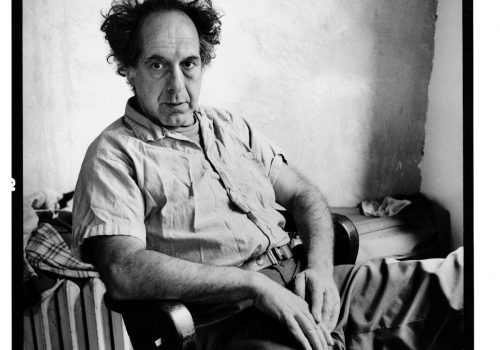

Arnaud Claass’s Essay on Robert Frank, published recently by Filigranes Editions (2018, 160 p.), Presents a multi-faceted reading of the work of this great artist of Swiss origin. Anxious to renew the approach with various tools, he also strives to replace Robert Frank most famous work, The Americans, not only alongside his other editorial masterpieces (including The Lines of My Hand, reissued last year by Steidl) but in the context of a creative adventure spread over a total of more than sixty years. The considerable influence of his films on independent cinema is also widely discussed.

The excerpt we publish below discusses the alternation, from 1971, between the phases of Frank’s almost wild withdrawal into his isolated house in Nova Scotia and those of immersion in society (teaching, commissions, movies). Struck by the misfortune of the disappearance of his daughter Andrea in a plane crash and the incurable illness of his son Pablo (who was to die in 1994), he gave his photographic and cinematographic work a stylistically different turn, more and more meditative. Inspired by such great literary figures as Robert Walser, he tended to melt life stories and formal inventions, deploying a feeling of self as a narrative perpetually restarted – without denying his curiosity for the world or falling into the banal narcissistic introspection.