At the Centre Pompidou, the exhibition Corps à corps offers an intelligent and powerful rereading of photographic history through the prism of two collections, the collection of the museum in dialogue with the collection of Marin Karmitz.

Summarizing the history of photography is a vain and inexhaustible attempt. Works have tried it with more or less success. Encyclopedic copies faced with detailed, sometimes brilliant readings such as A World History of Photography by Naomie Rosenblum, national and historicized approaches such as 50 Years of French Photography from 1970 to the Present Day by Michel Poivert, short and luminous essays such as A Little History of Photography by Walter Benjamin or La Chambre claire by Roland Barthes, and more recently, numerous feminist works offering a history of art freed from its shackles (Women Photographers directed by Clara Bouveresse or A World History of Women Photographers by Luce Lebart & Marie Robert).

The literature on the subject is plentiful, without ever exhausting (yet) the subject of technical inventions, the adventure of photojournalism, of sensuality which is also adventurous, of formal jostling, black and white school of thought against the ineptitude of color, until the recent transformation of the image into a permanent flow. Books and exhibitions alike provide insight into a gigantic history formed in such a short time, barely two centuries, so few years for an old art. This is the strength as well as the pitfall of this medium: following technologies and economies, being both the prerogative of an art and a pastime of leisure.

On the walls of museums, the exercise has been attempted more than once. The exercise of collections often remains the prism of a particular history, a reflection not only of the institution, but of the sensitivities of each. The one currently offered by the Center Pompidou is anything but exhaustive – and this is a pitfall skillfully avoided. It demonstrates common sensibilities specific of the two collections, those of the National Museum of Modern Art and that of collector Marin Karmitz. Subtitled History(s) of Photography, it aims above all to show how humans were and are represented in the 20th and 21st centuries through photographic work.

Let us first explore these two entities that are one. The collection of the National Museum of Modern Art is undeniably the richest in France, if not in Europe, in terms of numbers. With nearly 45,000 prints and 60,000 negatives, it covers the major movements of the defining decades of photographic history – from surrealism to constructivism – while being attentive to recent creation. Its large collections (László Moholy-Nagy, Brassaï, Eli Lotar, Man Ray, Gaston Paris, Sabine Weiss etc.) also demonstrate some shortcomings and weaknesses, the collections being unfortunately often looked at in terms of what is not there.

The collection of Marin Karmitz, an activist filmmaker in the 1960s and 1970s, a key figure in European cinema, is found in much smaller numbers. 1000 prints constitute, in the face of a public collection enriched by donations and acquisitions, a very ridiculous comparison, which must be judged for the quality of its selection and in the conduct of an individual gesture, that of an informed collector, with enlightened fascinations.

Here public and private views complement each other more than oppose each other. It is a face to face without any opposition being thought of, or rather, a complementary story without exhaustiveness or generality. Designed by curator Julie Jones, Corps à corps aims to reveal common fascinations, if not obsessions, which are revealed both in the public collection and with the private collector.

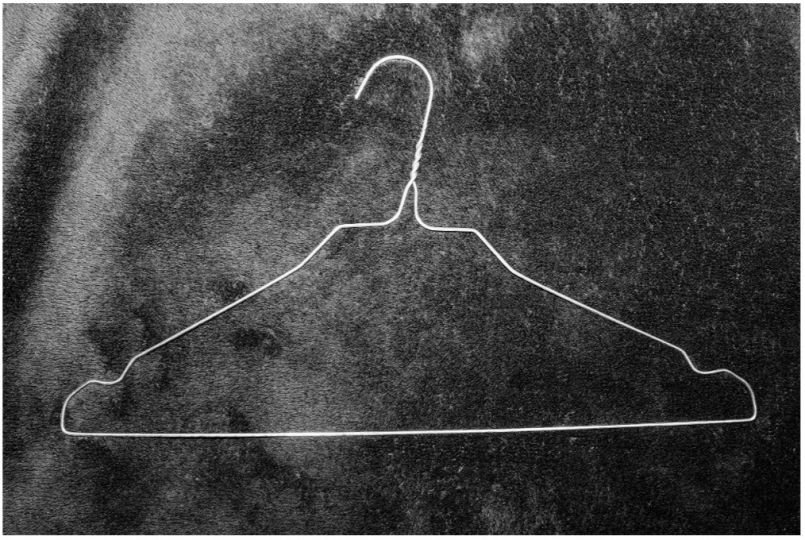

The exhibition is divided into chapters presenting a vocabulary as specific to the human figure as to the photographic field itself: premiers visages, automatismes ?, fulgurances, fragments, en soi, intérieurs, spectres. The body is a very contemporary subject, as are identity or intimacy, but this entry point seems the most natural as humans first turn their lens towards themselves, if not towards the other, at least towards the flesh, a face, an emotion.

The dialogue begins with a series of faces, including studies often ignored in the work of the sculptor Brancusi, striking in their realism and anguish. Showing the other, making them exist, taking them out of their anonymity, representing them comes before any other gesture through their face. Paul Strand’s Ian Walker, South Uist, Hebrides (1954) is one of his immediately eye-catching portraits, which sheds the historical markers inherent in each photograph, anchoring in a vivid feeling an inherent gripping to the viewer.

Further on, the Fulgurances chapter returns to the hunt for the immediate, to fleeting impressions, to the capital letter of the anonymous. These are the worn faces of the workers of the New York metropolitan area of Walker Evans, and then the views of Brassaï, wild Parisians who in the eye of the photographer-hunter show humans in their complete relaxations, when it is nothing more than self or appearance.

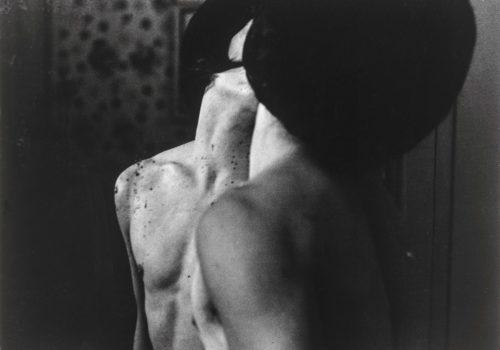

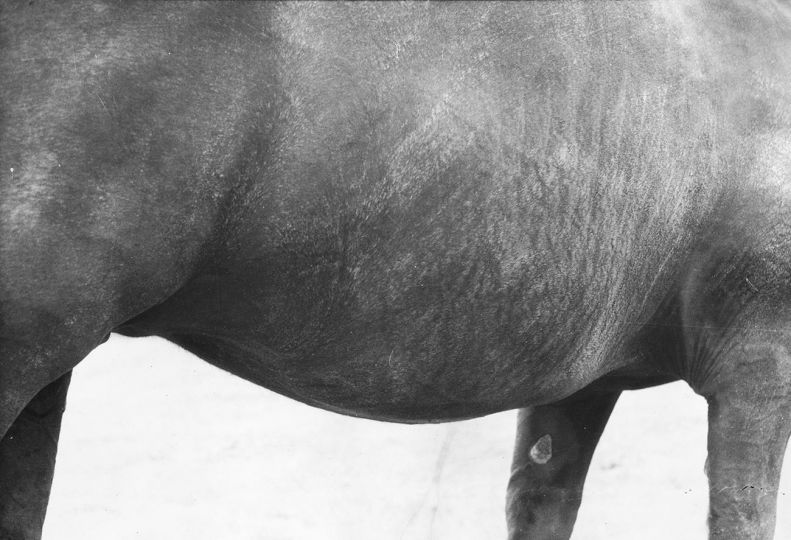

And then there are these body parts, these bits of muscle and these barely perceptible silhouettes. This is the Framents chapter, which could also have been called Fugaces and which gives free voice and heart to the play of compositions as well as to the fascination of details. It’s this Canopée by Saul Leiter (him again, how can I escape from him?) and above all the glistening muscles brandished like clubs from Riveteuse pour navire by Jakob Tuggener (1947).

Let’s skip a few more chapters, let’s not follow the lines, because basically, the exhibition in its last moments shines, fascinates, moves, overwhelms again and again. There is the pleasure of revisiting the San Clemente series by Raymond Depardon on psychiatric confinement and its excesses and its counterpart, Pigalle and its nyctalope madness by Christer Strömholm with the series “Les amis de Place Blanche”. There are still the specters, the ghosts, the silhouettes, the apparitions, the doublings, the play of reflections which do not exhaust the figures of speech, of the specter part. A whole world of doublings and reflections, which says in conclusion that the human figure is never what it is, is never representation either, but rather the in-between of a fiction and a the truth.

One more word, one last. Corps à Corps proves to be a partial reading of photography successful in its selection as well as in its scenographic play. The spaced dialogue between the works is elegant in its pearl gray walls and the play of mazes, chapels and interiors give the lasting impression of a dive. That of our interiority? That of a story that opens up and sucks you in?

Arthur Dayras

Corps à corps.

Histoire(s) de la photographie. Collections de photographies du Centre Pompidou – Musée national d’art moderne et de Marin Karmitz

Curators : Julie Jones, curator at the Photography Cabinet, Mnam-Cci with Marin Karmitz.

September 6, 2023 – March 25, 2024

Gallery 2, level 6

Centre Pompidou,

75191 Paris cedex 04