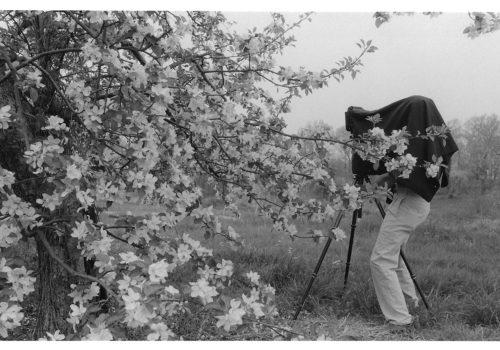

In early 1978, I went on a journey to the Lower Rhine with Joseph Beuys and art historian Peter Sager. Our travels led us back to Beuys’ origins, back to his roots near the city of Kleve, where everything started – his life and his legend.

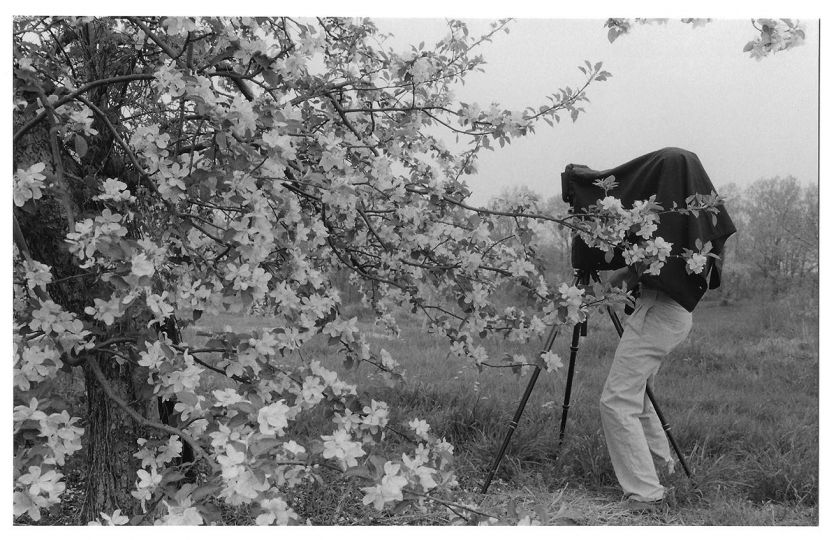

Before his 1979 retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, we wanted to capture the artist as he reconnected with his past. To Beuys, it was a gaze back into a landscape with a low horizon and high skies. Simple and sparse, barren like his works – foggy fields occupied by osiers, poplar trees, and basket willows. “These oddballs who master the bizarre art of brooding as virtuously as Joseph Beuys. A landscape in green and grey, felt-grey,” said Peter Sager.

Many of the photographs I had taken of Beuys were journalistic in character. This time, I wanted one symbolic image depicting it all in a single frame: the artist, the references to his art, the landscape, and his origins. In his words, we were creating “a sculpture” since “the formation of a thought is already sculpture.”

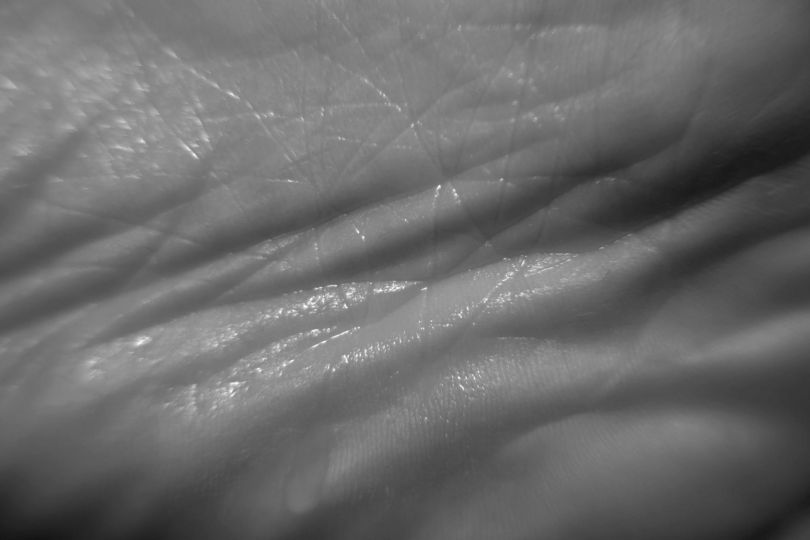

Although it was not an easy task, luck was on our side. We learned that Leni van Heukelum, a local farmer turned art collector, had snatched up Joseph Beuys’ crib. We – Beuys, Sager and I – decided to buy a dead hare at a butcher’s shop. The hare had always played a major role in his art. How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare was one of his best-known performance pieces enacted in 1965 at the Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf. “The hare is my animal,” said Beuys, “extremely prolific and mobile, a zigzag runner and border crosser, at home right across the steppes, buries itself in the earth, has a dark character, a completely different blood chemistry from other animals.”

But then came a catch. We were stunned to discover that it was a Biedermeier crib, and Beuys became reluctant. The fact that baby Beuys once lay in this bourgeois furniture did not appeal to him at all. But we found a solution: In the photograph, he does not stand next to it or even touch it, (as originally planned) but instead in an imploring, Shaman-like pose, holds the hare between the cradle and him making sure to keep his distance from the unfitting past – a disconnect that adds mystery to the scene.

Some of the photos I produced during our journey were published in the German Zeit-Magazin in 1978, accompanied by an essay by Peter Sager, Beuys: Die heilige Kuh vom Niederrhein (The Holy Cow of the Lower Rhine). However, much of the work remained unseen by the public until 2012, when a collection of large prints was acquired by the museum in Kleve.

Gerd Ludwig

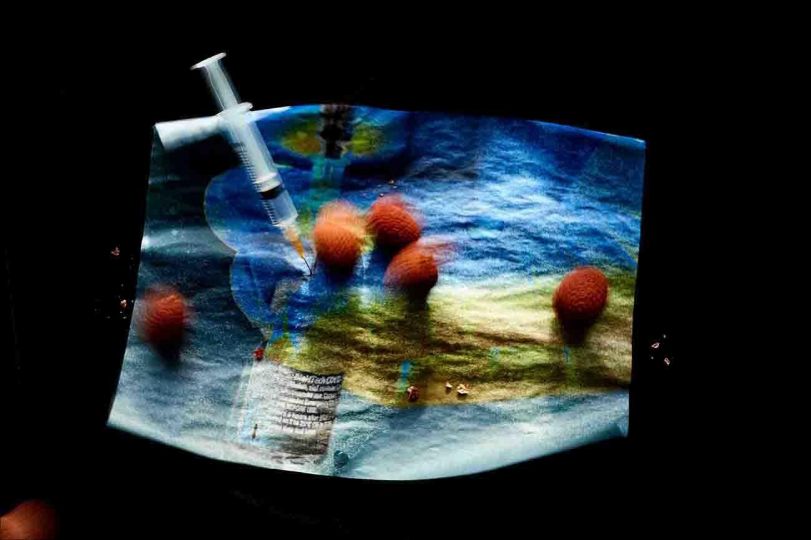

Gerd Ludwig is a photojournalist, working for National Geographic since 1980. His recent publication, The Long Shadow of Chernobyl (2014), documents the 20-year aftermath of the Chernobyl accident. Ludwig’s work focuses on environmental issues and socio-economic changes in Russia and throughout the world.