In the words of the art critic Philippe Dagen, “Émeric Lhuisset is a kind of artist we haven’t seen in a dozen years . . . . For lack of a better word, he could be compared to artists historians.” To tackle the strategic question of water in the Middle East—a region Lhuisset is well familiar with, since he has worked there for 13 years—and particularly in Iraq, the artist has combined the climatic, geo-political, historical, and aesthetic perspectives. “I started reflecting on this issue and realized that all the factors were coming together for a water conflict to break out,” Lhuisset explained.

At the local level, these factors include ethnic and religious tensions combined with the presence of militia, who are extremely difficult to control but essential to the fight against ISIS, alongside a steady population growth. At the regional level, the dependence on the two rivers enclosing the region, and lending it the name of Mesopotamia, have turned the Turkish land and water development project (GAP) into a major challenge to international cooperation. Lastly, at the global level, climate change entails a drop in water levels and an increase in salt content in farmlands. In medium term, population displacements are inevitable, resulting in a volatile mix of Shiite and Sunni communities in Iraq, setting off a possible conflict.

“How does one talk about a conflict that hasn’t happened and may never happen?,” asks Lhuisset. “I looked into the past and based my observations on the only water war in the history of humanity, which took place 4,500 years ago in the south of today’s Iraq and was waged between two city states: Umma and Lagash (today Girsu).”

Lhuisset captures the minimalism of this arid, monochrome desert, with few discernible vestiges of human activity: a pile of bricks one could easily mistake for rocks, eroded and scarred by salt. Whether aerial, cartographic views or ground-level shots, his photographs have a primitive feel. Although they are nothing like the codified images of the theatre of an imminent war—unless we include in this category the work of Fazal Sheikh in Israel and Palestine—Lhuisset’s photographs similarly offer cold, metaphoric evidence of a catastrophe. “There are mounds which appear constructed, but are not. The only traces one can see are those left by water and erosion,” he describes.

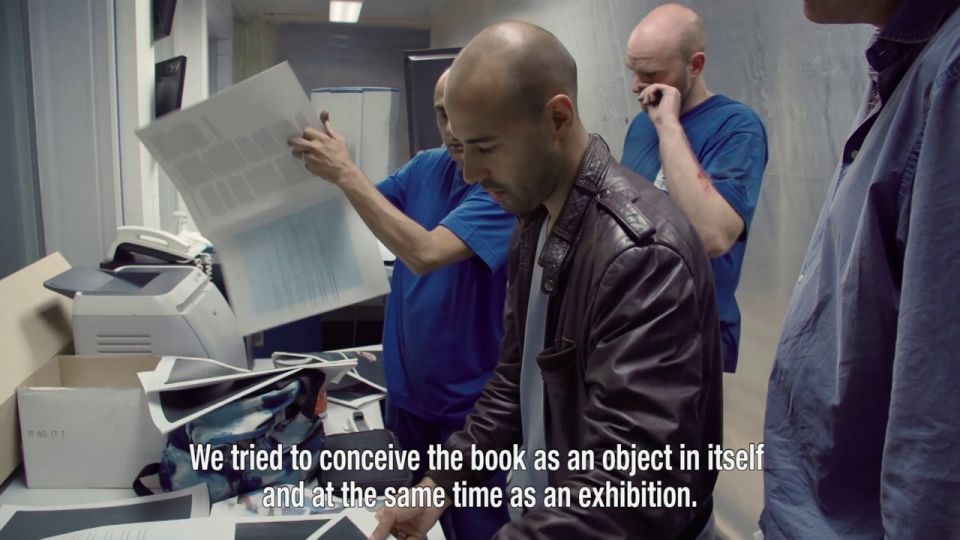

The same holds true of images made using drones, where the point of view makes one lose a sense of both scale and time. “Between the ruins and the water, the silt holds memories of cries and flames. The river flows today beneath a closed-eyed citadel. It flows towards Peshkhabour, a crossing point between two imaginary countries delimited by the river and the arsenal of riverside dwellers,” Le Monde journalist Allan Kaval writes in the introduction to his book published by André Frère.

The exhibition at the Institut du Monde Arabe adds a few clues, notably thanks to two types of videos. One type, shot using drones, foregrounds the effect of images. The other points toward something more concrete, through testimonies of residents of Iraq’s deep south who already feel the impact of aridfication. Combining two different temporalities—ancient and contemporary—the project reports on the ephemeral character of any civilization. “It shows the fragility of our surroundings,” concludes Lhuisset.

Laurence Cornet

Laurence Cornet is a journalist specialized in photography and an independent exhibition curator based in New York.

Émeric Lhuisset, Last water war, ruins of a future

Until December 4, 2016

Institut du Monde Arabe

1 Rue des Fossés Saint-Bernard

75005 Paris

France