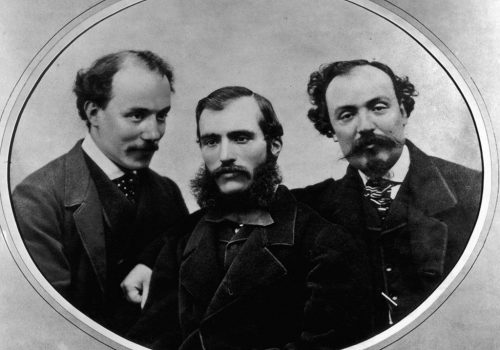

The imagery of Italy and of Italian art is nested in the Alinari archive in Florence, which has trained and informed generations of tourists and art enthusiasts. Its photographic production and the collection of images and archives has been proceeding for 168 years, spanning three centuries, without interruption. The atelier was established in 1852, in the capital of the then Grand Duchy of Tuscany, by the three Alinari brothers, Giuseppe, Romualdo and Leopoldo, who began their activity as photographers some thirteen years after photography was born.

In this weird year 2020, Alinari highlights two different and significant occasions. The first one is the transformation, that took place just over a century ago, in April 1920, when the Fratelli Alinari changed its structure becoming a joint-stock company, with the acronym of I.D.E.A. (Institute of Artistic Editions). The second event is the recent acquisition of Alinari institution by the Tuscany Region, so that this immense archive continues to be a heritage of the city (and of the Country) where it was born.

Let’s ask Paola de Polo, CEO of Alinari, to take us through the history of this unique reality.

In 1854, two years after the atelier was born, the Alinari brothers created a family company, the Fratelli Alinari. In 1861 they also built their headquarters, in Largo Alinari. Their work was successful, as Tuscany and Florence were main destinations for the Grand Tour travellers, to whom they provided images of their “voyage”. Before photography was invented, those who wanted to see the Tower of Pisa, had to go in person to Pisa. After the invention of photography, it was the Leaning Tower that could go around the world.

In other words, photography made it possible to travel around the world without leaving home, which turned out extremely useful even in this spring 2020, in order to keep promoting the culture. What about the quality of the works by Alinari?

The Alinari were enlightened photographers and entrepreneurs. They took care of quality and technological developments of photography as suggested, for instance, by the correspondence with Nadar and the most important French photographers of the time (at its very beginning, photography was considered “a French art”). Just out of curiosity: Alinari’s photographers, who were quite a number, didn’t sign photographs. So, we don’t know who took the images, all of which are signed by Archivi Alinari, precisely because they all had to be of equal quality, of the same precision, of the same beauty. That means all the photographers had to be equally very skilled. The Alinari used to create high quality works, artworks, though openly commercial, as they were produced to be sold to international travellers. In the second half of the 1800s, the Alinari photography had definitely carved out an autonomous place for itself on the cultural scene in Italy and abroad, transforming the business into a real leader actor in the sector. Which brings us to 1920. Vittorio, the last heir of the three Alinari brothers, Giuseppe, Romualdo and Leopoldo, sold the company to a group of shareholders, identified by Vittorio Emanuele III, King of Italy, so that these ninety-two well-known and trusted people would preserve the cultural Italian heritage through images portraying history and society. Thus, the oldest company in the world still active in the field of photography, the Fratelli Alinari IDEA – Institute of Artistic Editions”, was born.

The photographs of the first decades by Alinari often showed Italian squares, streets and even canals (in Venice) near deserted, in full documentary style, so unthinkable until a month ago. The same is true for images such as St. Peter’s square crowded with people and carriages (1869), if compared with those shot in recent times.

In the 1800s, images had better not to include people (or animals!), because of the shutter speed and in order to avoid the so-called ghosting effects, that is the shadow effect of those moving during the shooting. Furthermore, the photographers’ favorite places were less crowded than they used to be in the last decades. Returning to the subject, in 1940, Senator Giorgio Cini became the company owner. Besides the existing Alinari archive (some 120,000 negatives on a glass plates), various competing archives were purchased, including Brogi, Anderson or Chauffourier. In doing so, he managed to concentrate in one place most of the history and visual culture of Italy. All these archives had a territorial specificity, being born in the pre-unitary period. The Alinari, for instance, began their own activity in the then Grand Duchy of Tuscany. In 1985, Alinari decided to go beyond its traditional activity, creating the Photography History Museum and the Library with some 20,000 volumes. Meanwhile a huge photographic collection was going to be created, by acquiring photographs from all over the world, dealing with all subjects and all photographic techniques, from daguerreotypes, though the Alinari never used them, to digital images, from the construction of the Chinese railways to the Native American history. Nowadays Alinari owns over five million photographs (both vintage prints and negatives), including the photo campaigns the company went on to shoot over time. This precious heritage has been transferred to the Tuscany Region in December 2019 – an excellent solution, I think – and we all are waiting for the most appropriate conservation and exhibition venue to be identified (at present probably Villa Fabbricotti, in Florence). The move was an epic but rewarding adventure from a cultural point of view. Indeed, while the materials were moved from their original storage place, we found handwritten notes with interesting indications on the original parcel paper the Alinari used to wrap glass plates.

In your opinion, which are the most significant photographs in the Alinari’s iconographic heritage?

According to the Grand Tour travelers’ whishes, the Alinari produced the most classic views of monuments and landscapes. They also created major photographic campaigns such as the one on the Uffizi Gallery. At that time, it was the only way to let the Italian art be known around the world. It is worth mentioning other archives which are part of Alinari I.D.E.A., such the Wilhelm von Gloeden’s one. Or the Wulz’s archive, that gathers works by three generations of photographers active in Trieste in the early 1900s. By the way, Wanda Wulz joined the Futurist movement and her photos were often created by using superimposed images as in “Io+gatto”, her self-portrait merged with a portrait of a cat, an icon of world photography. We also conserve some albums by Felice Beato, with gorgeus hand-colored photographs, obtained thanks to the refined skills of Japanese watercolourists, and the Villaniì’s archive. The Studio, among the best known specialized in industrial photography, was active between the 1920s and the 1990s allowing us to reconstruct the history of the Made in Italy, from Ferrari to Ginori”.

Paola Sammartano

Paola Sammartano is a journalist, specialized in arts and photography, based in Milan.

Fratelli Alinari I.D.E.A. spa

Largo Alinari 15

50123 Firenze, Italy

www.alinari.it