Three decades in the making, the J. Paul Getty Museum will publish a catalogue of the complete work of the American photographer, Carleton Watkins. His reputation long in question, this rigorous 19th-century aesthete found a champion in the renowned curator, Weston Naef.

“Carleton Watkins is to photography what Cézanne and Van Gogh are to painting,” proclaims Weston Naef, curator emeritus of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s photography department. “This man was probably the greatest American artist of his era, and hardly anyone has heard of him.” Indeed, it’s unlikely today that the artist’s name would elicit much response from the proverbial man in the street, but in his time the photographer enjoyed a certain celebrity.

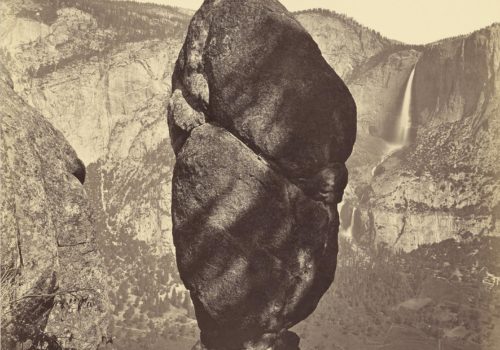

Born in 1829, Watkins first made a name for himself with his photographs of Yosemite Valley. These photographs would first influence Congress to pass a bill for the area’s preservation. If this is his most famous series, it is far from his only one. California landscapes, San Francisco street scenes during the Gold Rush, portraits of miners at work: from 1890. Watkins was the first to turn his enormous camera, known as the “Mammoth Camera,” on the American West. For commercial and non-commercial assignments alike, the New York native arrived on site and tried first and foremost to capture its spirit. “He really thought like an artist,” explains Naef.

Watkins printed large negatives on glass plates—a method that would become his trademark— and sold his photos in walnut frames so they could be hung like paintings. According to Naef, “Watkins’ was essentially the first to decree that a photography, like a Renaissance painting, should be printed large.” Conscious of the artistry in his work, Watkins signed his photographs, exporting them by the hundreds to Tokyo, Stockholm, London, Paris and New York, where most of them remain today. They have an undeniable historical character, meticulously imagined and elaborated, underpinned by an invisible network of interlacing lines. “If you create a diagram of the image,” says Naef, “you will notice that every element is unified, from the background to the foreground, like a Cézanne. Cézanne was a painter of color and of perception, and Watkins was a photographer of perception.” Of this perceptive body of work, only one negative survives, the rest destroyed in a fire caused by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

The massive book published today presents in ten chapters nearly every single photograph taken by Watkins. Of the 1,273 photographs in the catalogue, at least one copy was (necessarily) recovered. For a third of the photographs, only one copy exists. For another third, two to five copies exist. And for the final third, six to thirty copies are extant. “That’s not much,” says Naef. Gathered throughout the world, Watkins’ photographs have found their place in institutions not due to his reputation, but through their sense of observation.

For Weston Naef, the story begins in 1975, when the curator of the Metropolitan Museum of New York organized the exhibition Era of Exploration, which brought together the work of five photographers. Eadweard Muybridge, Timothy O’Sullivan, William Henry Jackson, Andrew Russell and Carleton Watkins. Naef realized that Watkins was rarely included in exhibitions and histories of the same era, and little represented in photographic encyclopedias. “As soon as I saw his photos, I couldn’t believe to what extent Watkins was underestimated,” Naef recalls. He embarked on a research project that would occupy the next thirty years of his life, fifteen of which were devoted to the preparation of this catalogue. “Nobody had gone to the New York Public Library to see a series of photographs that had been gathering dust for ages,” explains Naef. « There was no archive, properly speaking, like there is for Cartier-Bresson. There was nothing, not even the tip of an iceberg. »

Albeit a precursor of technical photography and endowed with an aesthetic sensibility at least equal to his more celebrated peers, it has taken Carleton Watkins more than a century to see his complete works published. It is a body of work that represents the beginnings of a new style of photography, one cherished by all the great photographers of the 20th century. “Watkins had two cameras, the ‘Mammoth’ and a smaller one, also on a tripod,” says Naef. “It was a sort of 19th-century Leica, perfect for snapshots.”

Jonas Cuénin

Carleton Watkins, The Complete Mammoth Photographs

Weston Naef and Christine Hult-Lewis / J. Paul Getty Museum

November 15, 2011

608 pp., $195