André Ostier, a fashion photographer known for his work with the great fashion designer Christian Dior, sought to document a fleeting Paris by capturing its people, its buildings and the special moments of the city he admired. A book brings together 60 of these striking images that instill a certain sense of nostalgia.

When several grand Paris houses, like Le Palais Rose, the extravagant residence of Anna Gould and Boni de Castellane, were razed in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the photographer André Ostier sought to express his frustration and disappointment at the rampant demolition of 19th and early 20th century buildings in the city he loved. He was prompted to write a brief essay entitled “Quand le Balcon devient Fontaine…,” accompanied by a number of period Paris photographs. He was worried. Where, he wondered, would future readers of A la recherche du temps perdu be able to observe the proper setting of Marcel Proust’s cast of characters? Although he thought that the powers that be were right to protect the work of Art Nouveau and modern architects such as Hector Guimard, Auguste Perret, Robert Mallet-Stevens and Le Corbusier, Ostier saw things differently. He noted, “There were so many other buildings that gave Paris its soul. We have come to realize a little late that the visitors and foreigners who love our cities, and who at the same time appreciate modern solutions and intelligent embellishments, generally prefer houses that enable them to recall the past.”

André Ostier had a keen admiration for the city he considered the center of the world, if not the universe. Paris was to be preserved, since it provided a context that allowed its inhabitants to understand one another and adapt to their diversity. It was the environment in which they lived, and which defined their identity, their urbanity and their Heimat, all in one. During the 20th century, painters, sculptors, photographers, musicians, fashion designers, thinkers, and even politicians recalled the importance of an attachment to basic human values that founded and maintained relations among citizens. Through his photographic practice, André answered this call to action, this reminder that time presses, this incentive to reaffirm priorities.

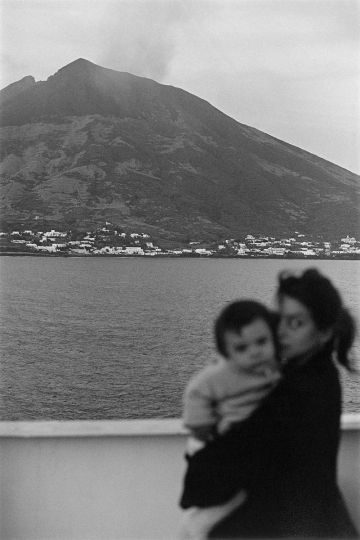

Born with a native curiosity, constantly on the lookout for unusual images, André Ostier was subjugated by photography and the art’s capacity to freeze time and frame space in such a way as to reveal “the unforeseen meaningfulness of ordinary things,” in the words of John Szarkowski, Director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York from 1962 to 1991. Ostier concentrated on what had changed, on that fleeting instant endowed with an aura of added value that makes it possible to see the ordinary differently. Whenever he looked back over his previous production, he would choose a number of images that he would ask the photographic laboratory to print in a larger size. He identified photographs of striking singularity, different in subject and approach, yet revealing the city’s true character, its immutability, its resistance to change, and its intrinsic resemblance to the past.

Judging from the organization of the contact sheets and the information contained in the images, many of Ostier’s urban studies date from the 1940s, although some are manifestly earlier. On the occasion of an exhibition of his portraits of artists at the Musée Bourdelle in 1982, he explained that after the Second World War, he hoped to publish a book on this theme, with the title Paris avant qu’il ne soit trop tard [Paris Before It Is Too Late]. Ostier even produced a mock layout, although there is no evidence in his correspondence, diary or notes of any contact with a publisher at the time. This initial choice of views of Paris was limited to 25, and they make up the core of this book. Yet the theme was deeply ingrained in André’s psyche, and he continued to create new contact sheets up until the month of his death, in January 1994. It thus seemed logical to complement the original selection with later photographs he had taken and earmarked for this purpose.

André Ostier followed carefully honed procedures as he developed his archive. As was his wont, he first composed thematic contact sheets in broad categories, according to place or date, such as Paris, Île-de-France, Cannes, 1940, etc. The individual contact prints were printed from square Rolleiflex negatives generally measuring 6 cm x 6 cm (2.36 in). The negatives are still kept in the small red cardboard notebooks the photographer decided to use to organize his archive. The notebooks then put into slipcases of the same color. The cardboard spine is stamped in gold letters with information about their basic purpose: Classic Film 6 x 6. The notebooks are identified by Roman numerals (the Paris notebooks are numbered XXII, XXIII, LXV, LXVII, LXVIII, LXXIII, and C), and each of them contains approximately 100 negatives classified with Arabic numerals, and protected by glassine envelopes. Each notebook starts with a numbered list on which the photographer could note the subject of the corresponding negative.

On the slipcase, Ostier would sometimes glue a small sticker with a brief description of the notebook’s content. To enhance the selection of photographs that made up the original version of Paris avant qu’il ne soit trop tard, Ostier printed larger images (approximately 22 x 28 cm or 8.66 x 11.02 inches) and then bound them in a volume loosely sewn with red thread. The book measures 29 cm in length, 22.5 cm in width, and 2 cm in breadth (L 11.42 inches, W 8.86 inches, and B 0.79 inches). In the top left corner of the faded brownish-green paper cover, his family name is written casually by an unknown hand in red-pencil capitals. There is no introduction or printed title. Yet from the first page, the subject can be immediately perceived, both intellectually and emotionally, since it occupies the same realm of understanding and feeling. They all represent the essence of the city in which the photographer was destined to be born and to die.

André Ostier sensed that a significant page in the city’s history had been turned. Many streets, avenues, parks, neighborhoods, mansions, and palaces had disappeared, as had many other public and private buildings. The avowed goal was to make room for continued progress in the name of modernity and Haussmannian continuity.

In 1939, war again threatened the city. Many of the Louvre’s collections, including the Venus de Milo and Michelangelo’s Slaves, had been shipped to the provinces, and historical monuments in Paris were subject to protective measures. By the end of the decade, Ostier had applied his newly learned skill as a photographer to capture attempts to save the proud yet fragile vestiges of the city’s former grandeur. From the war with Germany in 1940 and into the Occupation, Ostier’s photographs of sandbagged statues and monuments conveyed a sentiment of profound sadness, incongruity, and inevitability, while still representing beauty, proportion and style. For this reason, Michel de Brunhoff published several of Ostier’s images in January 1945 in Vogue Libération, the first issue of French Vogue after the end of the world conflict, to accompany a poem by Paul Éluard.

Outside the circle of knowledgeable Parisians and sophisticated visitors savvy about the ways of the world, André Ostier was, and is still today, an unknown photographer. This lack of renown is most likely the result of his being part of the world he captured on lm. His bourgeois background provided him with the financial resources to support and entertain himself. Born in Paris in 1906, he was educated at the Lycée Janson de Sailly from 1918 to 1924. He began to knit his social network. For example, he most likely met Christian Dior in the 1920s. They both attended classes at Sciences Po, France’s leading political science institute (Ostier for the school year 1924–1925, and Dior from 1923 to 1926). Neither graduated, however. Perhaps the two young men were more interested in the professional and leisure activities of the multitude of artists, musicians, and writers with whom they associated.

Ostier did his mandatory military service between 1926 and 1928 at the Inspection générale de l’artillerie, in the heart of the Faubourg Saint-Germain, at place Saint-Thomas-d’Aquin. From 1928 to 1934, he managed a bookstore–gallery on the Avenue de Friedland, called A.L.P., which stands for A LA PAGE, a play on words to signify that it was a happening place. There, he exhibited several of the day’s leading artists, such as Le Corbusier and Max Ernst. This gallery vocation was, indeed, in fashion between the wars. For example, in the same decade, Christian Dior managed a gallery in Paris off Rue La Boétie, which he had opened with his friend, Jacques Paul Bonjean. Several years later, Ostier became interested in journalism. With his friend, the writer and art critic Édouard Roditi, he wrote articles that were published in Le Figaro and Magazine d’Aujourd’hui, among others. André soon recognized the growing importance of photography. He bought his first professional camera—a Rolleiflex—in 1938, and took fashion shots for the French magazine Marie-Claire. The same year, he began a series of portraits of artists and writers that was to become one of his most successful themes, as he skillfully highlighted creative attitudes and atmospheres.

As always, André’s background and address book served their purpose well. His first sitter was the painter and art critic Émile Bernard, and by 1941, Ostier had established contact with several other major artists, principally in the South of France. Maurice Denis, who lived next door to the Ostiers in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, spoke to André of the Nabis, and provided an introduction to Aristide Maillol in Banyuls-sur-Mer. André visited Pierre Bonnard at Le Cannet, and Henri Matisse in Nice. They in turn spoke to Pablo Picasso. At the end of 1941, Ostier participated in a photography exhibition in Cannes, with Victor-Henri Grandpierre, Hubert de Segonzac, and Jacques Henri Lartigue, among others. In fact, Ostier had no need to prove himself. He had a keen eye and a sharp tongue. He thought highly of his own work and said so. For example, he was not reticent to inform visitors that both Pablo Picasso and Henri Cartier-Bresson had expressed their admiration for his portraits of artists.

The parallel with Dior came to the fore again after the Second World War. When Christian Dior was chosen to launch Marcel Boussac’s new fashion house, Ostier was an active participant. He became a major photographer of the New Look; his archive is today a treasure trove of enticing images that demonstrate the creativity of Dior’s Haute Couture and the successful commercialization of the house’s perfumes, furs, shoes, and accessories.

Likewise, both men played a primary role in the 20th century’s consecration of designers, interior decorators, architects, fashion designers, hairdressers, stylists, and other purveyors of luxury. André Ostier worked closely with Edmonde Charles-Roux, who became the editor-in-chief of French Vogue in 1954. For several years, André both wrote and illustrated the magazine’s well-known social column, La Vie à Paris. A natural precursor of the post-WWII generation of paparazzi, André became the chronicler of Paris high society. Iconic figures were defined by the eminently elegant photographs he took of the post-war fancy-dress balls and parties in Venice, Paris, Versailles, Biarritz, and other places where the rich and famous would gather.

Christian Dior and André Ostier shared yet another field of parallel interests. In his 1956 autobiography, Dior by Dior, Dior admitted that since he had been a child, he had felt a calling to be an architect. In expectation of his mill at Milly-la-Forêt, near Fontainebleau, and the house, La Colle Noire, he was to buy overlooking Grasse, this inclination took the indirect form of designing fashion. As for Ostier, his fascination for layouts and composition led him to photography before he discovered other more direct architectural interests in the arrangement of his Paris residence, and the defense of Paris’ urban environment. Lastly, Dior and Ostier both appreciated music. They often attended performances of concerts or the opera together. They became friends with several musicians of talent: Georges Auric, Darius Milhaud, Erik Satie, Henri Sauguet et al. Ostier and Dior had also met the American composer Virgil Thomson—a key figure on the Franco-American cultural scene—who had set Gertrude Stein’s play Four Saints in Three Acts to music at the end of the 1920s. In 1940, Thomson composed a musical portrait of André Ostier.

The photograph on page 113 of this book captures the view from across the Seine of the building at 17, Quai Voltaire, in which Thomson had resided since 1927. The composer chose to reproduce that image on the back cover of his autobiography, Virgil Thomson by Virgil Thomson (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1966). Although the photograph represents primarily an urban scene, nature is nonetheless decidedly present. André chose to describe the quiet majesty and constant movement he associated with artistic endeavor by emphasizing the expanse of the Seine in the foreground. Yet the resulting musicality is framed by the late-18th-century constructions across the river, and the proximate solidity of the tree on the Right Bank.

Although other historians and editors shared similar concerns during the same period, Ostier was not interested in drawing up an extensive inventory or register of streets and buildings according to a pre-defined classification. That was the work of such photographer–archeologists as Eugène Atget, who provided “documents for artists;” collectors specializing in the history of photography, such as Yvan Christ; or urban historians like Jacques Hillairet, who used pictures mainly to illustrate and embellish their text.

André Ostier approached others—the primary subject in photography—as he did life itself. Carefully defining the distance from the focal point, he exploited an intermediate space that allowed all phases of existence to occur concomitantly, be they intellectual, emotional, sentimental, physical or spiritual. He admired the precision and technical quality of certain photographs, but felt that the neutrality of the images lessened their impact. He appreciated the emotion that was expressed, although he thought excessive effusiveness could overwhelm meaning. He was fascinated by the creative urge, and sought endlessly to capture the gestures and attitudes that signaled its presence.

Paris is perennial, and to maintain this characteristic, it appears now necessary to ensure that the images presented in this expanded, embryonic volume were published in the 21st century, avant qu’il ne soit trop tard. Splendidly reproduced in Paris from the original negatives, prints or contact sheets, they are a pleasure for the eye and spirit. While these photographs provoke a lingering sense of nostalgia in the face of inevitable metamorphosis, they remain chiseled in our memory as a testimony to the importance of the past and the hope of the future.

Thomas Michael Gunther

Thomas Michael Gunther is a Ph.D. in philosophy, a historian of photography and former senior lecturer at the Institute of Political Studies in Paris. He lives and works in Paris.

André Ostier, Paris avant qu’il ne soit trop tard

Published par Pointed Leaf Press

65€