Andy Summers, acclaimed guitarist of The Police, the top rock band in the world during the 1980s, who gave us the haunting guitar riff in the song Every Breath You Take, now considers himself a “wanderer” with a Leica camera in hand. As he distances himself from his past glory and glamour, he seems to be drawn to roaming farther away from London, New York, and Los Angeles. Revisiting the Zen literature he discovered when he was younger, his predilection for traveling has taken him to Tokyo, Shanghai, Bali, and, as he says, “to the back alleys of Hanoi”, where photography becomes a way to extend his innovative musical creation and research, an essential path (the Dao) to explore his own growing old.

The Bones of Chuang Zhu the title of Summers’ current exhibition at Anne-Cecile Noique Art in Shanghai and an upcoming book, appears to be a reflection on the contrast between the musician’s present stage of existence and the remembrance of past turmoil. His title refers to an anecdote of Chinese thinker Zhuangzi of 4th Century BC, who came upon a skull on the road and debated with it the merit of being happily dead or of being alive with all the toils of the living world; the skull being the symbol of vanity and mortality, a universal theme in classic art. Yet it also implicitly expresses the photographer’s existential quest for freedom from the cycle of turmoil in his own life.

In the same spiritual pursuit as Zhuangzi, Andy Summers’ collection of instant snapshots captured during different journeys to China is remarkably personal, intimist and contemplative. He himself paid tribute to those who influenced him, such luminaries as Robert Frank, Ralph Gibson, Lee Friedlander, Diane Arbus, and Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Although not a single image of a skull or skeleton or bones can be seen here, his Zhuangzi pictures are at times reminiscent of Eikoh Hosoe’s wild fields in Kamaitachi, and at other times of Anders Petersen’s City Diary. One striking characteristic of Andy Summers’ shooting style is that ninety per cent of his photos are vertical ones; only a few are in “landscape” format. This places him even closer to Anders Petersen, both of whom are keener at painting “portrait”. Whether or not this is due to decades of holding his guitar this way, in fact, it is physically harder to hold a 35 mm camera vertically than horizontally.

The camera first became guitarist Andy’s third eye as an exercise in watching, when he began taking pictures in the early days of the band. “For me it started when I was with The Police in the beginning of the ’80s,” says Andy Summers. “The band was constantly surrounded by photographers. I was always talking to them about cameras. Eventually I got a camera. Quickly I found that I was obsessed with it. It’s like music to me, another form of expression.”

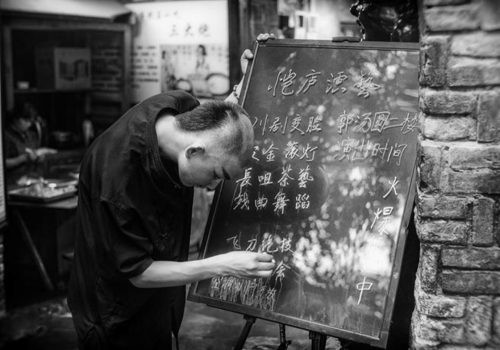

And he did not hesitate to call his 2007 photo book I’ll Be Watching You, which presents his intimate photographs of bandmates, roadies, and groupies on and off tour, all over the world. But in China, in his Bones of Zhuangzi series he turned to following anonymous people – and watching them individually, in Beijing and Shanghai and in remote places deep in the provinces. As a man used to facing an audience on stage and being in the limelight, Andy Summers is drawn to venues of performance, like the girls in black dresses showered with light in Beijing, or the backstage scenes in some folk opera plays in Sichuan. It was natural that as a musician Andy would become fascinated by an “Old men Band” he encountered in Lijiang, the Naxi Ancient Music Orchestra, especially by the ancient string instruments they were playing, more folksy and rustic than the common traditional Chinese musical instruments. His close-up observation of the old musicians’ faces, and of their strumming fingers, is an X-ray kind of attempt to scan their skulls, their skeletons, “the bones” that lie beneath, a poignant demonstration of the power of photography to freezes on paper the time that passes but not the cycle of life and death, for when he returned some time later to Lijiang he would sadly learn that most of the oldest musicians had passed away.

As Andy Summers himself is growing more “ancient”, the camera comes in handy as another musical instrument for composing his personal poems, his haiku, in a calmer and more reflective manner. His dreamlike uninhabited landscape, what he calls his Dreamscape of China, suggests metaphors and interpretation. It opens with a breathtaking panorama of the Yellow Mountain that is called Cloud Dispersing Pavilion. And then there is a mysterious promontory projecting into nowhere, a pathway in a cornfield like a parting hairline, and there, a waterfall as an abstract composition.

Describing his approach, Andy Summers says: “I walk around with my visual consciousness very turned on. It’s not always people’s faces. It might be the edge of a door or something on the ground. It’s the stuff that seems to sum it up—metaphors for the culture you are in.” He looks for signs and calligraphy, the way the light falls, and the texture to compose an image. “You feel, as you do it, that you retune your eye, your visual consciousness and you start seeing things.” a ghostlike ballerina’s costume floating in midair, the shadow and light playing on the details of some Chinese furniture, crystal lotus and flickering candles in a temple, broken hinges of an old wooden door. Musical instruments are seized here and there: a folk-style Huqin, a two-stringed viola with its resonant body wrapped in python skin, its scroll and pegs leaning elegantly against a celestial crane in flight; in a temple the close-up view of a copper hand playing the Pipa (Chinese lute), a detail from a statue of Heavenly King, one of the Temple Guardians. It is said that when this musician god plays his Pipa, his enemies are deafened and suffer excruciating headaches.

Andy Summers’ geometric compositions span out like musical partitions, while the stream of unconscious images weaves along like a silent movie being projected on a large screen, accompanied by a faceless musician who confounds the strings of his zither (the Yangqin) with the stripes of his shirt, in an unheard of atonal adagio. Strange portraits abound, like the young girl in the country carrying a stick across her shoulders with bundles of straw on each side. She is looking up at the photographer, apparently with a questioning expression on her face yet her hands rest comfortably relaxed, posed like an actor in a play. Is she real or fictional?

There seems to be some correlation between rock musicians and photography since many have taken up the camera and have had successful exhibitions with published books. Among the best known are Patti Smith (who was a close friend and companion of Robert Mapplethorpe), Graham Nash, Bill Wyman and the late Linda McCartney. However, this collection of “Bones” by Andy Summers is the best evidence of his unique stature among his peers. This exhibition will only lift a corner of the veil shrouding the mysteries of China, these “bones” encountered on the roadside by the wandering Zhuangzi aka Andy, surely leaving us hungry for more.

Jean Loh

Jean Loh is a writer specializing in photography. He lives and works in Shanghai, China.

Andy Summers

Du 13 octobre au 7 novembre 2017

Anne-Cecile Noique Art

Shanghai