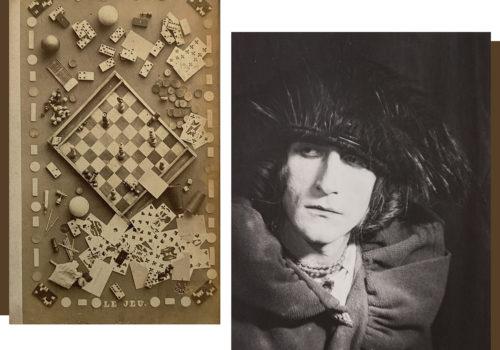

This is the 37th dialogue of the Collezione Ettore Molinario. We talk about Marcel Duchamp and his passion for chess, but above all we talk about the roles that play on the chessboard of life and art. A great “jeu”, this challenge, as suggested by the carte de visite of Allain De Torbéchet & Cie. A game I would never want to stop.

Ettore Molinario

What reality denies, fantasy eagerly makes its own. So let’s try to imagine a chess match between two of the most singular players in history, a woman and a man, a very elegant amazon in court battles and an equally elegant dandy who killed painting and invented different gestures to be an artist. At the sides of the chessboard, Marcel Duchamp, we know everything about him, and Beatrice d’Este, wife of Ludovico il Moro in 15th century Milan and a famous chess player, so much so that she changed its destiny. In fact, Beatrice is responsible for the advancement of the Queen to the most important piece on the chessboard, the only one to radiate her power on every square. After Beatrice, the King, the Shāh in Persian chess, is only a prey, a symbol to be protected, captured and killed in the Shāh māt, which we translate as “checkmate” but which literally means “the king has no escape”.