His name is Diego Goldberg.

He is Argentinian. He is one of the most formidable photojournalists and photographers of his generation.

He is one of the very few to have been accepted in the intimacy of François Mitterrand. He also has this implacable look on photography today.

This edition is dedicated to him.

Jean-Jacques Naudet

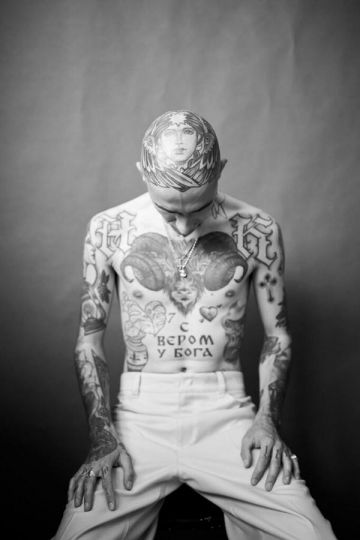

Diego Goldberg by Eliane Laffont

I have known Diego for more than 30 years. Since his beginnings as a correspondent in Latin America for the french photo agency Sygma, then as a Sygma staff photographer in Paris and later, while I was Director of Sygma in the US, working with me in New York.

There are several facets of his work and personality that I would like to highlight:

a. As a photographer, I have always admired his keen sense of composition – strict, perfectly balanced, always a means to deliver a particular point of view – and the development of a personal and recognizable style, something rather unusual.

b. As a photojounalist, he has always had a deep comprehension of the issues he had to cover, wherever in the world that might be. He was always interested by the “theater of politics” and in the many stories he covered in different countries he tried to develop precisely this angle. What is probably his best known work, the campaign and later presidency of Francois Mitterrand, is a clear example of this: he gained special access to the character and from this privileged vantage point developed a lasting portrait of one of the important political figures of the last century.

c. His multiple interests have taken him to other related activities in our field. Education, in many workshops and specially at the World Press Photo Masterclasses; as a respected jury member of the most important photo contests, most recently as Chairman of the Jury at the World Press Photo Contest and also as a picture editor, during his 6 year work at Clarin, the argentine newspaper, when he was the Director of Photography.

All these activities and experiences have made Diego a quite unique personality in the international photo community. After Clarin he has restarted his career working on long term projects, taking some distance from the urgencies and constraints of the press. His last project, “Chasing the Dream”, undertaken for the United Nations is a good example of this new direction. Complex, beautifully photographed, comprehensive in its scope, it also shows his commitment to use photography as tool to communicate and understand the issues of the day.

Eliane Laffont

Diego Goldberg – 1970’s

A while ago, for the first time in almost 45 years as a photojournalist, I finally was able to look at everything that I had done and lived, when all of my work, which was stored in France, was returned to me. Some pictures where also the incontrovertible proof that our memory plays tricks on us: on many occasions things did not happen the way I remembered them. Revisiting the work I found many valuable images that were never edited or used: it was an exhilarating experience to be able to do my own edit of the most interesting work I had done.

At the same time it forced me to rethink what has happened to our profession in all this period of tectonic changes with the demise of most of the iconic photo agencies of the past, internet, digitalisation and one camera in every pocket: the “end of the world “ as we knew it.

The first thing that has to be mentioned is that those photo agencies ( Sygma, Gamma, SIPA, Black Star, Contact, etc.), were a US / European business. American and European photographers feeding mainly the western press. A select – and talented – group of men and women that roamed the world, disembarking for a few days on foreign lands like anthropologists on Mars. And then to the next stop. The “Day in the Life” book projects in different countries got most of us together for a few days which proves how few we were.

Foreign lands means foreign cultures and it would have been impossible to understand and therefore depict or document the different and rich realities that local photographers knew better than anybody, specially in the few days that assignments provided.

This is not a critique : I am just stating facts and trying to shed light on a very important moment in the development of photojournalism that was so influential worldwide. But the reality is that it was a US / EU phenomenon that provided stories for the western media.

I come from a third world country and that made me aware that the rest of the world lived on a parallel universe: a diverse and very rich one. There were thousands of newspapers and magazines and thousands of photographers either on staff or freelancing worldwide. And therefore photojournalism was more, much more than the privileged few and their sometimes extraordinary work.

It is undeniably true that not all of the work these “unknown” photographers produced was of high quality: much of what was expected from them from the different newsrooms was just a visual confirmation that what the text described really existed. As I’ve often said they were the public notary of the covered events, an illustration that was necessary for a most appealing layout. Very seldom did they provide a complementary and personal point of view to the story to enrich its content.

In 1996 in the midst of a personal (photographic) crisis I accepted the job of Director of Photography at Clarin, an Argentinian newspaper which at the time had the largest circulation in all spanish speaking countries. After six years working with more than 50 photographers (staff and stringers) it became clear to me that something is seldom discussed when addressing the problems photojournalism is facing today, and that is the role of the picture editor

The printed press is in turmoil with diminishing returns, lower readership, the transition to the web, etc. The other side of the coin is that in the digital world there is more space with negligible extra cost for the intelligent use of photography. And here comes the weakest link in the chain: creative, audacious, risk taking picture editors who can advance the use of work that many photographers are able to produce, now more than ever.

It is a profound mistake to believe that picture editors’ only task is to choose pictures. They are the gatekeepers and it is their responsibility to promote, elevate, assign and use good photography. Not all is bleak, there are many examples worth following and I will only mention one: The New York Times. They have embraced the web wholeheartedly and use the myriad possibilities that the digital world offers and use photography creatively, developing a language that enriches the journalistic task at hand. And in this, obviously, the work of their picture editors is essential.

A camera in every pocket. This is a new and extraordinary reality: never have so many people produced so many pictures. I’ve been often asked if this is a danger for the future of photojournalism. Everybody can take a picture with the modern tools available but that doesn’t mean that they can interpret the world, develop a personal point of view or master the language. In this sense I always mention the example of the advent of literacy. Everybody can read and write, very few are writers or journalists.

Every day countless number of pictures are used in all sorts of publications world wide. The burden of using our expertise, talent and knowledge to tell the stories that we deem relevant for the community falls on us, photographers and picture editors. It is a fight worth fighting.

The 1970s was the decade of learning. I came from an unrelated background to photojournalism: studies, first in physics and then architecture. Photography was just a hobby, which I practised in my spare time. What was growing during that period (60s) was my interest in the world at large, the urge to witness, see by myself and tell those stories.

And then and epiphany. On the last year of my architecture studies I suddenly realised that I had limited talent to pursue that profession. Living in Argentina my contact with the world was through magazines and the work of photographers that I admired. Soon, that was the dream that I began to chase.

I never worked in the local press, which was quite lively at the time, with many newspapers and magazines, but my hopes lied elsewhere. I went directly to foreign correspondents and got one day assignments from time to time. I established a contact with Camera Press, the British photo agency, and started travelling and covering events in different countries in Latin America.

Then in 1974 the newly formed Sygma Agency, having seen some of my work in european magazines, gave me the possibility to work with them as their correspondent in the Latin American countries. And so began this long journey….

In 1976, an enormous frustration: most of the countries in South America had military dictatorships and what was happening was not visible: thousands disappeared, killed or tortured. A tremendous reality that I was unable to document as a photographer. These thoughts reached Hubert Henrotte, head of Sygma, and he offered me to join the staff of photographers in Paris.

And so began a new chapter: changing countries, forming a family (see The Arrow of Time) and accumulating experiences.

Diego Goldberg