Sarah Schorr is an American photographic artist, educator and researcher living in Denmark. Presently, she is completing her Munn/Versailles Foundation Fellowship Artist Residency at Claude Monet’s Garden and home in Giverny, France. She is a daily swimmer, which has drawn her to the subject and nature of water. Monet conceived and was inspired by his gardens which included water as a focus. As well, Schorr’s captivation comes from water and light––transparent, translucent, reflective, and opaque.

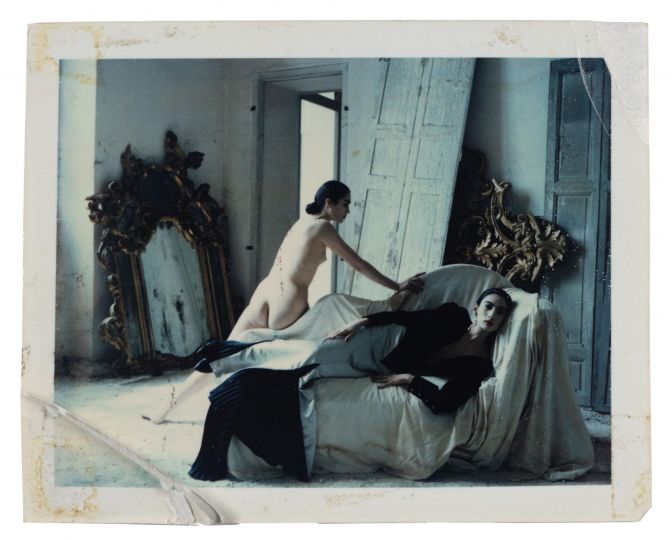

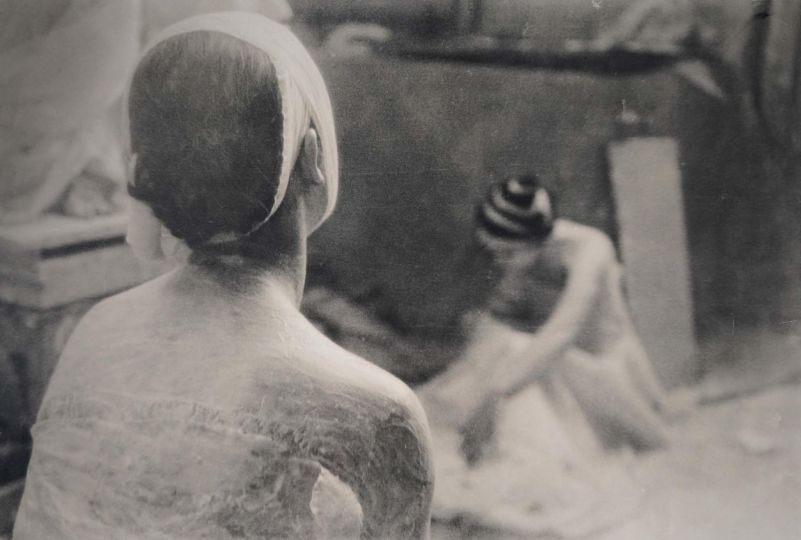

Schorr’s work has been widely exhibited since her first solo show at Yancey Richardson Gallery in New York. Recently, Schorr’s image ebbtide received the director’s prize at the Griffin Museum of Photography which will result in an exhibition and catalogue. In 2020, Schorr’s work was honoured by the Julia Margaret Cameron Award for women photographers in the category of nude (first prize) as part of an exhibition at the Fotonostrum Gallery in Barcelona, Spain. Sarah received her BA from Wesleyan University, her MFA in Photography, Video, and Related Media from the School of Visual Arts and her PhD in media studies at Aarhus University. Her book “The Color of Water,” with words by Elizabeth Avedon and Anne Marie Kragh Pahuus accompanied a (2021) solo show of her work at Galleri Image in Denmark and a (2022) solo show at the Northern Photographic Centre in Finland.

Sarah’s Website: https://www.sarahschorr.com

The Color of Water book & Prints: https://www.sarahschorr.com/Artist.asp?ArtistID=49550&Akey=48347V9L&ajx=1#!asset84386

Upcoming Exhibition: The Color of Water at The Griffin Museum of Art, December 2022

LANZA: How has working in Monet’s Garden affected your art?

SCHORR: There is so much to observe about the life cycle in the Monet’s Garden. He donated his large lily panels to Paris after WW1 as a symbol of peace. As I photograph, paint, and interview the gardeners, I think about the garden as a reflecting pool for peace, light, and colour. I am in the process of interviewing all the gardeners, trying to understand how they plan and care for such an artful curation of plant life. Manu, one of the water gardeners, told me that working daily by the water makes him aware of the fragility and beauty of nature. Working in Monet’s Garden, I think I am starting to attune to this fragility, a quieter way of seeing how color shifts over hours and how plants move in relation to the light. Since first coming to the garden, I even feel like I am walking differently in the garden in that I am more aware of where and how to walk with less harm. In my work, I am exploring this gentler way of approaching our natural environment as a type of peace work.

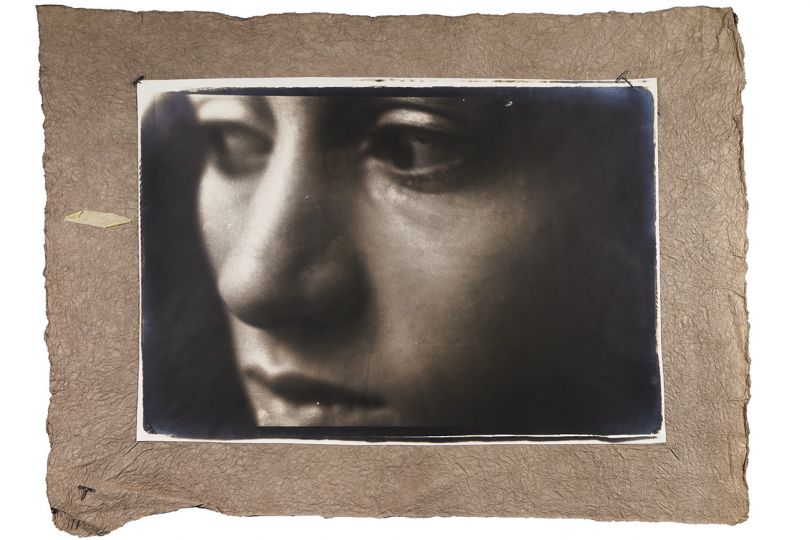

LANZA: Discuss the new series of photography including the creation of the mixed media, cinema graphs?

SCHORR: Three things repeat in my mind while I make my new work: 1. Seeing is an impermanent practice. 2. Like water, photographs are never truly still. 3. Love is longer than time. Before making the cinemagraphs, I researched Monet’s process of creating his gardens and lily ponds as a living color laboratory. With a particular interest in Monet’s experience of the impermanence of visual acuity. Changed by love and loss and time, Monet was destabilized by the way loss altered his vision, ultimately and arguably. In my time in Monet’s constructed garden, my work interrogates, mourns, and celebrates the structural changes to the architecture of our eyes over time. How do devices and procedures developed to combat that physical degradation affect our perceptions of color, light, and space? How is seeing changed by love and loss?

LANZA: Your work has evolved from painting to the photographic arts and over time into the subject of water, how did this happen?

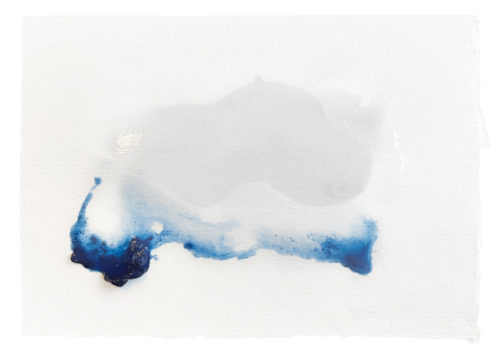

SCHORR: I love water. I love the fluidity of mixing paint and I’ve always love painter’s palettes and color mixing. My uncle was a messy painter. I remember thinking that his tools–paints, inks, and even silverpoint–were mesmerising. But I am also interested in emerging photographic technologies and how they can make the photographic process lighter and innovatively dynamic. I try to use photoshop and programming with a light touch so that the focus is the idea, even if that idea is as tactile as the sensual quality of wet paint. Using paint and emerging photographic tools together, I can record how paint looks when it is most vibrant. The active quality of paint resonates with water’s elusive ability to flow through life between the joyful and difficult times. I am drawn to the mystery of water.

LANZA: The Color of Water: The Algorithmic Sea, invites the viewer to contribute through your website, what have you discovered from this involvement?

SCHORR: For me, one of the exciting aspects of working on The Color of Water: Algorithmic Sea is that it is both a net-art and physical installation. Together with my collaborators artists/researchers/creative coders, Carlos Oliveira, and Gabriel Pereira, we can adapt versions of this work to the particularities of where we physically install it. For example, in our recent exhibition at the Northern Photographic Centre in Finland, local snow melted into the pool that we built for it. In this way, we invite people and the landscape into the conversation about the sociotechnical perception of color, especially how it is actualized through computer systems and their algorithms. The sea of colors shown in the installation is composed of a multitude of user generated colors. These colors undulate between the user and computer algorithmic processes in different site-specific iterations… so, like water, the artwork is always changing.

LANZA: Discuss your latest project, The Fragility Laboratory?

SCHORR: My new project is called Fragility Laboratory. It consists of both the cinemagraphs and a peace journal. The cinemagraphs are ovals quivering with small movements that evoke the feeling of a breathing landscape; these cinemagraphs reflect on the quality of near stillness in Monet’s water garden. Each cinemagraph is created by digitally stitching painted and layered photographic images together to encapsulate a shimmering moment of time. The peace journal involves gestures of paint and fallen flowers from Monet’s Garden. Each study is a meditation on an ephemeral moment inspired by interviews with the gardeners from Monet’s Garden. The journal tries to capture the fleeting quality of light on a flower while recognizing that color, like our emotions, is always in a state of fluctuation.