David Goldblatt died yesterday in Johannesburg. He was 88 years old. We devoted a long subject to him during the opening of his retrospective in Beaubourg last February. Here it is again.

Speaking of writing, Jorge Luis Borges advised that one should seek a “secret and modest complexity.” David Goldblatt has expressed his affinity for this formula; indeed, it could be the key to his whole oeuvre, as the photographer brings to light a situation that allows us to examine the world in all its nuances and countless intricate possibilities.

We can retrace David Goldblatt’s career path starting with his early works shown at the Centre Pompidou in a section of the exhibition devoted to history. Thus in 1966, he became fascinated with the gold mine located just outside Randfontein, the town of his birth. Not only does the photographer capture the miners’ faces in his evanescent pictures whose coarse-grained texture lends the images a ghostly appearance, he also takes us behind the scenes: the general manager’s bathroom, the overseer’s “boss boy” in charge of personal security, the general view of the mine and the machinery. Goldblatt takes in everything: he is an impartial witness who adapts to his subject and excels in all the possible ways of taking a photograph. “I don’t consider myself as an artist,” he says. “I prefer to think, not that I am working in art, but rather than I seek the art of doing my work well.”

Johannesburg

“I grew up very privileged. At home, I had Paris Match and looked at the stories of photographers who inspired me and made me want to take up this profession.” This encounter helped Goldblatt develop his talent as a documentary photographer capable of conveying the individual voice of each story through images. This ability is evident in his series devoted to Afrikaners, that is, white South Africans of German, Dutch, French, or Scandinavian origin who actively supported segregation during the apartheid. David Goldblatt does not stop at painting a bleak, true-to-life picture, but points out the extent of inner divisions within the group.

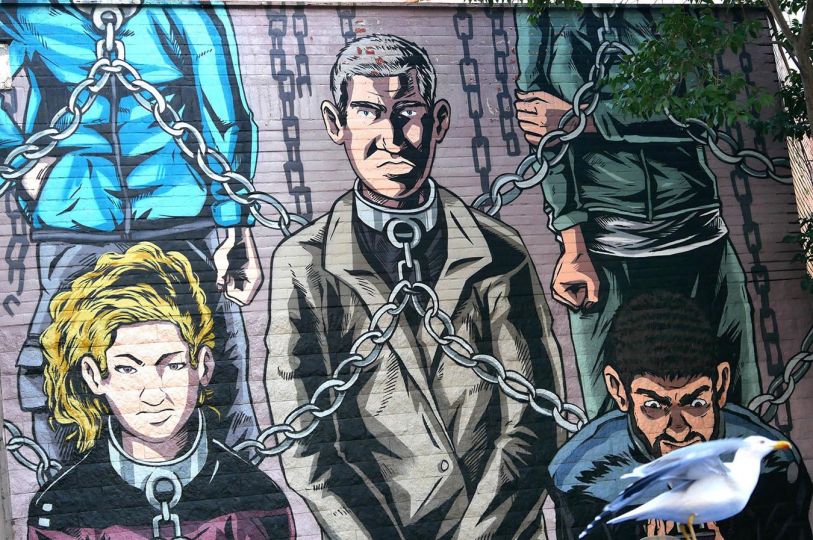

All of the photographer’s work revolves more generally around the larger issue of social division. Black domestic workers interact with their white employers, and Afrikaners may be less racist than one might think. In Goldblatt’s work, there are no shortcuts or stereotypes; on the contrary, every photograph is the fruit of careful reflection about the faces and landscapes he comes across. It is an invitation to meet people, as in the case of the handsome portraits of Johannesburg inhabitants: the housewife beaming at the photographer, the singer lounging on the sofa in her apartment, or the stern-looking official glued to his desk. In the photographer’s viewfinder, a worker is placed on equal footing with the employer, a bum with a diva. Goldblatt systematically positions himself at an elegant distance that is distinctly his own.

Buses

His portraitist’s talent is coupled with keen awareness of the society around him. David Goldblatt followed, for example, the life of a farmer named Kas Maine, which aptly illustrates the problems faced by black peasants unable to own land under the apartheid. Forced to live on a small plot of land, the farmer shows his tiny makeshift shack, which the photographer makes a point of immortalizing. Similarly, in a series focused on bus routes traveled by the poorest—mainly black— population on their way to the remote locations where they work. Goldblatt recorded the hardship of this exhausting commute—up to eight hours a day!—and thus documented the underside of a segregated society fractured by a profound socioeconomic divide.

Structures

At the heart of the exhibition, David Goldblatt added recent photographs, which bear witness to the ongoing developments in his country, often in the direction of decreased discrimination. Nevertheless, as his images show, much work remains to be done in South Africa, where vestiges of the apartheid are very close to the surface. This is the message of the series titled Structures, in which the photographer reveals the remnants of the past and traces the lines of division that run through an extremely splintered and hierarchical society. In this series, Goldblatt focuses on architecture as much as he does on people. For example, he looks at empty residential buildings, which were part of an abandoned housing project designed exclusively for whites. Further down, the photographer shows a footbridge over a railroad, accompanied by the following caption: “Pedestrian bridge over the Cape Town–Johannesburg railway. … people … crossed this bridge in two streams—‘White’ and ‘Non-White’.” The signs are now gone, but the divided staircase continues to be used by a population of about 2000.

Reflection

In short videos set up around the exhibition, David Goldblatt poignantly narrates the stories of the places and the people he has photographed. He contextualizes every picture, thereby showing his commitment to his work. Nothing seems to escape him, and every image is the result of prolonged reflection which authorizes him to capture nothing less than a faithful image of a complex reality full of contradictions. While some photographs point to the shortcomings of this society, others reveal glimmers of hope, for example the picture of a man, shown from behind, pushing a wheelbarrow as he builds a house on his own land after decades of being denied access to housing. “Looking at his contracted muscles, we are led to believe that this man is very content,” comments David Goldblatt in one of the videos.

Jean-Baptiste Gauvin

Jean-Baptiste Gauvin is a journalist, writer, and stage director. He lives and works in Paris.