Don McCullin was the president of the jury for the 30th edition of the Prix Bayeux Calvados-Normandie.

Michael Naulin from Le Figaro did a fantastic interview! There it is :

Don McCullin: “Photojournalism has been poisoned by the art world.”

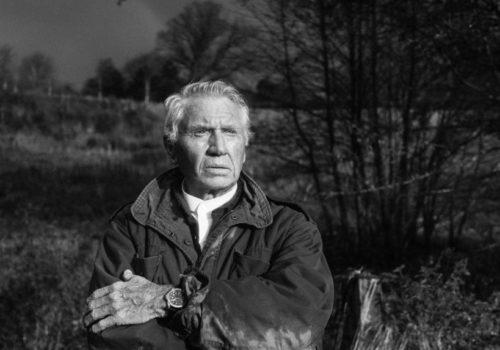

President of the jury for the 30th edition of the Bayeux Calvados-Normandie Prize, the great British photographer exhibits the famous photos of the conflicts he covered. He is 88 years old, and takes a lucid look at his career.

Don McCullin dedicated his life to photography. Not just that of wars, that of landscapes too, of ancient ruins, of social crises. The great witness of human tragedies, defender of an intense black and white that hits you like a punch, is exhibiting his iconic photos of the great torments of the world in Bayeux. This weekend he also chaired the jury for the 30th Bayeux Calvados-Normandie war correspondents prize, which rewarded, in the photo category, the Italian-British Siegfried Modola for his work on the Burmese rebellion. A veteran of the image, a relentless craftsman, with a proud “so British” look intact, the lion with blue eyes and a humor tinged with melancholy puts away his tools little by little, and tries to make peace with his inner shadows.

Le Figaro. – One of the exhibitions in Bayeux pays tribute to the photographers and journalists who covered the Allied landings of June 6th, 1944. You are yourself a child of this war…

Don McCullin. – I would have liked to be one of these correspondents. But I was not yet 5 years old when the war broke out (he was born on October 9, 1935, Editor’s note). I lived in London, which was relentlessly bombed by the Germans during the Blitz. It was terrifying. I was sent to the countryside and then to the north of England where I experienced very difficult times. My father died when I was 13, I became determined to do something with my life. I succeeded, but at the cost of the horrors of the wars I covered and the victims I saw die before my eyes.

You were a great witness to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. What is your reaction when you see the current situation in Israel and the Gaza Strip?

I have followed this story for half my life. In my humble opinion, I think that if the Israeli government had created more of an atmosphere of peace through dialogue, we might not be here today. On the other hand, the Palestinians, to whom I am very attached, have never had good leaders, they have been governed by incompetents and thugs. The people of Israel and Gaza should be able to live their lives peacefully. No one should suffer the consequences of bad government and arms trade. No one.

Do you still have the inner flame that pushes you to go there?

Obviously. Every time I see a conflict like this or the one in Ukraine, I want to go and cover it. I have it in my blood. But my body is telling me, “It’s over for you Mr. McCullin, over.” »

Among your photos exhibited in Bayeux is a landscape shot, that of the Somme. Your friend, the British novelist John Le Carré, said of you: “Wherever he goes, he turns it into a battlefield”…

There is an element of truth in that, especially because I photograph my landscapes mainly in winter, when the trees no longer have leaves. They look like skeletons then. I also make the sky very dark. I call it the “Wagnerian sky”. Wagner often sounds in my darkroom. I also love Bach and his music that takes you down at the same speed as your heartbeat. It soothes me as much as the landscapes. There is no better therapy.

Is your darkroom also a refuge?

It’s like being in your mother’s womb. This reminds me of the photo of the fetus taken by the photographer Lennart Nilsson. The red light in the womb is the same as that in the dark room. There is something symbolic. In my youth, I spent entire days holed up in this room. Now I can’t go there for more than two hours a day simply because my legs no longer support me. I’m thinking of closing the door this year. Having spent more than sixty years of my life there, it’s as if I had smoked three packs of cigarettes a day. Chemistry is extremely toxic. But by processing my own photos, I took control of their power. I wanted them to be dark and intense, so that you couldn’t walk past them without looking at them.

After being confronted with the madness of war, how do you avoid sinking yourself?

The line with madness is very thin. I could have gone crazy going to war. I don’t suffer from post-traumatic stress because I grew up in a violent, very poor, uneducated environment (Finsbury Park, a working-class neighborhood in north London, Editor’s note). If I had gone to college, my mind might have collapsed. I left school at the age of 15, barely knowing how to read. I quickly felt that life was against me and that I had to overcome it. So I charged like a bull into the arena. But looking back, I now view my life as incredibly selfish, because I only thought about myself and photography. My family was terrified that I wouldn’t come back.

You were knighted in 2017, is this a revenge for this difficult childhood?

I obviously think of the conditions in which my parents and I lived, we all slept in the same room, without toilets or bathrooms. One of the things to know about England is that we still have a class system. Everyone thinks that has changed. This is not the case. So I have no illusions about the acceptance of my title, I know where I come from. I did it for my children whom I abandoned while chasing this crazy life as a photojournalist.

Did photography save you?

I didn’t set out to become a photographer. I sincerely believe that it was photography that found me. The journalists with whom I traveled the world became my guardians. I listened to them. I also traveled with renowned writers like John Le Carré. They became my schoolmasters. I have always been an apprentice in photography, even today. I loved it because it is magical. But I’m about to give it up, I’m too old. All I want is to stay in my home in Somerset (a county in the southwest of England, editor’s note), and not be persecuted by myself because I am my own biggest persecutor.

How do you view the profession today?

Photojournalism has been poisoned by the art world. What is shown here in Bayeux is not art. We talk about photojournalism, war and tragedy. Many photographers have lost their lives while exercising their profession. Is it worth getting killed for a photo? The answer is obviously no. But why are we going there? What is pushing us to leave? Being caught up in the life of a photojournalist has the effect of a drug, it is difficult to escape.

Interview by Michael Naulin for Le Figaro

© Michaël Naulin / LeFigaro.fr / 16.10.2023

Bayeux Calvados-Normandy War Correspondents Award, exhibitions until November 12, 2023.

Read: Don McCullin. Le monde dans le viseur, d’Alain Frachon, Michel Guerrin et Jon Swain, Équateurs, 128 pages, 23 euros.