This is the twenty-fourth dialogue from the Ettore Molinario Collection, which means two years of happy and stimulating encounters. To celebrate this anniversary I have chosen an ancient and contemporary theme, the myth of the knight. From East and West, a man traveling in and out of the bounds of freedom, who I think looks a lot like me.

Ettore Molinario

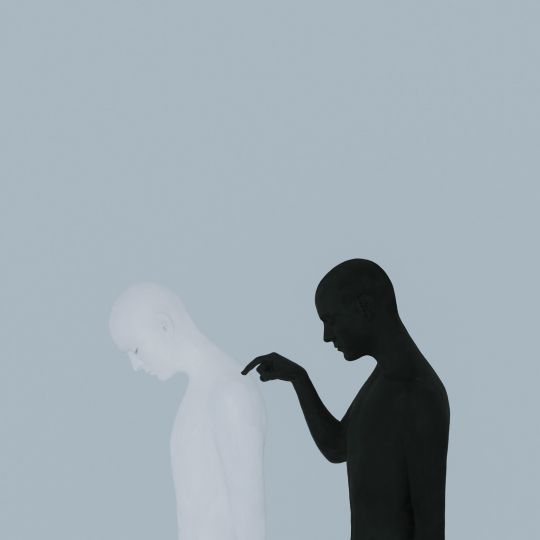

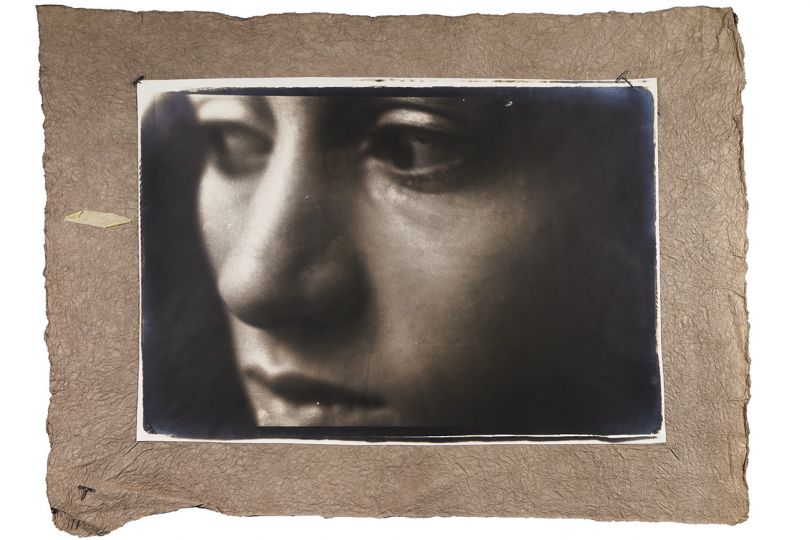

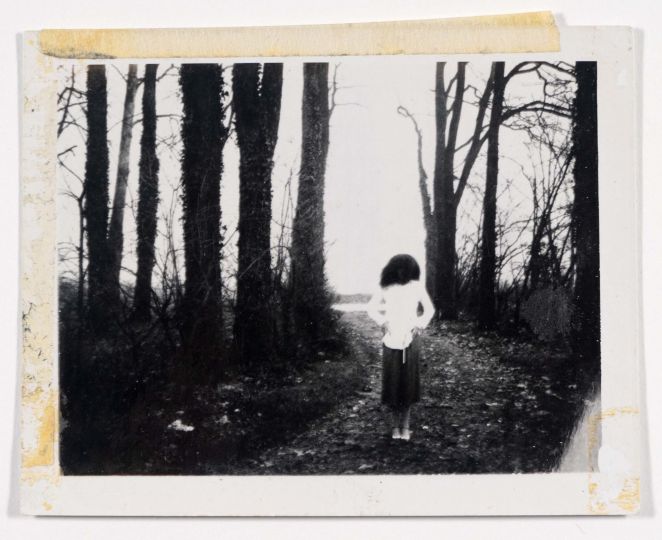

No samurai would ever want to be a ronin, a « wave man », a wanderer. A fault, that of freedom and the lack of a lord to whom to offer one’s services, which he had to atone for, if he was a man of courage, by performing harakiri. The young samurai, portrayed around the 1870s by Suzuki Shin’ichi I, was experiencing an equal drama, if not greater because the entire warrior class was dismissed, since the rulers of the Meiji era had preferred a regular European-inspired kind of army. As if centuries of Japanese history had been condemned to the ultimate sacrifice, when facing the lens those melancholy eyes knew that they would no longer contemplate the fury of battle, nor would they follow the sparkle of the katana, where the soul of the samurai resided, nor the gleam of the shorter blade, called wakizashi. The armour, the surplice, the helmet would remain helpless, lifeless objects, horrible souvenirs, and no one would compare the splendour of the cherry blossoms to the grandiose sight of a samurai wrapped in his armour. « Among the flowers the cherry tree, among the men the warrior » one would say to evoke the supreme beauty. But also its fragility, because as a gust of wind made the white petals fall, so the samurai died under an enemy sword blow. At the same time in Europe, on the latest waves of romanticism and the neo Gothic revival, the myth of the errant knight flourished in another way, in all its introspective richness, and the character of that lonely man, without borders, faithful to his independence, for this was the absolute value, became a symbol of the only possible life. Outside the social rules. Outside the gears of the economy. Outside a sentimental horizon already so bourgeois as to force the fate of men and women into the family. On horseback, even in the forests of the metropolis, modern knights fought other crusades and celebrated solitude, which was above all an unequal battle against senselessness, ineradicable violence, the evil in everyone’s existence.

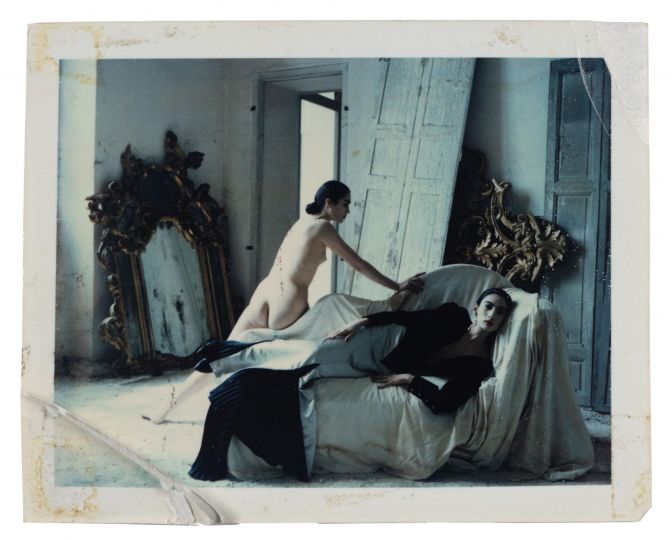

In the terrible years of the Second World War, this symbolic figure inspired Serge Lifar, dancer of the Ballets Russes, choreographer, maître de ballet of the Paris Opera, theorist, writer, in a word one of the greats who revolutionized the dance of the twentieth century.

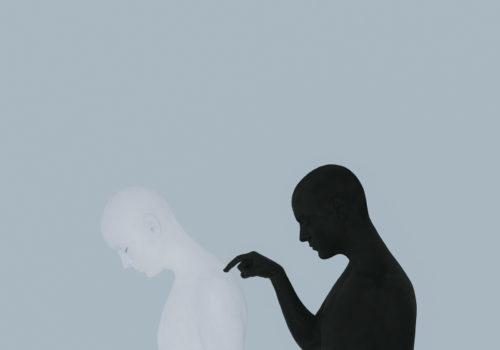

In 1941 Lifar creates the ballet Le Chevalier et la Demoiselle, and the lady, transformed by a sorcerer into a white doe, is a hypothesis of love, but above all it represents occupied Paris, and to the capital belong his theatre, his corps de ballet, his orchestra. A city within a city to defend, even at the cost of heavy compromises with the Nazi leaders. In the Harcourt Studio, founded in 1933 by Cosette Harcourt, Lifar wore the stage costume. The armour was embroidered on the legs and on the chest, and the spear, slightly oblique because even in static nature everything is in motion, brought back memories of the deeds of medieval tournaments. But perhaps the image of another war had returned to the dancer’s mind and of another knight errant, himself a boy, who in 1922 at the age of seventeen, alone, left Kiev invaded by the Bolsheviks, and fleeing by sleigh through the woods of Polonia reached Warsaw, and from there, in January 1923, arrived in Paris and joined the company of Sergej Diaghilev. « I was a free citizen of the universe in the freest capital in the world » Lifar recalled in his autobiography. It was a hundred years ago. What would the knight Lifar have done today in his city at war once more?

Ettore Molinario

www.collezionemolinario.com