A Galerie, in Brussels, Belgium, exhibits acclaimed Magnum photographer Alex Webb.

Wherever he goes, from Istanbul to Amazonia, from Mexico to Haiti, Alex Webb takes the pulse of the world in the streets, not as a thief stealing lives, but as an ambassador of the gaze of peoples, in which he reads their joys as well as their suffering and their tragedies. The pulse beats to a nearly tachycardiac rhythm, where one moment splits into several, a fraction of one person’s existence mingles with another’s, then another, until one isn’t sure which scene to admire first. There is a forcefulness in the artist’s ability to represent human complexity in a vision of equal sophistication. His images are like a patchwork of colorful stories, where men look back at him and at each other, work, resist, play, think, win, wonder, laugh, feel. He plays hide-and-seek with his fellow humans for whom he reserves a special skill: his unparalleled ability to manipulate light and shadow so as to conceal some things and reveal others, only to better look into the viewer’s soul and examine their conscience. His bearing contrasts with the flurry of activity in his photographs: Alex Webb is discreet, has gentle eyes, and the beard of a writer who has been working in seclusion for weeks—telltale signs of that poetry of the everyday he has nurtured since he was six and received his first image box, a Kodak Brownie: a camera, not a cookie.

In Ostia Antica, in Italy, there are remnants of an ancient roman harbor and a humble grove of umbrella pines. Visiting it as a child while on a trip to Europe, Alex Webb collected a pinecone. He brought the fruit to his parents and a friend of theirs, Giorgio Bassani, the author of The Garden of the Finzi-Continis. “It was much larger than those I was familiar with in Connecticut,” he recalled. “I excitedly ran up to my parents to display my find. Bassani reached down, grabbed the pinecone and held it high over his head, about to hurl it to the ground, saying: ‘You see, in Italy we break them like this to get the pine nuts.’ I burst into tears and Bassani—perhaps a little mortified at the little American child’s distress—kindly handed me back my pinecone. I carried it with me for our entire two-and-a-half months in Europe and brought it back to the U.S.”

Born in San Francisco in 1952 to parents who were working in literature, drawing, and sculpture, Alex Webb was raised on the east coast of the United States, between New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. Creativity was a part of his daily life, exerting a pull on the child to imitate his parents and familiarize himself with visual arts. “From an early age I drew, painted, and sometimes made sculptures,” he said. “I was fortunate to have incredibly supportive parents, both deeply immersed in the arts, who encouraged most of the creative efforts of their children. My father was a publisher, editor, secretive fiction writer, and occasional photographer; my mother was a draftsman and sculptor; my brother is a painter and teaches at Pratt; and my sister, who briefly tried to escape into the sciences, ended up an ornithological illustrator and children’s book author. When we were children, art was everywhere: in my mother’s studio, in the museums that we visited frequently, in my father’s immense collection of books, including a fine photographic library.”

For the past thirty years, Alex Webb has shared his life with his wife Rebecca, who is also a talented photographer, and thus a privileged partner in his photographic wanderings. Together, they inhabit the parlor floor of a nineteenth-century brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn. It’s a beautiful home he feels lucky to be able to rent, given the sky-high cost of living in New York. Their living room is literally bursting with photographic prints, book layouts, works in literature or photography, novels and books of poetry. The walls are covered with the couple’s own and their friends’ images, paintings, drawings, and an exceptional collection of masks—from Mexico, Puerto Rico, Vanuatu—which Alex Webb had collected over the years simply because “he always found them intriguing.”

When Rebecca and Alex Webb are tired of New York and its relentless bustle, they take refuge in Wellfleet, a small coastal town on Cape Cod, whose name derives from “whale fleet.” Alex’s parents bought a summer home there in the 1960s, a peaceful residence where they could enjoy the marine climate, with its sea breeze and sunshine, gusting winds and tides. “Wellfleet in the early 1960s seemed to be a haven for many New York intellectuals, many of whom were friends of my family,” he explains. “I remember that every summer our family would to go Katie Kazin’s [daughter of the noted cultural and literary critic Alfred Kazin] birthday party. There was always a fellow there who did magic tricks. It was Edmund Wilson, one of the most prominent historians and critics in the country at that time…. Wellfleet is where my wife and creative partner, the photographer Rebecca Norris Webb, and I try to go as much as we can to edit our photographs, to write, and to lay out books. I feel that the quality of some of my recent books—as well as Rebecca’s and my recent collaborative books—is directly linked to our being able to work on them on Cape Cod. The place is a kind of creative sanctuary for both of us.”

Painting and photography

Despite the frenetic activity they may portray, their copious detail, and their frequently political nature, Alex Webb’s images have the ability to soothe those who look at them. This is due in part to his tremendous sense of composition where different planes overlap, correspond, or dialog. Sometimes, this singularity comes across in subtle abstraction—an apparent mystery or missing information, which go against the grain of documentary photography. His language is akin to painting, at which he actually tried his hand before turning to photography. Among painters, he is particularly fond of Giorgio de Chirico and Georges Braque: the former, for his surrealism, his dream-writing, and his metaphysical oeuvre; the latter, for his chromatic boldness and innovation.

“I suspect early on their visions, their artistic transformations of the world, affected how I see,” he explained. “I clearly have an aestheticized vision. This is not something that has evolved intentionally or rationally. It is part of what I feel and how I see. Presumably my childhood, my education, and perhaps even my genetic makeup play a role in this. I’ve always been intrigued by somewhat complicated images. I’m interested not just in the one object or person in front of me but in how multiple elements can co-exist and qualify one another. I suspect it ultimately comes out of my sense of the inexplicable complexity of the world. When I am actually photographing on the street I think that I am both highly attuned to the world and at the same time almost daydreaming. My mind floats while my eyes and other senses remain alert.”

Several times in his life, in moments of self-doubt, the American photographer thought of dedicating himself to writing fictional stories, “under the influence of his father.” Literature as a form of escapism: not unlike the motivation of certain journeys and creative projects. Among his inspirations were the English writer Graham Greene, whose books were Alex Webb’s primer to Haiti and to the American-Mexican border region, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Mario Vargas Llosa, whose magical depictions of reality were his doorway to Latin America. “Other important influences include Cartier-Bresson’s The Decisive Moment and Frank’s The Americans. I also was intrigued early on by some of Friedlander’s complex social landscape images and Metzker’s dark moody urban scenes. And finally, the music that I have always felt complements my work and that I listen to most is the blues, including Albert King and Buddy Guy when he played with Junior Wells.”

His kinship with dreamers, his taste for the new, perhaps even the unfathomable, have nourished Alex Webb from the start. These qualities translate into practice in the streets, where he roams and explores, guided by his eye and his camera to get a glimpse of whatever he might discover. He believes in spontaneity and in the intuitive process which pulls him toward the unexpected. Open-minded, he awaits intrigue, attracted by places rife with paradox, cultural conflict, enigma, and urban confusion. His role is to ask questions rather than to offer answers. But Alex Webb always asks his questions in raw and vivid color, as if to show the way towards a positive outcome and a better understanding among people, towards cultivating difference, and maybe even ending social injustice and bringing peace. More than anything else, this is a documentary photographer’s dream.

One place, one book

Alex Webb, who is a regular contributor to major publications such as the New York Times Magazine, Time Magazine, and Géo, has published eleven books to date, including Hot Light / Half-Made Worlds; Under a Grudging Sun; Dislocations; Crossings; Istanbul; and The Suffering of Light. His latest, seemingly unimposing release is entitled La Calle: Photographs from Mexico, and was published by Aperture in the fall of 2016. It brings together a selection of photographs taken over the course of forty trips to Mexico between 1975—the year when Alex Webb joined the prestigious Magnum agency—and 2007. It offers a magnificent document of this—at once complex, volatile, and sublime—country which the photographer loves with a visceral passion. The images, some of which are widely known, evince Alex Webb’s distinctive style: animated scenes, extraordinary even in the treatment of ordinary subjects, skillfully juxtaposed in playful composition, crisscrossed by shadows, and containing recurring elements, such as people hugging or cotton candy—all rendered with great tenderness. To cite some of the most recognizable pictures: Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, 1996; León, Guanajuato, 1987; Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, 1985; Boquillas del Carmen, Coahuila, 1979.

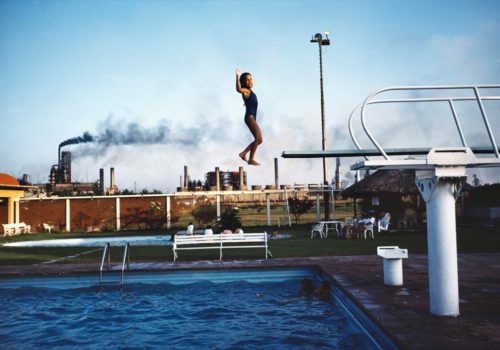

The inventory of Alex Webb’s works contains one common denominator: every book is dedicated to one country or one location; and there are no traditional journalistic subjects—a fact he explains by sheer instinct and the images’ relationship to his own life. “My choices of where to go to photograph have been unplanned and may seem—at least initially—a bit incoherent. I sometimes liken my process of choosing projects to the process of decisions in life: something happens, one responds. As I said before, my initial trips to Haiti and the U.S.–Mexico border were prompted in part by reading Graham Greene’s The Comedians and The Lawless Roads. Those trips were also motivated by my increasing struggles with my photography in the U.S. I felt that my pictures from the American social landscape were increasingly stale: ironic perhaps, but not resonant. I needed to find something else. I ultimately discovered that something else in the so-called tropics: a way of seeing and responding to the energy and the rawness of life as lived on the stoop and in the street. Soon thereafter, responding to the intense light and vibrant color in these places I discovered working with color film. This way of seeing in color is probably my most significant insight as a photographer. My Florida work emerged out of the time I spent in Miami waiting for disturbances in Haiti to subside: I began to look at the strange and complicated state of Florida—new immigrants, but also leisure Florida. Working in Cuba was a natural outgrowth of earlier Caribbean work. Ever since I first went to the U.S.–Mexico border I’ve been intrigued by borders. Istanbul—a later project—is another kind of border: ancient and modern, Islamic and secular. And in some recent work in the United States I am beginning to explore borders within the United States: the feel of different ethnic—often contiguous—neighborhoods in Brooklyn, for example.”

Although Alex Webb did, on occasion, capture reality in black and white, as in his early work or in Memory City (2012)—a series on the town of Rochester, NY, created jointly with Rebecca—color film has always been his medium of choice; more specifically, the inimitable Kodachrome, which the artist has been using for thirty years. Alex Webb’s collaboration with his wife has never been closer: they are in the process of completing their next book project, forthcoming in 2017 and entitled Slant Rhymes—a series of photographs illustrating the relationship between their photos published on Instagram and their penchant for surreal, surprising moments. “I am working on a couple other new projects,” he added. “One is a collaborative book with Rebecca on Brooklyn. I’ve been wandering the streets of this borough over the last couple years, passing through a multitude of cultures. It’s almost as if I am following the path of some thirty years of photographing all over the world, but instead of traveling by plane I travel by subway. Rebecca, meanwhile, has been photographing our immediate neighborhood in and around Prospect Park and the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens. We envision a book entitled The City Within, as Brooklyn used to be its own city at the turn of last century, and Rebecca is photographing the city within the city, our neighborhood which lies in the heart of the borough. Every project is like a journey, but until I’ve completed it, I never know where the journey will end.”

Anyone who knows Alex Webb has an image of his tucked away in memory. Or even several images. There is one’s favorite, one’s second favorite, and so on. They vie for attention in classrooms and newsrooms. Everyone has their own opinion: as if they were present at the moment that the image was taken; as if, by force of projection, they were part of the scene, in some distant corner of the world. The images lend themselves to a treasure hunt. Once Alex Webb even said, “To a certain extent, what I do is play with the world, but it’s disciplined play.” It’s worthwhile play that involves traversing the globe and telling the stories of human trials and tribulations; making things clear, questioning, and giving hope. When Alex Webb is not traveling, observing other people, or working, he is secluded on Cape Cod reading crime and mystery novels, or laughing while watching Trevor Noah, the new host of the satirical Daily Show, because “humor is key to survival.” He is moved: by the events in Syria, the Middle East in general, the land of interminable conflict. And above all, he is filled with indignation. “I am currently distressed that so many citizens of the United States can support a narcissistic demagogue like Donald Trump.”

Jonas Cuénin

Alex Webb

March 17 to May 20, 2017

A. Galerie

25 rue du Page

1050 Bruxelles

Belgium