that he put out into the consumer world.

Errol Sawyer’s work outside of commercial photography elects itself into a photographer becoming more than just the visual ticket to sell something to the consumers. This outside of commercial photography work respires an individuality finding its definitive visual abilities. His work could be neatly debated against and freed with the outside of the commercialism boxes that Nathan Lyons, Val Telberg, Lucas Samaras and Anselm Kiefer jogged away from. With a marathon in their minds that their photographic works could travel over and beyond the surface attractiveness that a photograph can govern with, when the onlooker is drawn to photography because it is a commodity for society’s interest – these photographers wanted the onlooker’s intellect to vote for its own way of seeing a truth inside of thinking for yourself while being a citizen to the outside of the box photography. Photographers such as Errol welcomes the onlooker to become revolutionary in opening up their minds, even if they arrived from a past that once felt the conditioned comforts of commercially correct photography.

“My work is informed by my early experience as an African-American native New Yorker in the Balkanized bosom of first and second generation working class Jewish, Italian, Irish, Polish, Czechoslovakian and Puerto Rican communities of the East Bronx, New York,” said Errol Sawyer. “Aesthetically, my work continues the conversation initiated by African Modernists, Dada, Kurt Schwitters, Aaron Siskind, William Klein, Jackson Pollack, Roy De Cavera, Henri Guedon, Henry Miller, Miro, Picasso, Miles Davis, Jimi Hendrix, Santana, Stanley Clarke, Chick Correa, Tito Puente, Los Pepines et al. Graffiti has been with us since men lived in caves. Affiches and Graffiti are both transformations as they reflect what people have done to them as a collective form of expression. They show the perpetual change.”

With photography exhibitions that have been held in honor of his photographic works in New York, England, Switzerland, France, Netherlands and Sweden, the cultural outcomes of his photography have met with praise and well-deserved acknowledgements. When you have photographic collections that have adorned the walls of the Tate London, La Bibliothèque Nationale (Paris) and the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York’s Harlem, your body of work enriches itself into an arrangement that fits into the corner of Photography having an artistic say-so within its capacity of being a visual medium.

Some photographers will end up betraying themselves. The circumstances of betrayal could be about success, fame, being burnt out, or just finding that the business world of photography does not always want to be married to the artistic mentality. Errol Sawyer has found his own way to stay connected to this medium (Photography), and he has refused to distance his eye from his values. He owns up to his photographic work! The man does not have to do any kind of photography to prove anything to some young, famous photographer with a massive online following. For someone to give forty-five plus years of his life to this medium and see the 21st century of photography become a conduit for popular photography over good and great photography; the fact that Errol Sawyer has not betrayed himself to fit in, along with how he can visually see the parameters within a Moment, have contributed to his years of teaching Photography in the Netherlands, at Technical University Delft, 2006-2010; thus, giving back to the future eyes in Photography. All of this is about his fortitude to refuse to distance himself from Photography.

To decipher how a man who has witnessed Photography grow beyond his personal desires, successes and accomplishments, not only as a Black man pioneering his way through a commercially, white mainstream world of publications and products, is about an inner quality that continues along the path of an ardently heartfelt vision. To see that his eye has matured in a way that has continually ascended into Errol Sawyer’s honesty as a photographer, is something that requires willpower. This goes beyond the changing times in high technology. If anything, his photography clarifies how he has stayed true to his eye. He found his honesty through Photography and what you meet is a photographer who is always learning, but always willing to give back, photographically and honestly to the realms of a visual life.

Shaun La

Shaun La is a photographer and writer living in New York, USA.

To learn more about Errol Sawyer’s photography or to order photographic prints or book-work, please feel free to contact him by visiting his official website at: