One hundred and fifty years after the death of Ulysses S. Grant history has begun to vindicate this great, yet often maligned, general. A humble man of striking insight, Grant is finally appreciated for the steadfast leader and visionary President that he was.

This iBook is a contemporary photographic tribute, by Charles H. Traub, to Ulysses S. Grant’s legacy and his immeasurable role in saving the Union. The issues confronted by Grant, in his deeds and writings, offer fresh insight for a country still divided politically.

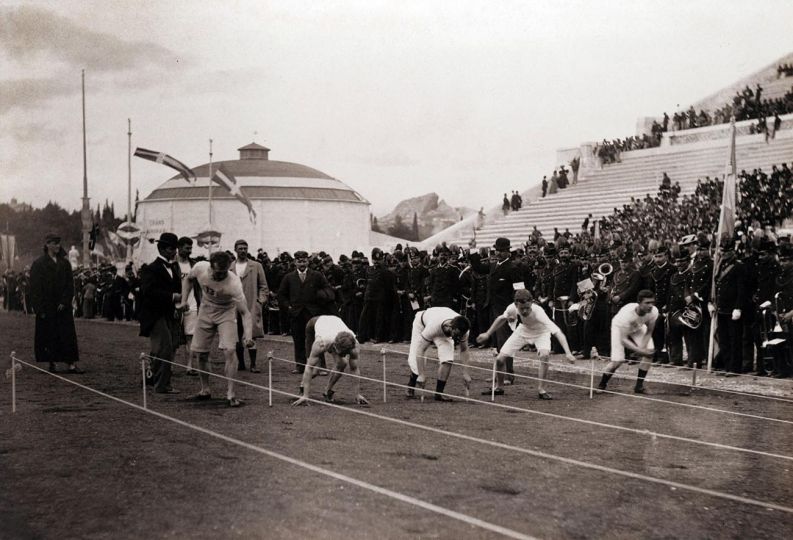

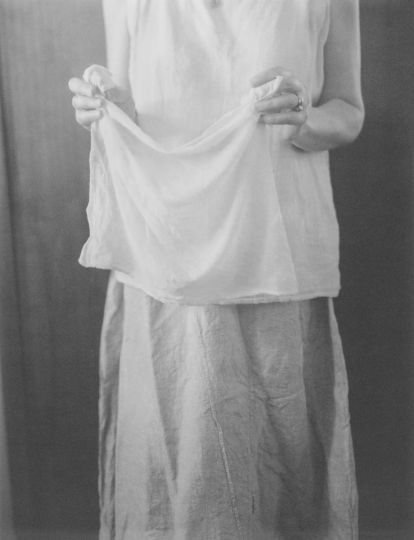

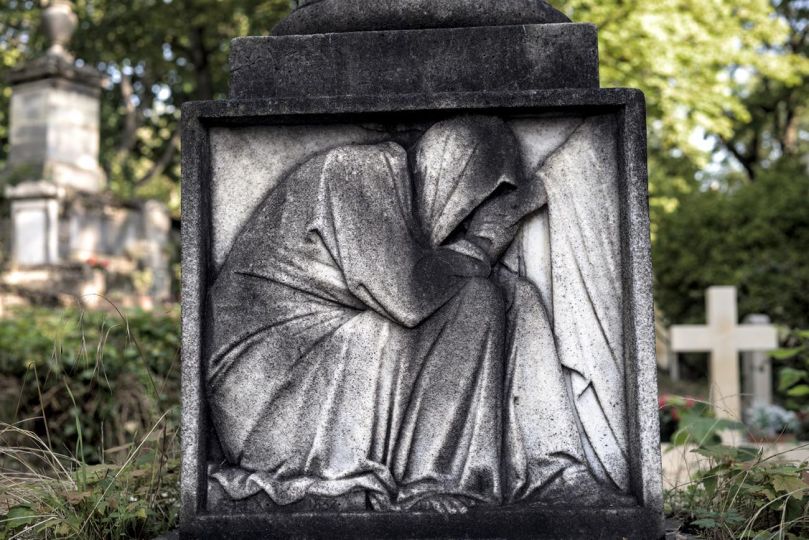

Charles H. Traub’s compelling and haunting photographs capture, metaphorically, the essence of those places made great by Grant’s indomitable spirit. Traub traveled throughout the United States photographing the major sites, homesteads and memorials marked by Grant’s life—from his childhood in Ohio to Grant’s final days in New York.

This iBook allows a unique personal experience for the viewer- a responsive exchange between image and text. The experience is heightened by the voice of the talented Edoardo Ballerini, who brings Grant alive, reading excerpts from his Personal Memoirs. Grant’s writings are considered one of the great pieces of American non-fiction literature. No Perfect Heroes is a singular synergism of art, history, image, sound and interactivity offering a sensory experience into a remarkable man’s story.

“The fact is I think I am a verb instead of a personal pronoun. A verb is anything that signifies to be; to do; or to suffer. I signify all three.” – Ulysses Grant, note to his physician, 1885

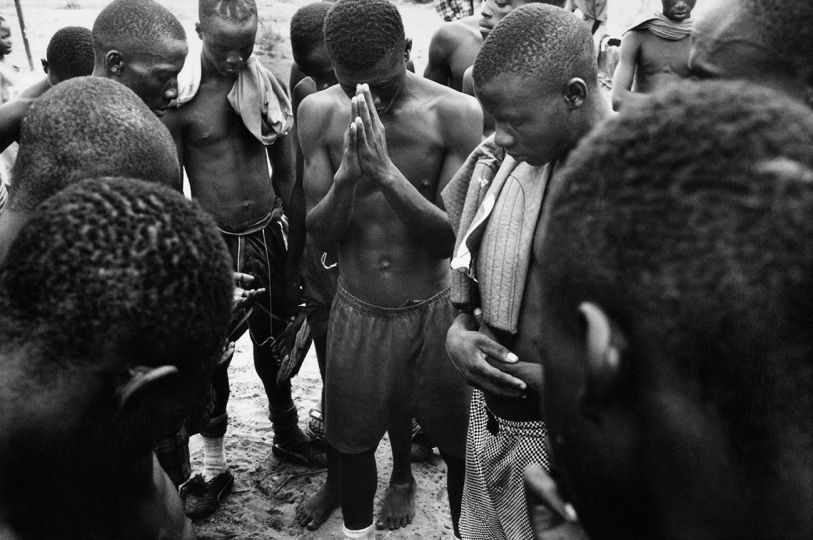

Charles Traub’s No Perfect Heroes takes its place in the library of contemporary books that deal deeply with the great theme of our time: what it means to remember in the aftermath of collective trauma, and to forget. These are dignified and un-ironic photographs, although often humorous, that present an irresolvable moral dilemma. Do we bury the past in order to escape becoming its hostage, or do we keep it alive in order not to repeat it? Is the legacy for the living rancor and shame or amnesia?

The only possible answer is both. The phrase “never forget” carries with it a demand for justice and a desire for permanent restitution that can never be met.

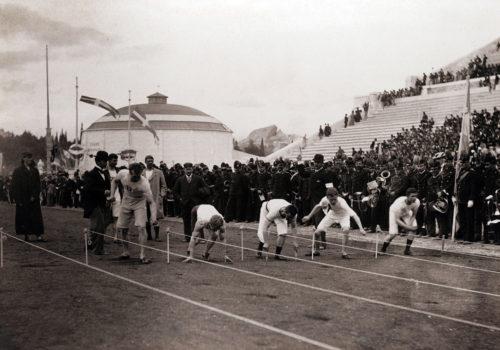

The world is so haunted by inexplicable fratricidal war- in Colombia, Malaysia, Rwanda, Cambodia, China, Old Europe, the list goes on – that it is convenient in the United States to overlook our own period of national self-immolation. Narratives heaped in myth about the Civil War diminish its two salient facts: 620,000 lives were spent in a conflict tat finally left all the maps unchanged, and the core issue was nothing more noble than the expedient of enslaving human beings. What is a proper memorial for this unsuccessful rebellion? Silent canons? Bronze statues of horsebacked generals? Traub’s eloquent pictures survey many Civil War sites in order to propose that there is no proper or perfect form of remembrance, because all memorials are historical expressions and all succumb to time. The grounds of an antebellum courthouse become a perfect place for skateboarding. The beautiful, patient grass of a broad field mocks the blood that watered it so long ago. The most striking thing about Traub’s canons in a pastoral landscape is not their duplication of the lines of sight toward a distant enemy but the silence of no enemy at all. And of course, in so many of the photographs, people are taking photographs – not to capture a sense of the past but to confirm their place in the present.

The frame for this meditation is General then President Ulysses S. Grant. He is the perfect subject, if imperfect hero, because he above all embodies the contradictions of history and remembrance. Traub tracks him through his memorials, from those at his Ohio birthplace to Appomattox Courthouse and beyond. Grant is easier to forget about than to engage because he is neither tragic nor romantic. On both sides of the war there were a dozen generals more dashing. As a tactician he was relentless rather than inspired. Unlike Robert E. Lee, an officer’s commission was not for him the confirmation of aristocracy but a sign of commitment to a task. He worried more about shoes and horses than he did about his reputation, which is one of the reasons his side won. No commander who prosecuted such a ferocious war was ever more committed to preserving a sense of humanity. He knew, above all, that savagery in war and exultation in victory keep open wounds that time should seal up.

We know all this about him because he wrote. His direct eloquence in his memoires conveys a person who cannot be reduced to mythic formulas or elevated to martyred sainthood, and so is without the cenotaphs of a Lincoln, a Washington, a Kennedy, a King. Traub uses Grant’s words as counterpoint to the images, a contrast that is meant to complicate our response in the best possible way, the way Shakespeare would have done it. A reflective man speaks to us of the impressions of war and at a deeper level attempts to retrieve them from mere horror and folly. This is Grant’s true heroism, and something that can be done only in words. Meanwhile, for us the living (as Lincoln put it), we visit the sites, we fish by the rivers, ignore the statuary, take more photos, and fail to remember what none of us can know. It was so long ago. Is it a comedy? Is it a tragedy?

Lyle Rexer

Charles H. Traub : No Perfect Heroes

iBook : bit.ly/chtraub