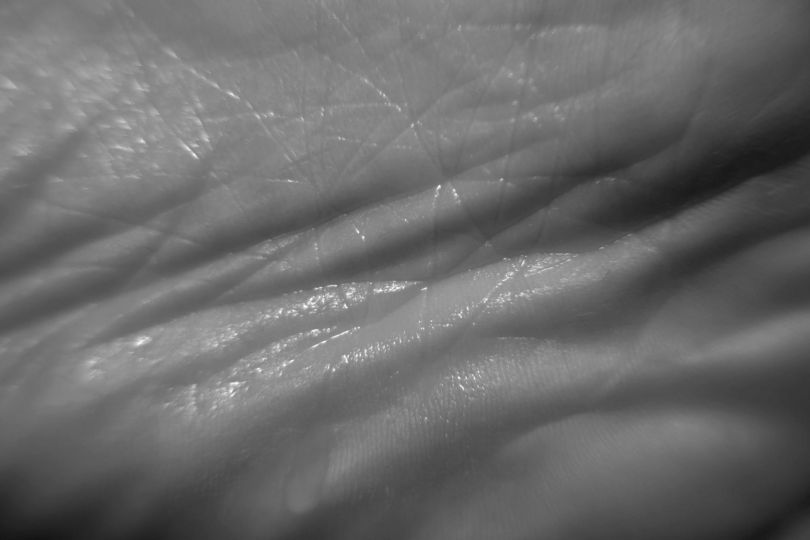

Contrarily to the majority of encyclopedic approaches initiated in the second half of the 19th century, constructed on the principle of the collection and classification of different preexisting data, images collected according to aesthetic or thematic criteria, the Archives of the Planet first came into existence as a production company, which operated from 1909 to 1931. As affirmed by its founder Albert Kahn, banker, philanthropist, and pacifist, direct fieldwork for photographers and filmmakers is a central element: “Field study seems to me to be the only way to make true geography. They will be most valuable and produce their fullest effect when our little planet has become too familiar to you.”

Behind a homogeny of support (more than a hundred hours of film and close to 72,000 autochromes), the Archives of the Planet presents a real heterogeneousness, crossing different disciplines, influences, outside connections, types of stories… This project, in the heart of a complex time, became a bridge between two centuries through multiple references. It lays testimony to a world that was deeply changing, that expanded at the same time it contracted, making spaces interdependent. A cosmopolitan banker who took chances on South African diamond mines and negotiated with the financiers of the Meiji empire, a tireless traveller who believed that experiencing other places was necessary to the education of young graduates, a militant pacifist who was there when great European powers redrew the boundaries of the world, Albert Kahn was, in many respects, a player in this active globalization.

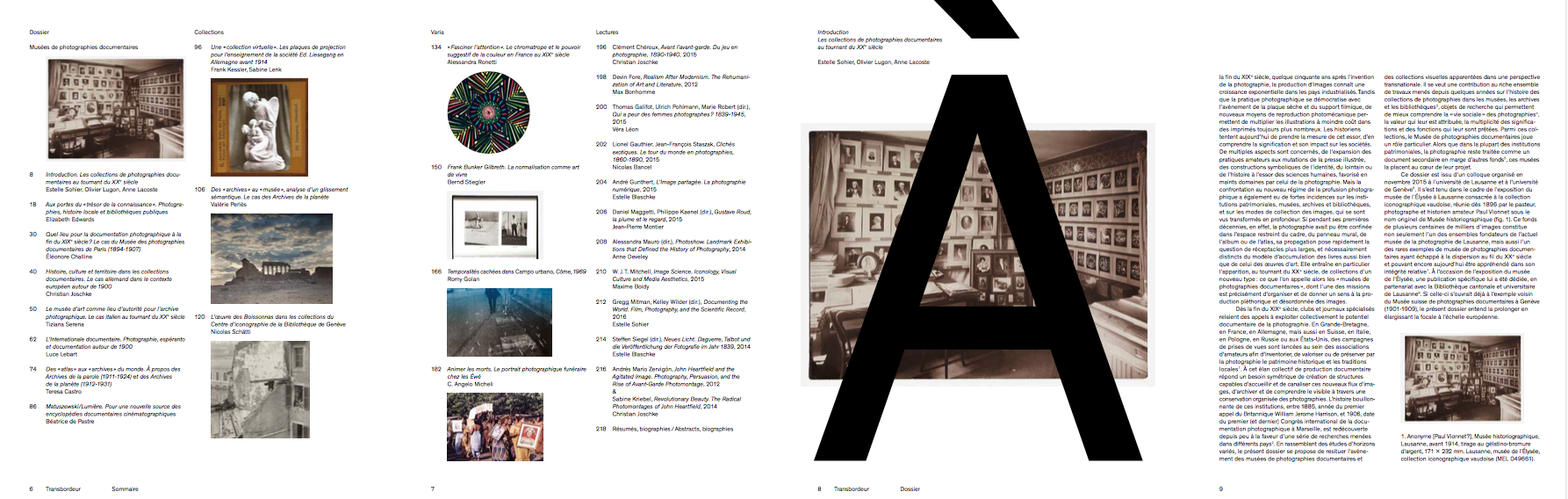

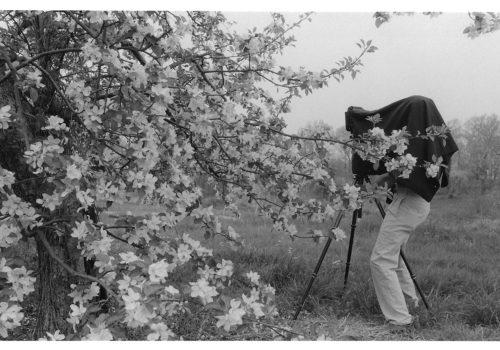

With Kahn, traveling experience was central. In 1909, he went on a world tour . He was accompanied by his mechanic-chauffeur, Albert Dutertre, equipped with a stereoscopic camera, a film camera, and a phonograph recorder. The project was modeled from the desire to accumulate as many possible facets of reality, a sort of total archive. Even though Dutertre made a few autochromes, Kahn was really the one to discover the potential of this process during the projections organized by Jules Gervais-Courtellemont. A travel photographer, he had, since 1908, given his “visions of the Orient”, conferences supported by color images brought back from his travels. The impact of these projections on the banker marked the true starting point of the project, dictating his implementation and his valuing system. The photographs made by Gervais-Courtellemont did not reveal any topography, but resulted in scenes that leaned towards an orientalist genre. Some of them sprouted the documentary collection (the first inventory issues were attributed to images acquired from Gervais-Courtellemont), confirming the ambiguity of the “scientific” positioning postulated in the beginning. The recordings of the explorer-lecturer had also long-served as a reference for the operators of the Archives of the Planet.

The collection of images taken by the camera operators, which were autochrome or film, were designed to be projected. The projections established an essential element of a refined device finalized in the banker’s home in Boulogne. Albert Kahn maintained a dense social network there, composed of representatives of political, religious, artistic, intellectual, and scientific spheres, coming from all over the world. These guests on the banks of the Seine, all day long, revealed, above all, a business of seduction: lunch, strolls in the garden, intellectual exchanges without any formalism. The garden, composed of different landscapes (French, English, Japanese, but also a marsh and Vosge forest) seemed like an initiatory location within which essences, flowers, rules of composition, ambiences of diverse origins cohabited to create a harmonious landscape.

The meandering was interspersed with film and autochrome projections which, in the filiation of those organized by Gervais-Courtellemont, functioned most of the time as an invitation to travel (color and light effects, remarkable architectural elements, works of art and archeology, picturesque scenes…) The spectacular dimension inherent in this way of viewing is not to be neglected. Pierre Deffontaines, geographer student of Brunhes, described the courses of his mentor, insisting upon the effect produced by autochrome projections on the audience: “They [the ideas] do not stay isolated of theoretical, they are supported by examples, or rather by visions, because these are visions of color photographs, so beautiful that they are occasionally applauded.” The word “vision” is an explicit reflection of the semantic register used by Gervais-Courtellemont. Seducing, touching, moving… in order to educate.

By the demonstration of the possible coexistence of cultural diversities, the spectacle of rich heritages and natural phenomenons, Kahn touched the hearts and souls of the guests. This sensitive dimension, sharpened by an immersive process of several hours in the Boulonnais site, imparted an formidable efficiency onto Kahn’s pacifist message. The collections of gardens and images mutually matched and illuminated each other, demonstrating a desire to render reality through different methods. The poetic combination of the garden responded to the supposed objectiveness of the recorded images. Beyond the temptation of embracing reality in its global nature, in the end, it was the principle of abolition from a distance that arose. Kahn, from then on, rendered the world accessible, within sight during projections, within reach during strolls in the sumptuous garden.

Valérie Perlès

Valérie Perlès is the director of the Musée Albert Kahn in Boulogne-Billancourt, France. This text appeared in the first issue of the magazine Transbordeur.

Transbordeur – Photographie, histoire, société

Issue 1 – Dossier « Musées de photographies documentaires »

Directed by Estelle Sohier, Olivier Lugon and Anne Lacoste

Published by Editions Macula

236 pages

29.00 €