They are called Paparazzi and they are proud of it , they are right they are the best. A book ‘Famous‘ and two exhibitions are consecrated to them, the introduction of the book is by Philippe Garner director of the photography department of Christies. It is a small treasure.

Shooting ever-moving targets

by Philippe Garner

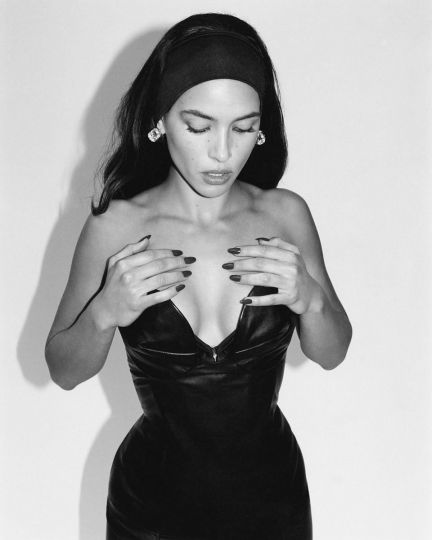

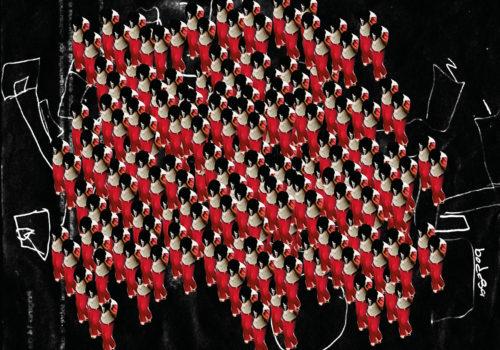

They prefer to maintain a low profile. Their role is not to build their own reputations in the public eye, but to consistently deliver to the press the telling pictures and picture stories that will define key moments and significant chapters in our history. They realized early on that to fulfill this objective their best strategy must be to preserve their own anonymity, always melting, chameleon-like, into the background. One of the principal themes that they have explored – and the focus of this book – is that of celebrity, of the ambivalent territory in the popular consciousness occupied by the glamorous, the talented, the powerful and the notorious. They are sometimes labelled paparazzi, though the term is limiting; it denies their range and has acquired too pejorative a flavor, far removed today from the glorious era of Rome in the fifties – ‘Hollywood on the Tiber’ – that gave birth to this professional label for the exuberant generation of photographers who helped stimulate, in a more Innocent age, the obsessive fascination with the lives and loves of a pantheon of glorified personalities of every stripe that has come to define the modern media.

They are Bruno Mouron and Pascal Rostain, two savvy and experienced photo-reporters, as they understandably prefer to be known. Paris-based, but ready to travel anywhere in the world for a scoop, they have worked together as brothers-in-arms for many years, since coming together in the late 1970s as contributors to one of the most respected picture-led magazines of the post-war era, Paris Match. In 1986, they set up a formal partnership, founding their independent agency, Sphinx. While the majority of the pictures presented in these pages are their work, a few, notably those of Bardot by Philippe d’Exea, are by their agency associates.

For Mouron, the spur to take up the profession was a 1970 book Les Reporters by Christian Brincourt and Michel Leblanc. The lure was the adventure, not the aesthetics of photography; the appeal was in the challenge of planning a trip to track a subject and of working against the odds to bring back the pertinent pictures. Speed and patience, ingenuity and adaptability, and a certain native cunning were essentials, as was the instinct, in that often all-too-brief encounter with the target, to press the shutter at the precise moment when the look, the gesture and the context were most perfectly aligned. With ever-moving targets there is no second chance.

For Rostain too, it was the hunger for adventure, stimulated by his recent military service, that inspired him, in 1978, to travel to Chad to document the civil war raging there. His imagination had already been stirred by the example of such pioneer photo-journalists as Erich Salomon and Weegee, and, as he explains with pin-point accuracy and not without humour, by the model of that intrepid journalist and adventurer Tintin. No wonder the language that the photographers find themselves using to describe their status and their methods is that of the big-game hunter, the spy or the commando rather than that associated with the conventional practices of photography. They refer to themselves as ‘mercenaries‘, ‘Zouaves‘, ‘snipers‘, and they explain that as young men they typically wanted to be Zorro, or James Bond.

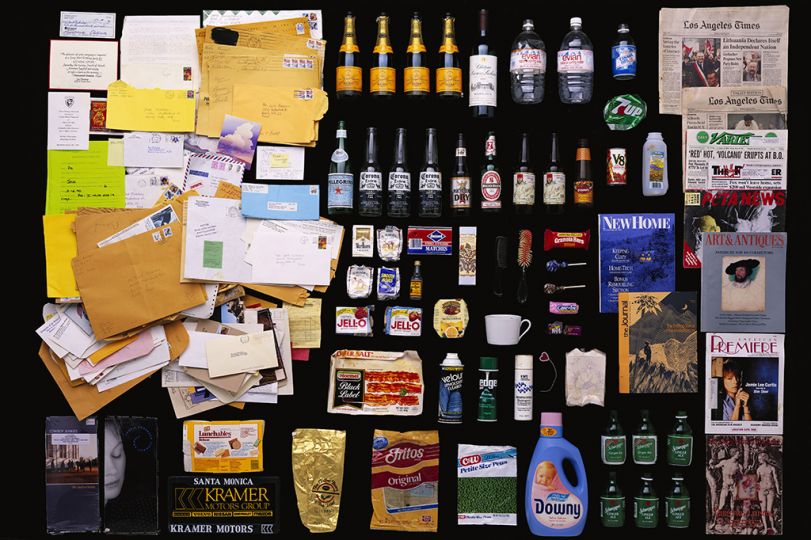

Mouron and Rostain frequently worked undercover and an assignment could involve days, even weeks of scouting and subterfuge to create the opportunity they needed to home in on a moment of truth. In other situations they had to become invisible in plain view, by winning the trust and acceptance of their subjects, and so become unobtrusive. While there could be a degree of accommodation on both sides, never would they allow their subjects to orchestrate the situation. Their pictures, which are always about people, are authentic documents that ‘relate an era,’ they explain, and illustrate with integrity and directness the facts of public and private lives.

Among the reportages of which they speak with special pride are the numerous picture stories created for Match that document those on the fringes of society, the marginal characters such as prostitutes, transvestites, and those whose lives are destroyed by the culture of hard drugs. Their work is about lives lived in extreme circumstances. At the other end of the spectrum, they capture the sheer magnetism and charisma of great stars. Or in their sights might be the hypocrisies or vanities of politicians and other public figures. In this respect their role has something in common with that of the slaves in ancient Rome whose task was to ride in their chariots alongside returning heroes during their triumphal parades and to whisper constant reminders of their status not as gods but as mere mortals, like the crowds that were applauding them. From the age of the Caesars to the era of La Dolce Vita, Rome has long been witness to the dangers of elevating humans to the status of gods.

‘Famous‘ is an apt title to resume one key facet of the duo’s activity, one that is explained by the collective perennial public appetite – perhaps even primordial need – for heroic figures to idolize and analyse, figures through whom millions can celebrate an ideal of glamour and of high-visibility achievement that history tells us often comes at a substantial price. It is in this world of wild possibility that our image-makers capture the pictures that become universal visual metaphors for the lure, the apparent thrills and the undoubted frustrations of those enjoying, often trapped within, and sometimes ultimately consumed by the mythologies constructed around them.

The conventional history of photography has tended to give primacy to those practitioners with lofty artistic ambitions for the medium, to those who would have photographs aligned with the fine arts as sophisticated vehicles of creative expression. Curators and critics, and indeed many photographers, have also stressed meticulous mastery of technique – of exposure, development and fine printing – as essential to the ultimate fulfillment of the medium’s potential. Our protagonists are more pragmatic and see the truth and authority of the image as fundamental, fastidious technique as window-dressing. They perceive a precious concern with aesthetics as a potential inhibition within the methodologies that they must apply.

’We would frequently guess our exposures and trust in the wide latitude of Tri-X,‘ explains Mauron, staking out an alternative perspective on what matters within their work. And we, their audience, in turn find ourselves drawn to the irresistible visual logic of this important facet of the history of photography, one all too often overlooked by many of the medium’s supposed champions. Here is a raw and dramatic genre in which the authentic spontaneity and the immediacy of the subject are all, and in which the texture of grain from film pushed to its limits in low light, the sometimes shallow depth of field dictated by a necessarily long lens, the blur of movement, or the drama of tight framing or randomly layered structure can all contribute to the energy and ultimate success of a compelling and memorable image, one that could never have been achieved through pre-planning. ‘Famous‘ challenges us to recognize, appreciate and celebrate a fresh frame of reference by which to assess the credentials of a great photograph.

Famous – Bruno Mouron & Pascal Rostain

From September 6th to Octobre 27th, 2012

A.galerie

12 rue Léonce Reynaud

75116 Paris – France