Synonymous with the art of travel since 1854, Louis Vuitton continues to add titles to its “Fashion Eye” collection. Each book evokes a city, a region or a country, seen through the eyes of a photographer. With Kyoto, the photographer Mayumi Hosokura explores intimacy in two different ways, both of the city and of herself, in wide tones of blue.

Since the creation of the collection in 2016 and the publication of the first opuses, the Éditions Louis Vuitton and the graphic designers Lords of Design have created a warm collection. Each new release proudly supports a new colourful cover. The artist and author are elegantly named at the top of the page, in a dark textured label followed by a small photograph. This insert announces the next pages, the story that is to come, the promised journey. The touch of the cover has a satin texture. On the back, a huge photograph closes the journey. The shell here is beautiful, always beautiful—when a book is beautiful, one must repeat it, to be blissfully ecstatic about it, again and again—and the expectation of one book after another gives the promise of a new pastel, of what the opening slide will be.

This is the nature of a collection: once it is established, it does not move, if at all. Just think, the most beautiful book collections are also the most classic. Once the lines are fixed, they don’t move. In France, there is Gallimard’s “Collection Blanche” which makes the scribbler salivate with envy, “Photo Poche” in its serious and intriguing all-purpose format or, less well known and more whimsical, the dancing lines and letters of Éditions Cent Pages. The surprise sometimes comes with the opening, with the osmosis of finding a book that makes sense with its touch as well as its sight. A synesthesia of the page, if you prefer.

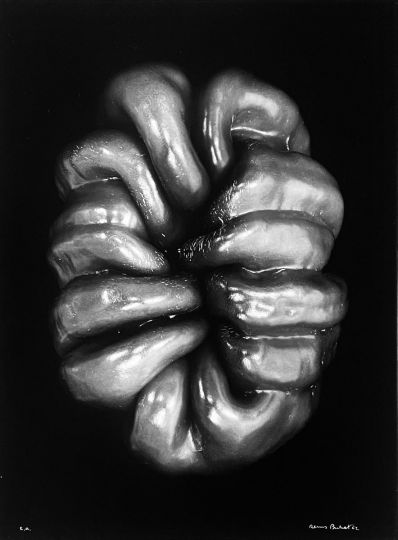

Mayumi Hosokura’s Kyoto is one of these. To the suspended, levitating shots of the Japanese photographer, the chosen papers respond with a kind of lightness, sparingly scattered. On the one hand, a paper with light glittering reflections on which Hosokura’s works are printed, on the other, a thin vellum blackout paper that veils some of the duplicates like a sliding panel. The combination of the two papers unconsciously contributes to the intimacy of the book. Most people will touch one page and then the other with their finger. One will not notice anything. Others, like me, will try to find the recipe. Should we ignore it? Does giving too much technical detail seem boring ? To know is not to deceive, the enchantment remains there, in the air, on every page.

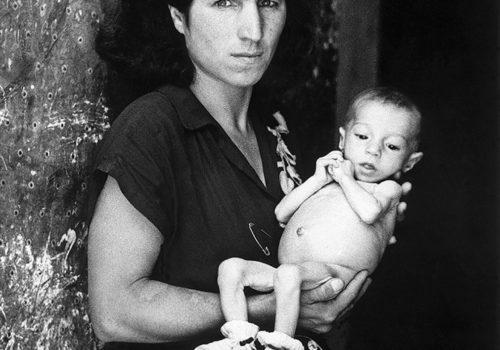

This would not be possible without Hosokura’s work. The whole book is built on a short palette, from midnight blue to imperial greens. There is a kind of aura about the whole, an ode to the night, to the unchanging but brief silences (Candles and Foxes), to the agitation of a city caught in reverse of its convulsions (View from Yasaka Shrine), to the quietness, everywhere, down to the repeated, forgotten gestures of our body (Pink, Higashimaya-ku). The photograph is an instant, it struggles to get out of the frame and arrives at nothing more than a little bit of a second. “It crystallizes a single moment from the world forever ”, Hosokura points out; its power comes from its articulation, its melody. An image can produce a sound, and together form a silent composition. From all this blue, there is a symphony.

Others before Hosokura have written in colour. Irma Blank refused words to draw meaningless lines. Gillo Dorflès called this asemic writing, that is to say writing “devoid of meaning”, turning away from reason. The motifs, lines and scribbles form a language in themselves, a refined visual force, a vocabulary of intuition, of raw feelings. It is curious to note that her drawings (or writings, depending on the point of view) are mostly blue. In this register, Yves Klein is an obvious choice. Although it may be trivial to mention him, it should be remembered that Klein also sought through the prism of colour and monochrome an elevation, a lightness, allowing the viewer to merge entirely into a whole. Firstly, he used red, orange, yellow and pink in his monochrome paintings, then blue evokes the azure as well as the night, a form of invitation to contemplation, sometimes deep and sometimes light.

Hosokura speaks of “the action of photography” as a “musical — to look at all of the details of one photograph as one moment in your own head”, when Irma Blank sings a song without words, or Yves Klein composed his Symphony-monotone (1947). In each of them there is a search for a chromatic language that is above all emotional. It doesn’t matter that Hosokura’s photographs are identifiable, that her pictures are representation—here a tender face lost in thought, there the flames of a restless fire.

Basically, the story of Kyoto is quite simple to tell. It’s a wandering through “a very spiritual city”, where temples and rituals blend with illuminated avenues. There are beautiful faces, surprised after having danced. An old man is absorbed reading his newspaper. There are still textures, petals white as lime on water, shadows dance and shimmer on the walls, foliage in the light. Sounds and scents swirl in the evening air. It is the harmony that counts, and its song palpable to the eye.