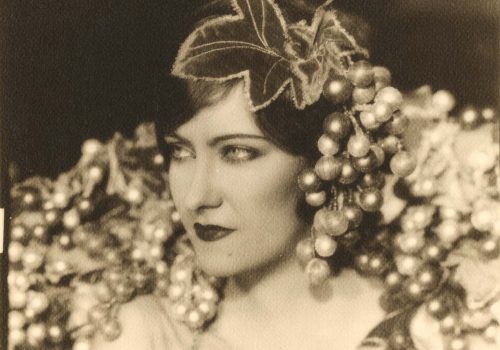

Only Ernest Bachrach at Radio Keith Orpheum had a career at one studio that rivalled Clarence Bull’s tenure at MGM. He joined RKO at its inception in 1929 and stayed until Desilu purchased the studio in 1958. Before coming to RKO, Bachrach worked in New York for Famous Players-Lasky. In the mid 1920s Famous Players-Lasky was consolidated with parent Paramount Pictures and production was moved to Los Angeles. Bachrach worked independently for a short period and photographed many of the silent beauties including Mae Murray and Gloria Swanson. According to Bob Coburn who during the 1930s assisted Bachrach in the RKO portrait studio, “Gloria [Swanson] thought he was the only photographer in the world and when she came back out here to work, he came with her.” His portraits of Swanson testify to her feelings about the quality of his work. “Bachrach was an all-around man,” Coburn told Kobal, “he could do anything photographic.”

Katharine Hepburn was signed by RKO in 1932 and made fourteen films including Bringing Up Baby (1938) before she was dropped as “box office poison” six years later. Bachrach made nearly all of Hepburn’s portraits during this period and turned her angular, slightly androgynous and freckled face into an archetype of 1930s glamour. Bachrach’s transformation of Hepburn’s face and the subtlety through which he photographed her through films as different as Christopher Strong (1933) and Spitfire (1934) is rivaled by the range of Hurrell’s work with Joan Crawford. “I used to pose a lot for Bachrach.” Hepburn told Kobal. “I enjoyed it. The results amused me. He liked me, he liked to photograph me, and I enjoyed it. He was an awfully good photographer although I don’t think the studio thought anything about it.”

Beauties such as Carole Lombard, Michele Morgan, and Betty Grable were also well served by Bachrach’s camera when they worked at RKO. Lombard was under contract to Paramount during most of the 1930s before coming to RKO in 1939 where she made four films over two years. Coburn remembered that working with Lombard at RKO was “fun and games. And she really knew what to do, she knew the techniques, where the lights went. She knew nothing would be wrong if I shot her. And they all knew you wouldn’t let their bad points show. They trusted you.”

Like Clarence Bull, Bachrach worked through the 1950s giving him the chance to photograph a new generation of stars like Marilyn Monroe and Clint Eastwood. With Monroe he managed to make an artfully contrived photograph seem as spontaneous as a snapshot. Eastwood, photographed in 1956 before he had been noticed by the public, preens before Bachrach’s camera revealing a side to the actor which is startlingly at odds with his later persona.