The modern modeling industry was born in 1923, when John Robert Powers, a resting Shakespearean actor who had started posing for freelance fashion shots, published his first photo catalogue of some forty male and female “models,” with full descriptions and precise body measurements, then set up the offices of the John Robert Powers Modeling Agency in an old brownstone over a speakeasy off Broadway.

Beauty was starting to become big business in the years after World War I – the tenth-largest U.S. commercial category, in fact, during the 1920s. Retail sales of cosmetics and toiletries reached $378 million in 1929, and as both advertising and editorial coverage expanded, so the market for modeling grew. In 1930 another “resting actor”, Walter Thornton, founded his own modeling agency, a matter of months following the Wall Street crash.

As proud of his Shakespearean knowledge as John Robert Powers, Thornton took to describing himself as the “Merchant of Venus” on the strength of discovering the sultry Betty Perske in a Greenwich Village beauty contest and re-launching her as Lauren Bacall, then pulling off the same trick for Edythe Marrenner of Brooklyn—Susan Hayward. It was small wonder that would-be models beat a path to his door, and one day in 1938 a starry-eyed hopeful from Great Neck, Long Island, presented herself at Thornton’s plush office on Lexington Avenue, its walls covered with photos of well-known models and film stars.

“A sixteen-year- old heart began to pound with excitement,” she later wrote, “as the agent glowingly sketched the career he envisioned for the girl. Magazine covers and screen tests were practically assured within six months! She would, of course, have to spend the insignificant amount of $60 to have photographs taken, but the money would be made up in a day or two. The girl could hardly wait until she arrived home to tell her parents of the fairy tale that was about to come true.”

The fairy tale never happened, of course. The Merchant of Venus extracted a further forty dollars for prints of the nondescript test shots of the teenager—“then promptly forgot,” she later recalled, “that I ever existed. He never booked me for one single modeling job, and looking at the picture, I am not surprised. I had a nice, pert nose but a plain round face and a mop of curly brown hair. That was not the photograph of a successful model.”

Eileen Otte Ford was able to be as brutally honest about herself, the starry-eyed wannabe from Great Neck, Long Island, as she would later prove to be about the thousands of young women she would assess – and usually reject – in her long career as a model agent. But her painful first contact with the fashion business did teach her a valuable lesson. When it came to money and modeling, it clearly made more sense to be behind the camera than in front of it. And it took nearly two years for her to venture near a model agency again.

“I remember that I met Jean Compo on my very first day at Barnard College—on September 21, 1939,” Eileen related while talking to her biographer, Robert Lacey, in 2010. “She asked me the way to the bookshop. So I walked her over, and we became fast friends.” Compo was a stunningly beautiful blonde with a pageboy hairstyle with straight-across bangs. From the start of her studies at Barnard, sister college to Columbia University in New York, she had been earning extra money as a spare-time young model for the recently created Harry Conover agency, so when she heard of Eileen’s unhappy experience with Walter Thornton, she persuaded her friend to try her hand at modeling again. Conover, she assured Eileen, was different.

Harry Conover was the hot new name in New York modeling at the end of the 1930s. Six feet tall, green-eyed, and wavy-haired, Conover had started as a model himself with the John Robert Powers agency, then defected in 1937 with his handsome flat mate and fellow Powers model, Gerald Rudolph “Jerry” Ford, Jr., the future Michigan congressman, vice president to Richard Nixon, and eventually U.S. president, who became co-owner of the Conover agency for a few years. Like Walter Thornton, Conover liked to give his “Conover Cover Girls” exotic new identities, but in a slightly different style, devising coquettish nicknames to go with their otherwise routine surnames—“Chili” Williams, “Jinx” Falkenburg, “Dulcet” Tone, and “Frosty” Webb.

When Jean Campo brought Eileen Otte to Powers’s office at the start of her 1940 summer vacation, Conover could see she was no glamour-puss, but one of his skills was to pick out the “natural” or “authentic” face that advertisers sometimes preferred over stagier beauty. Eileen was a fresh-faced college girl, pert and eager, with an uplifted ski jump of a nose. As such, she filled a perfect short-term niche. Every summer Mademoiselle magazine ran a “college” issue to preview youthful fashions for the fall. Professional fashion models were remote and aspirational figures—fantasies, at the end of the day. College girls were a step closer to reality, and Eileen certainly looked like the girl next door. So Conover booked photo sessions with her for the advertising and editorial sections of Mademoiselle’s special issue.

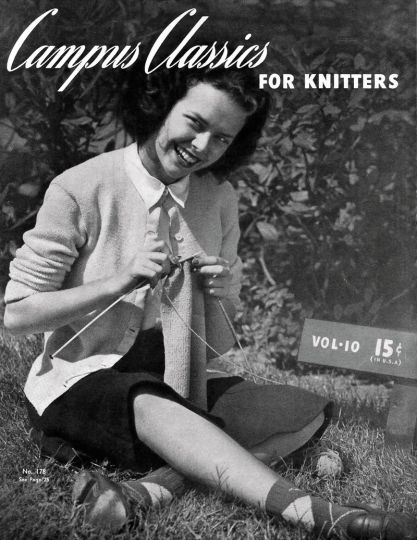

It was unfortunate that Eileen Otte’s moment of glory, her sole appearance on an editorial page, was mis-captioned: she was labeled as “Helen Otte” on page 170 of the college issue for August 1940, which described her as “the brightest sophomore on her campus in Stroock’s fleece-cloth reversible . . . $39.95, Lord & Taylor.” But later that year she became a cover girl, featured on the outside of Campus Classics for Knitters booklet for October 1940 with a dazzlingly wide smile that revealed an evenly balanced array of handsome teeth. As well as appearing on the cover, Eileen was depicted on the inside pages, parked cheerily on a stone doorstep in Heidi-style socks, holding a pair of ice skates.

“The skates were the reason why I got the job,” she recalled. “I was the only person at the agency who owned a pair. I signed up with Conover again for the summer of 1941, and he got me still more work.”

Once again Eileen featured in a range of college girl shots in the pages of Mademoiselle: she advertised a collection of dressy undergraduate outfits for Saks At 34th Street, and also appeared in the hallowed pages of Vogue, advertising Enka rayon and also SporTimer dresses—“To See Them Is to Want Them!” The highlight of her modeling career was her appearance that September on the cover of Liberty, the “Weekly for Everybody,” which prefaced each of its articles with its famous “Reading Time” prediction—an estimate of the time that each article would take to read, down to the second. A diminutive Eileen gazed up admiringly at a huge, muscular Cornell Big Red football player, above the cover line “They Had Magic Then! A Short Story by Sinclair Lewis.”

Looking back on her modeling career from her eminence as a successful agent, Eileen could not remember the details of her final college-era photo session as a mannequin, but she could recall one very important upshot: “Conover never paid me a penny for all the sessions that he booked for me.” Might there be a niche in the world of modeling for an agency that actually treated its models decently?

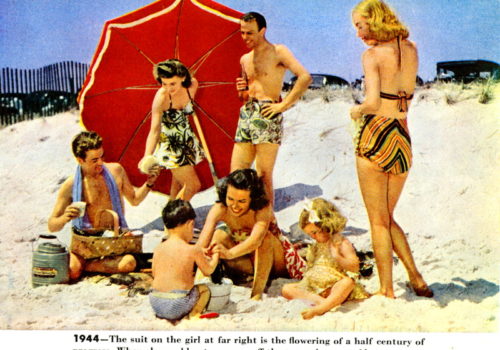

In the summer of 1944 Eileen Otte met her future husband Jerry Ford and embarked on the career path that would lead to her creation with Jerry of the Ford Modeling Agency. It had started not far from her Long Island home. Lying on a towel on Jones Beach, Eileen was engaged in one of her favorite activities: perfecting her tan.

“I had just finished a hot dog, when this charming photographer came up to me. He said he was called Elliot Clarke and that he was shooting a magazine feature on the history of bathing costumes. Would I care to pose, he asked me, in a historic bathing costume?”

Just one? Eileen jumped up and put one hand to her ear and the other to her hip to present herself as the perfect 1910 “bloomer girl.” Then she put on a black-and-white spotted “dressmaker suit” from 1922 and waded out into the surf to show what a bathing belle looked like in the year of her birth. With her animated features and wide, toothy smile, Eileen made herself the star of the quirky color feature that Elliot Clarke put together on Jones Beach that day, completing her poses in a modern (1944) swimsuit with children and other bathers gathered around a picnic basket in a family tableau worthy of Norman Rockwell.

The photographs appeared in the August 5, 1944, Saturday Evening Post magazine, under the headline “Yes, My Daring Daughter.” They hardly prompted a flood of phone calls from modeling agencies. In fact, the session with Clarke would be the last one in Eileen’s relatively modest career in front of the camera. Yet it did prove a crucial step in her progress to a historic and groundbreaking career on the other side of the lens.

Robert Lacey

Robert Lacey, Model Woman: Eileen Ford and the Business of Beauty

Published by Harper

$29,99

ISBN: 9780062108074