Through December 3rd, Jackson Fine Art, in Atlanta, presents an exhibition by American photographer Duane Michals entitled The Narrative Photograph. Portrait of a lover of stories and dreams.

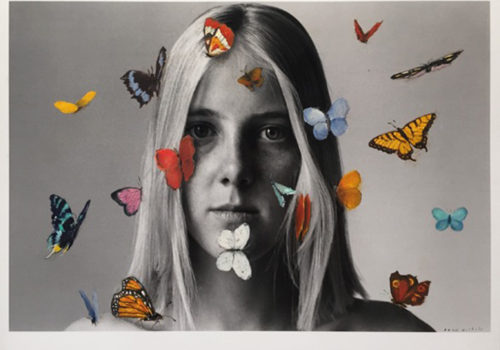

Working, teaching, chatting or just living: whatever he’s doing, Duane Michals is a man with a big heart—which has always made him a photographer unlike any other, totally committed to authenticity and the extraordinary. Love of the imaginative, love of whimsy, humanity, knowledge, curiosity, and humor: now eighty-one, this child of a hardscrabble family from McKeesport, Pennsylvania, seems to have inherited a state of mind like no other, a unique blend of absolute intellectual freedom and the omnipotence of dreams. There’s no resisting his vehemence—his bulwark against facility—or the mockery that shields a humility success has never compromised. He wields provocation like a schoolkid dealing with a teacher, laughing at the world and other people, but never contemptuously: just mischievously, throwing down the gauntlet to the rules and regulations. “Doctor Duanus”, as he likes to call himself, combines a gentle gaze and a muted voice with a fondness for plain talk. He uses words to accompany his wonderment at simple things: and the result is a poetry of the everyday that segues into a theater of the fantastic when, to add a touch of romance, he mutates into a street clown or an actor in a drama. It’s almost as if the atmosphere of Georges Méliès’ films were back, and with it a hankering for tales of the marvelous. There’s a part of Duane Michals that is neither photographer or artist—words all but banished from his vocabulary—but something else: a being beyond all pigeonholing, a kind of kid-style magician.

To get a handle on Duane Michals, we have to go back to the Depression America eloquently captured by photographer Dorothea Lange. When he was born in 1932 in McKeesport, once a thriving steel town whose population was being driven into forced exile, his future seemed written in stone: a factory job, like his father, uncles and grandfather before him. Although his parents—a “married couple who never really loved each other”, he thinks—did not pressure him in that direction. And the family home was not little Duane’s favorite place: “There was always a lack of warmth,” he recalls, “especially between my father and me.”Marked by years of poverty, he saw himself as a voyager: “I understood pretty soon that I wasn’t made for McKeesport. The town was never a destination for me, it was a place to get away from. When I was still pretty young I learnt to take risks and trust my imagination. I always told myself I’d go to New York and have great adventures there. Nothing but adventures. Even today adventure is the only thing I really believe in.”

The ruins of his childhood home are still there in McKeesport, bricks and wood worn down by time like the rest of the city; you can see it in Frenchman Camille Guichard’s documentary The Man Who Invented Himself, released in November 2013. Duane returned there for the film, and against a backdrop of abandoned hovels he reminisces and conjures up his fictional neighbors of the time: Madame Bovary, “who flirted with my father”, and Jane Austen’s mythic Mr Darcy, with whom he shared “tea and cucumber sandwiches.” At night he took all his famous friends for a walk to the lighthouse on top of the nearby hill, a lighthouse “with a thousand steps. On a clear night you could see the twinkling of the Eiffel Tower. . . but all that’s gone now.”

Some of Duane Michals’ dreams were left behind in McKeesport, but as he had foreseen, his personal legend got written in New York. A stone’s throw from Union Square, the light-filled apartment he bought in 1965 is full of other timeless memories. It’s here that he has thought up and taken most of his photos; and with its atmosphere that suddenly takes you back into the last century, this place seems imbued with a consciousness of its own. Among the plants are the works of creative people he admires, like Balthus, René Magritte and André Kertész. Sometimes they’re an aid to sleep, like Paolo Ventura’s photo of a drowsing Harlequin hung next to his bed. Often they’re bits of everyday inspiration like the little book open on a music stand, an 1820 collection of mangas whose pages he turns from time to time so as to enjoy “a never-ending exhibition.” Sitting in state on a small table nearby are two black and white photos: one of his father and the other of Duane with Tillie Bush, daughter of a Mormon family, met when he was at art school in Denver. “That was before I faced up to my homosexuality,” he reveals. “You know, the Mormons believe in all sorts of crazy stuff. And after a few weeks she wanted to get married. Can you imagine that?”

For fifty-three years now Michals has been sharing his life with Fred Gorree, a former architect. Fred, who has Parkinson’s Disease, “still makes me laugh a lot, and makes me worry even more.” He’s at Duane’s side at all times, with a nursing aide. Working away on this August afternoon, Duane keeps a tender eye on him, like someone with a child who’s learning to walk: “It’s the cycle of life. When you get old you go back to the wellsprings of existence.” There’s classical music playing loud as Duane, brush in hand, puts the final touches to a piece from his new series Famous French Writers (2013), commissioned by the Esther Woerdehoff Gallery in Paris. Some of them are now on view at Jackson Fine Art. These are anonymous photos retouched with oil paint, imaginary portraits of his favorite French men of letters: Sartre, Proust, Apollinaire, Voltaire, Genet. A mix of black and white images and colored paint, born out of a simple urge to “satisfy his curiosity” putting the two together. “Green or blue? What do you think? No, let’s go for red, it’ll put more life into it.” Nothing’s finished yet, but in the context of the Michals oeuvre this series strikes you as something new—or rather a return to his first love for this “failed painter.”

The realm of the imaginary

Duane Michals has never studied photography, which is probably why he’s never shown any inhibitions regarding the medium; never drawn on any other oeuvre or major artist, to the point, even, of damning the established traditions. When he started out in the late 1950s, he saw images as a way of expressing ideas, as a vision of the world or of existence. So his work has to be approached like that of a writer or a philosopher who uses aspects of reality to speculate about and depict what can only be imagined. This is photography of the thought process. “I’m lucky,” he says. “I’ve had the chance to turn all my life experiences into art. I’ve hardly ever used my camera to look into someone else’s life or experience. It’s never crossed my mind to go to Harlem and photography the black community there, like Bruce Davidson, my contemporary. In this sense I’m more a short story writer than a photographer.”

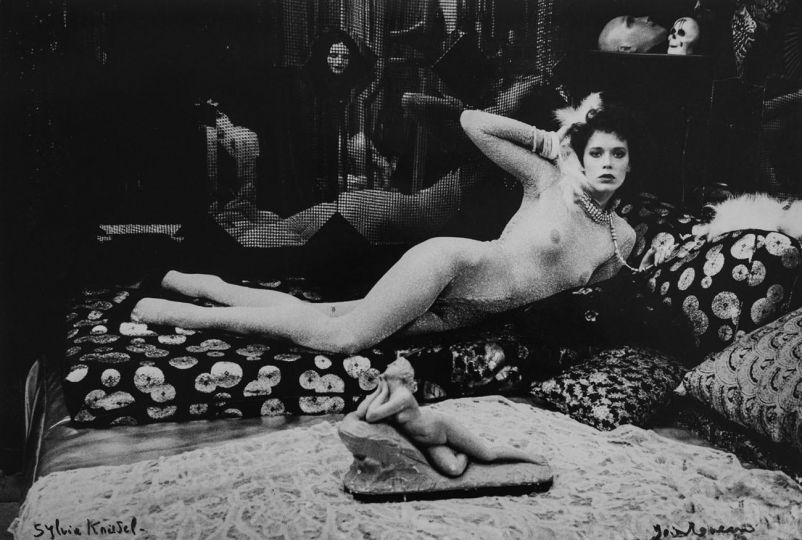

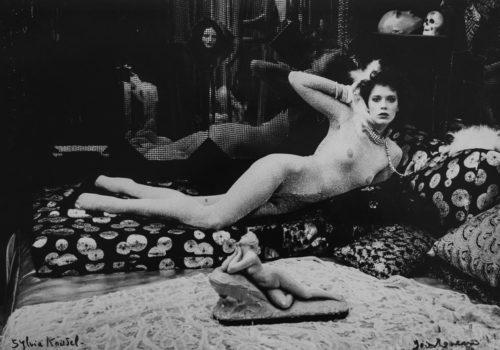

Even so, the first time he ever used a camera was in 1958, when he was in Russia, which had just opened up to Westerners: he photographed sailors, children, circus performers—portraits we associate with the documentary label he would detest seeing applied to this work. Back in New York he took a few commissions, mostly commercial, but his real interest was painting, and the Surrealists in particular. Balthus, Magritte, and Giorgio De Chirico were—and still are— his favorites: he loves their theatricality and mystery, their use of the unconscious, their play on duality, and above all their freedom of spirit. His first encounter with them came at MoMA, where he stood “transfixed by the plot” of Balthus’s The Street (1933); then he stumbled on a Magritte in a Harper’s Bazaar in 1960: “There was this naked girl holding a mirror, with her whole body reflected in it. I thought it was a photograph, and wondered how an image like that was possible. But in fact it was an illustration.” In 1964, taking his inspiration from Atget¬—the only photographer he may ever have copied a little—Michals came up with his first series, Empty New York: in what are pretty much classical interiors, he imagines his adoptive city devoid of human presence. “Atget’s important for me,” he says. “I’ve always been fascinated by his highly theatrical images, his mises en scène, his mysterious atmospheres. It was him got me started on sequences.” Michals was then thirty-two and Cartier-Bresson, who had just finished his Mexican Notebooks, was already the founding father of the “decisive moment”. Like someone standing up to his teacher, photography’s troublemaker was incubating something that was going to revolutionize the approach to the image.

By adapting the complex mises en scène of Surrealist painting to photography, Michals would rebel against the “rule of logic” castigated by André Breton in his Manifesto of Surrealism. In The Woman Is Frightened by the Door (1966) and more notably A Man Going to Heaven (1967) and The Spirit Leaves the Body (1968), it is no longer a matter of true stories in a single shot, but of several juxtaposed images, a cinema-style revelation of an imaginary scene. The only photographers to have used the sequencing process before him were Eadweard Muybridge in his Man Climbing Stairs (1884) and maybe Chris Marker in his “photo novel” La Jetée (1962)—a film which, strangely, Michals has never seen. More than just a technical innovator, Michals came up with an in-depth way of handling all the issues seething inside him. What happens after death? What is memory? What is time? How to depict the human condition? Nothing is left to chance in his existential “comic strips”: these are stagings of ideas, concrete manifestations of his desires and his fears. Everything, for him, is photographic subject matter, especially those things that cannot usually be mentioned: anxiety, grief, dreams, nightmares, sexual attraction, memories. Unlike most photographers of our time—and even more, perhaps, of his own—Michals has decided to speak about himself, not others: “For a lot of people photography is mainly about description. I’ve always thought images have to be given perspicacity. Looking isn’t enough; you have to make yourself imagine.”

One of his most astonishing sequences is doubtless The Spirit Leaves the Body. In a darkened room a naked male body lies on a cloth-covered table. Using a succession of double exposures, Michals shows the man’s specter as it sits up, then stands. As if in a science fiction movie, this translucent silhouette walks into the foreground and moves past the camera. This is Michal’s genius at work: for the first time a photographer has succeeded in catching the human soul. In A Man Going to Heaven he returns to the theme of death, this time with a naked man climbing a steep staircase to the gates of Paradise. “The door,” he says, “is actually the one giving onto the roof of this building. Yeah, just up there; you should go take a look. Like that man walking towards the light, returning to the source, leaving his personality and the drama of his life behind him.” In Grandpa Goes to Heaven (1989), gravitas makes way for beatitude. Five images show an old man with angel’s wings ascending to heaven through a window as he smilingly waves goodbye to his grandson. Here death becomes so agreeable we almost want to experience the moment ourselves. So what’s the best way to die? “As you’re going to sleep,” Michals replies. “Imagine that at that moment you’re beginning to dream and you don’t even realize you’re dying. Your dreams bear you away towards new experiences—and life goes on.”

In Paradise Regained (1968) a motionless Adam and Eve are gradually undressed and their modern accessories—furniture, coffee cup, alarm clock—replaced by a mass of indoor plants. Here the artist is undressing not people, but society, wondering about a possible return to innocence, as if the state of grace really hinges on the loss of material goods. The Human Condition (1969) also makes play with change: a man on a platform in the New York subway is caught up without warning in a whorl of light which gradually transforms him into a galaxy at the center of the universe. “I’ve always liked thinking about the nature of my existence and finding inspiration in ideas like that. As Giorgio De Chirico said, ‘What else can one contemplate except the enigma?’”

Although the subject matter of these series seems complex, Michals’ photographs are actually fairly simple, each being an episode in his thought process. Mystical, sometimes supernatural, and firmly rooted in the metaphysical, they never lack an unmistakable feature of their creator’s personality: humor. Every photo is shot through with gags and eccentricities, just like the everyday existence of someone in love with pranks, absurd jokes and playful posing. For a good visual laugh, don’t miss Nightmare (1974), a series showing a horse playing hide and seek with a man playing solitaire; or Burlesque (1979), with the artist bestriding a giant brush and a friend doing the same with an enormous shoe. With every new photo, what’s more, he feels himself starting from scratch artistically: “A beginner brings all his attention to bear. It’s that much better when you don’t know what you’re going to come up with.”

This is what makes Duane Michals seem so far removed from today’s serious, celebrated contemporary photographers. He’s a softhearted poet, he’s authentic, and he’s not interested in conceptualizing for the sake of making a sale. Just the way he does things is enough to dismantle our idea of the image in a few minutes, then help us reshape it. He suggests possibilities and he puts the real questions, but without ever providing definitive answers: the questions are there to justify his love affair with the fantastic. Dreaming, for him, is the “mind’s midnight movie”, as in What Are Dreams? (1994), the portrait of a man dozing beside a snow globe with a mini-New York inside it. The nightmare, by contrast, is The Bogeyman (1973), a little girl sitting reading when suddenly a dark raincoat and a hat on a stand come to life. One thing for sure, when it comes to dealing with his obsessions—death being maybe the only one that hasn’t visibly gone away—Dr. Duanus is no psychiatrist: “A few years ago I wanted to prepare for my own death, so I started meditating on the subject. But that didn’t work, because I felt like an imposter. That’s the way things are. Nature is semantic and death is just a retreat from life.”

A taste for dissidence

Something Michals clearly learned early in life was the value of interchange: the way, for example, a simple meeting can irrevocably change the course of a life. This is the idea underlying the sequence Chance Meeting (1970), as breakdown of the encounter between two men who exchange glances as they cross paths in the street. Triggered by a personal experience on Times Square, this was the beginning of a consideration of the consequences of fortuitous meetings: between men and women or, as implied here, between one man and another. Intense visual contact giving rise to emotion. While some of Michals’ images offer tender visions of desirable bodies—How Nice to Watch You Take a Bath (1986) or The Most Beautiful Part of a Woman’s Body (1986)—his sketches do not exclude the violence we find in I Remember the Argument (1970), The Old Man Kills the Minotaur (1976), and most of all The Moments Before the Tragedy (1969) and its run-up to a woman being mugged by a man outside a subway exit. Like a war photographer he has a brutal knack of striking at the unconscious, of jolting us into awareness of moral and social decay. This brutality, though, is protected from vulgarity or sensationalism by Michals’ mastery of an all but forgotten aspect of photography of reality: the power of suggestion.

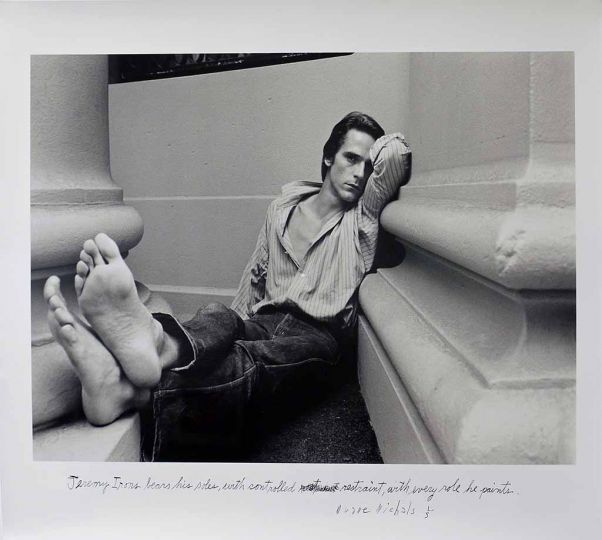

Michals also found photographic fame through another encounter—this time between image and text. By the 1970s his sequences, now of ten images or more, were leaving him dissatisfied. Also driven by a passion for words, he began writing titles above his images and poems below them and, gradually, on the images themselves: in By, Buy, Bye and To, Two, Too (1984) three characters call out messages to each other, painted in by the photographer. InThe Home I Once Called Home (2003) the words accompany a family album made just after his mother’s death, a stunning exercise in time travel that unveils the private lives of his family and secret happenings inside his childhood home. The viewer no longer has any excuse for not coming closer, looking and reflecting, and cutting free of the idea that photography is mere aesthetics. The poem at the bottom of In the Circle of All Things (1991) is written with a pen in an almost childlike hand, complete with a crossing-out, “Imagine this then if you can, Before time became a thought, When everything was not, And the conjurer had yet to play his hand. In this repose, centered, still, A clearness chose itself to will, Then with a kaleidoscope’s quick turn, All became from star to worm. And you who read, and I who write, Are conscious seeds of his delight.”

We can’t know for sure, but Michals’ talent must have bothered quite a few people. Beginning with Cartier-Bresson, met at a MoMA vernissage “around 1970”, whose polite hello morphed into “a hard stare” when he heard his name. Hardly surprising: Michals has always been at war with the immobile, perfect image, all that flawless definition and exclusion of the slightest blemish. Blur, in his oeuvre, is an art: at a time when it was simply the mark of a failed photo, he was using it to distort, to signal appearance and disappearance, to personify the invisible and trigger dreams. In some cases it was also a way of illustrating character, as in the three-picture 1958 series showing the features of Andy Warhol—another scion of McKeesport—gradually fading into nothingness: “When he got famous, I never heard from him again. This portrait is true to his image: Andy was a guy with no personality, someone almost fake.”

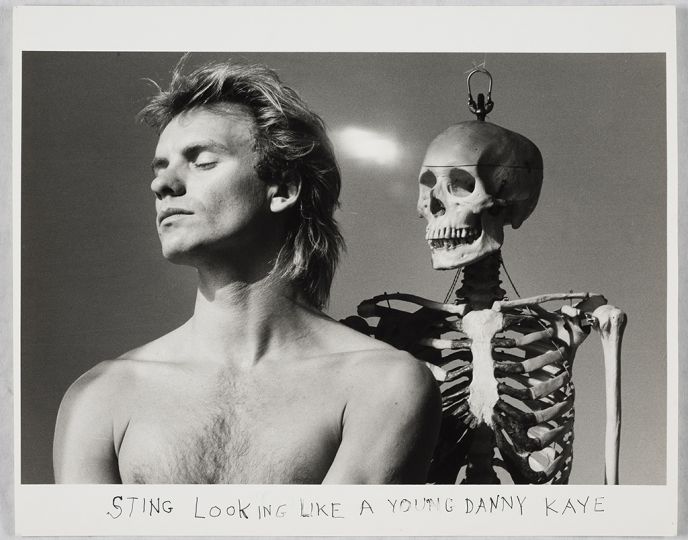

Naturally enough, there are people Michals can’t bear. For instance, those products of the market he satirized in Foto Follies: How Photography Lost its Virginity on the Way to the Bank (2006): pastiches of Cindy Sherman, Andreas Gursky, Wolfgang Tillmans, and Rineke Dijkstra, whose portraits he considers “frightful, inhuman”, nothing but “stand and stare” pictures. “A good portrait has to suggest something about the subject. It should have something to say about the personality of the subject or the kind of work he does.” There are others he thinks could have done better, like Robert Mapplethorpe and the pictures of homosexuals Michals sees as clichéd “because he photographed them without really knowing what he was talking about.” There are, too, those he respects: Irving Penn, who has a photo in a place of honor in his basement; and Francesca Woodman, influenced by Michals and admired by him for her authenticity. And then there are the others, the “unreal ones” he was bent on knowing before he photographed them. René Magritte, of course—Michals flew to Brussels and they had fun with double exposures and reflections in mirrors, and in a rare shot he immortalized the master sleeping: “Going to sleep fascinates me. Seeing someone go to sleep sets me imagining his dreams. When I photographed Magritte sleeping I wondered what fantastic dreams this man might be having.” And there was Marcel Duchamp, who lived on the same courtyard as him on 9th Street in Manhattan. A telling portrait of the artist seen through a window: “By chance I looked out my window and realized I was looking at his. I got a glimpse of him from time to time. For an admirer like me it was an incredible coincidence. And this is one of my favorite portraits.”

Sincerity and naturalness are Duane Michals’ watchwords, which is why he has no studio. He prefers natural light filtered through glass as the source of a graceful, inimitable melody that brushes over faces and objects with no trace of aggressiveness: “Every good photograph has atmosphere. Poetry is a matter of atmosphere.” His immediate surroundings are self-contained, providing him with the peace he needs in the visual/aural jungle that is Manhattan. If he needs fresh air or he’s feeling curious, he can retreat to his indoor terrace, from which he can still spy on the neighbors and wait for the next Duchamp to show himself. His photographs are chamber images, the bedchamber being the place where he rummages through his thoughts and turns them into bric-a-brackeries for the eye. Images that invite us to enter his private world, to submit to the spell of his finely honed sensibility. In 1978, in a Le Monde article headed “The Necessity of Contact”, writer/photographer Hervé Guibert quoted his finest message: “We must touch each other to stay human. Touch is the only thing that can save us. Usually the most important sentences have only two words or less: I want, I love, excuse me, touch me, I need, thank you.” Duane Michals is like that: he states the essentials about society, about people and the way they’re evolving, and about art too, however utopian he might seem. When he’s not at home he’s out giving lectures accompanied by his imaginary student, a plaster head he quizzes if his audience—and this really makes them crack up—doesn’t have any interesting questions. His urge to share and his bigheartedness know no limits, and maybe this is what makes him an artist apart. Let’s not be afraid to say it: his body of work is an opera for mankind. “When are you coming back?” he asks. “I like you, you know.” Me too, Duane.

Jonas Cuénin

Duane Michals, The Narrative Photograph

Through December 3, 2016

Jackson Fine Art

3115 East Shadowlawn Avenue

Atlanta, GA 30305

USA