Synonymous with the art of traveling since 1854, Louis Vuitton continues to add titles to its Fashion Eye collection. Each book evokes a city, a region or a country, seen through the eyes of a fashion photographer.

This fall, Louis Vuitton Editions publish two new jewels. The first of them, Japan, of the baron and man of worldliness Adolphe de Meyer, opens an unrecognized chapter of his photographic work. Discovered during a trip with his wife Olga Caracciolo, this series shapes a romantic representation of Japan: a fantasy country, perpetuated in its landscapes, traditions and bucolic scenes.

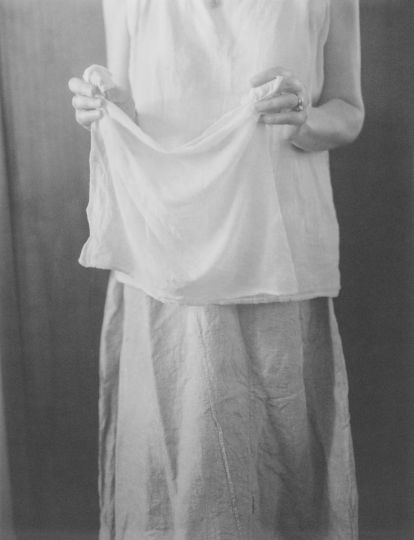

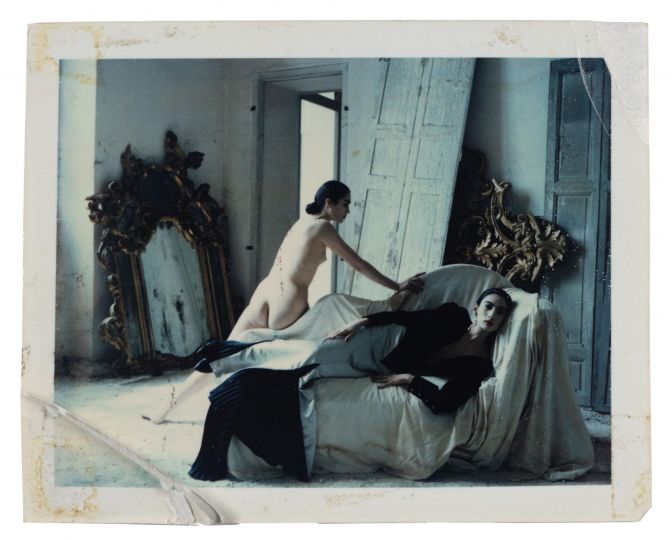

The photographs of Japan by Adolphe de Meyer have long been unknown. The Baron kept them until his death. The Sotheby’s house unveiled this set at the sale of his collection, October 20, 1980. Voluntarily and partially destroyed during his life, his work remains famous for his fashion photography, taken in the studio, where his models – countesses, aristocrats and artists – To the toilets raised and thin pose front, lascivious, in stagings playing an imaginary symbolist accents. Preserved largely at the Metropolitan Museum (New York), the Japanese series is still foreign to us. She is this tiny part of her work, drowned in a larger set of travel memories (Venice, Turkey, Greece …).

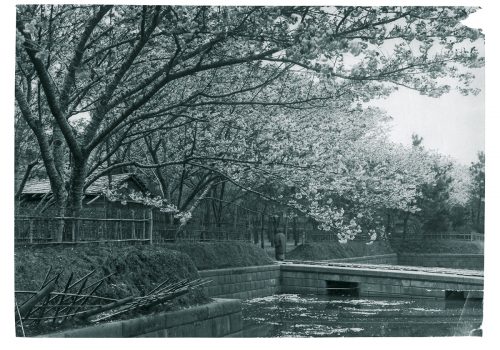

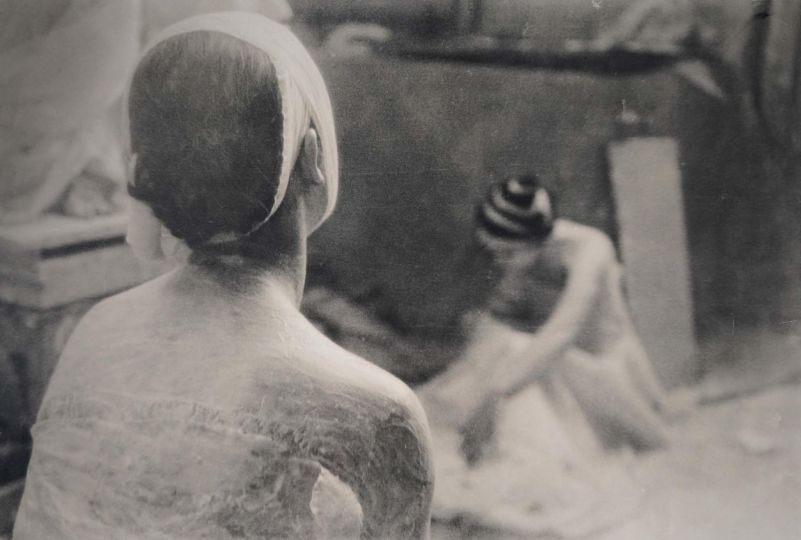

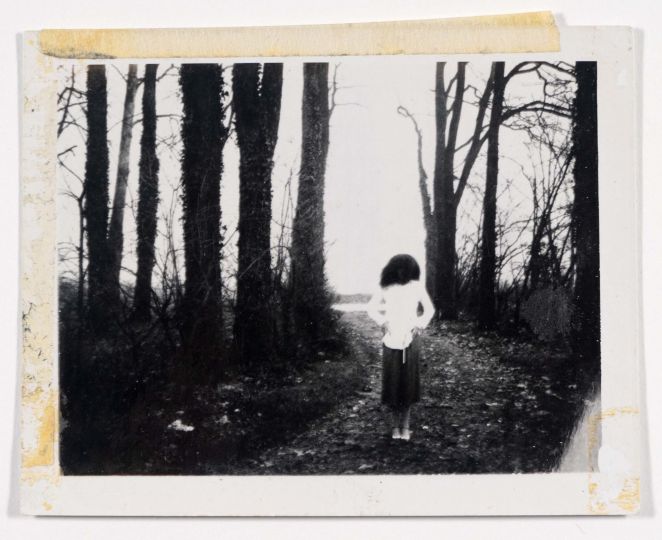

With the exception of his wife, human presence remains rare in this series. The photographs reveal mostly depopulated landscapes and show Baron’s tourist fascinations: the Nunobiki Falls, the cities of Kamakura, Kyoto and Nara, the temples of Kinkaju-ki and Kiyomizu-dera. The strolling of the baron goes from gardens to parks, from forests to grandiloquent temples; the stringy coasts prolong the silence of the landscapes. Arches, cherry blossoms, water lilies and bridges come to close a painting quickly perceived nowadays as folkloric, and which however resists the mockery or the disdain by the beauty of the landscapes and by its general vision.

The curiosity of the Baron for Japan seems sincere, his journey traced on a map attests to his will: seize the vastness of the country. Fascinated, De Meyer records all the symbols of his traditions of his religious culture. He is one of those enlightened travelers, the trip to Japan remaining early nineteenth century the prerogative of a certain economic and cultural wealth. Considering his passionate life, fully worldly, shared between several continents, this trip may seem a posteriori to be a personal retreat; his aesthetic fascinations ranging from his wife – friend and confidante – to the architectural brilliance of a traditional Japan. His photograph is filled with symbols of Japanese culture, but rather with playing music with the symbolic, such as his series Prelude to the afternoon of a fauna; rather than curling with the dream, the fantastic or the hallucination, it reveals the simple “state of things”.

This Japan does not live, it is based on a perception “out of time” (Camille Mona Paysant). The city is never shown, even though Kyoto was at the beginning of the twentieth century as an urbanized city, still little perverted by mercantile trade, but simply vivacious as teeming. Japanese society is deliberately put aside, except in its architectural achievements, in its ceremonies and religious fact. The photographs boil down to a succession of walks, punctuated by still shots. A roaming of the peaceful. This vision is not necessarily Western. Here, no lawsuit against a supposed Orientalism, but rather the will to underline how much the legitimate fascination of the artists of the end of the XIXe century for the wealth of Japan gave birth to a common aesthetic.

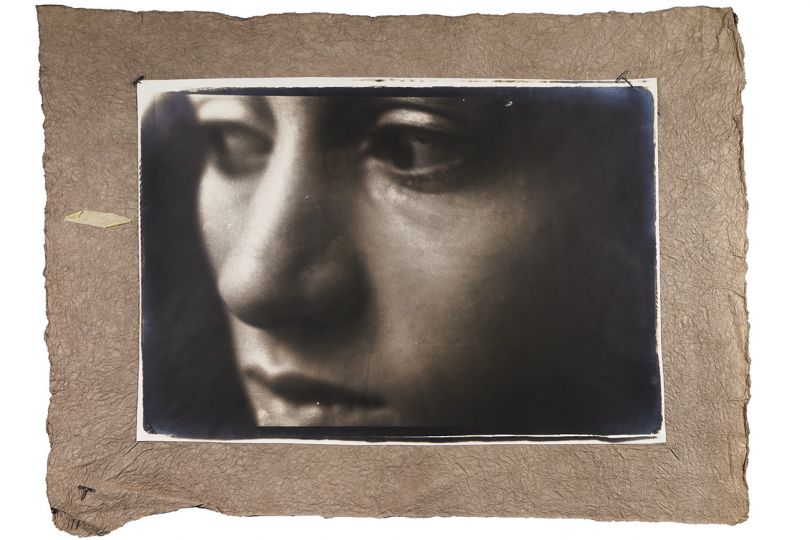

This standard aesthetic draws a country frozen in its rurality, in memorial landscapes. This Japan is perpetuated in a “fleece and vaporous atmosphere”, words of the excellent essay by Camille Mona Paysant at the end of the book. If Meyer’s photographs were not known at the time, remaining in the circle of intimacy, they fed on the vision of an eternal land, initiated by the commercial distribution of Japanese prints in the nineteenth century, magnified by the travelogues in Japan (Ernest Mason Satow, Henry T Finck, Herman Hess) and completed by the world exhibitions.

Fine connoisseur of the work of the Baron, Camille Mona Paysant shows how much this aesthetics of eternal Japan was in phase with the Japanese photography studios of that time, such as that of Kusakabe Kimbei (certainly more centered on the human figure). This aesthetic finally forges a Japanese-style romanticism, shared as much by the Japanese seeking to sublimate their country by its nature and its culture as by Western artists, praising the new brilliance of an unknown culture. De Meyer feeds this fascination. Thus the words of Henry T. Finck can resonate with the Baron’s images: “What they can offer us is, on the whole, of a greater and noble order than what we can offer them”.(1)

Japan Editions Vuitton plays skilfully with the fascination of the Baron. The book restores the vision as much as the technical gropings of the Baron, helping to forge his style. He used processes already used (coal prints, albumen paper). The book underlines the unknown taste of De Meyer for a love photograph, probably unconscious, and today seems very slightly stereotyped. This photographer draws a hollow Japan; the land of silence. This one still participates of a collective aesthetic vision, constructing image by image, the imaginary of a myth.

Arthur Dayras

(1)Henry T. Finck, « what they can offer us is, on the whole, of a higher and nobler order than what we can offer them », in: Lotus-Time in Japan, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1895, p. 332-33