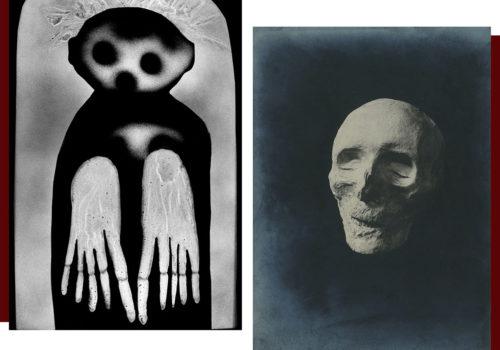

This is the 33rd dialogue of the Collezione Ettore Molinario. A dialogue that addresses the dark side of power, because nothing is more crazy, cursed and seductive than the thirst for command. We are invited to this reflection by Roger Ballen, an author whom I love very much because he cherishes the power of the unconscious and its ghosts, and an anonymous master who was bestowed the Shakespearean destiny of portraying the spectre of one of the most powerful men in Europe.

Ettore Molinario

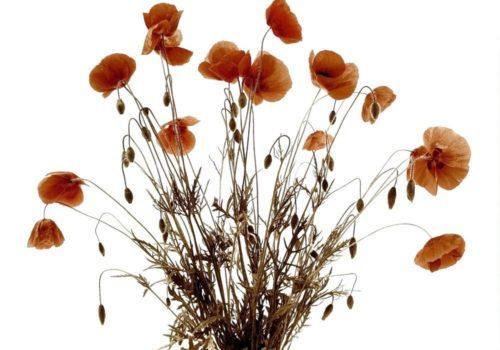

The apparition occurred on 5 December 1793 after one hundred and fifty years of deep sleep, when a handful of revolutionaries profaned the tomb of Cardinal Richelieu, built by the former prime minister in the heart of the Sorbonne, where he had been student and rector. A few months after the beginning of the Regime of Terror, the remains of the supreme enemy appeared, he who had strengthened the monarchy of Louis XIII and pushed it towards absolutism. Richelieu was « the powerful statesman who made France and Europe tremble with his policies » as we read in The Three Musketeers. Of his mortal remains the rebels kept only the skull and in an instant that head, which had imagined a military destiny for itself but had studied theology instead, the head that had led a king and his armies in one of the longest European wars, the head that had founded the French Academy, regulated the French language and institutionalised the theatre transforming it into an instrument of political consensus, well, that head became a ball between the feet of a group of children who, laughing and dribbling, rolled it around the streets of Paris.

So the legend goes and it is said that Abbot Boshamp, moved to pity, picked it up and kept it with him, entrusting it in his will to Nicolas Armez, mayor of Plourivo in Brittany. A village too small for such an honour, so much so that the prefect of the Côtes-du-Nord claimed the relic and only after contemplating it for a long time did he return it to the Sorbonne and its eternal home. It could have been the longed-awaited rest for a man like Richelieu who in life was the subject of infinite conspiracies and of many succeeded in beheading their perpetrators. But it was not the case because in 1894 Gabriel Hanotaux, the Cardinal’s biographer, asked to have the famous head exhumed again, at which point it was photographed and printed in hundreds of copies. And then yes, becoming a demonic souvenir of Paris, Armand-Jean du Plessis Duke of Richelieu conquered supreme power.

Just like the frightening ghost of Roger Ballen, inspired by the engravings left on the windows of a former women’s mental hospital and collected in the extraordinary volume The Theatre of Apparitions, so that sixteenth-century face by date of birth but universal by destiny continued to disturb dreams, revealing the madness of those who yearn for the absolute government of themselves, of others and of the world, and take no leave from that absoluteness, not even in death and are therefore forced to wander among the ghosts. This is what Richelieu’s face tells us, and a warning of this torture were the eye sockets empty like craters, the eyelids on which the eyelashes could still be counted and from which one might fear a glow from the afterlife would eventually emerge. Of course, should we not have just a post-mortem portrait of the Cardinal’s body and if photography was an invention of the 17th century, maybe we would also retain the image of a Richelieu intent on cuddling one of his beloved cats in the rooms of his princely residence, now the Palais-Royal, just a stone’s throw from the Louvre. He had fourteen of them, mostly Angoras, and we like to remember at least three names: Lucifer, Ludovic-le-Cruel, Ludoviska. In other words, photography does not devise destiny, it can only attest it.

Ettore Molinario

DISCOVER COLLECTION DIALOGUES

https://collezionemolinario.com/en/dialogues