Much ink has been spilled over photography, from the moment its invention was announced in 1839 through the latest developments in digital techniques. Until now, a history of this critical activity had yet to be written, and a question needed to be raised: what differentiates photography criticism from art criticism? From Charles Baudelaire to Roland Barthes, to Walter Benjamin and Susan Sontag, to Hervé Guibert and Georges Didi-Huberman, this book offers a survey of the multifold debates and discussions provoked by this mode of expression and representation which continues to evolve and question reality.

“All arts live by words. Each work of art demands to be answered, and the written or unwritten, immediate or meditated ‘literature’ is inseparable from what drives man to create.” – Paul Valéry[1]

The objective of this book is to identify, in the history of the medium, from its origins through the modern and contemporary periods, the specificity of photography criticism. This task is made difficult by the proliferation of writings about images as well as by the multiplicity of the disciplines and fields of knowledge represented by the authors. Their background may be in philosophy as much as in any of the various disciplines in the humanities and social sciences, including sociology, anthropology, psychoanalysis, as well as semiology and structuralism. Let’s recall, with Anna Siegel in her Observatoire de l’art contemporain (2015), the general definition of criticism: “The word ‘critic’ derives from two Greek words: kritikos (discernment) and kriterion (the norm). Thus the word ‘criticism’ implies ‘an acuity in norm-based judgments’. This etymological definition raises the following question: what norms are these? The critic is someone whose own norms challenge the existing norms. Consequently, he or she gives an account of that difference.” The history of photography, by setting itself off from painting and sculpture, has gradually established its own norms. These norms have also been defined through the materials and formats.

While critical practice may be easily assimilated to the journal or magazine format, in modernity, most critics devoted themselves to the book, while others coupled that activity with curating exhibitions.

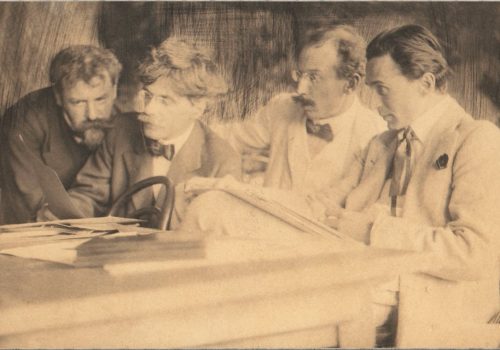

We may thus associate the first specialized critics, such as Ernest Lacan and Waldemar George, with the journal La Lumière; and when, in 1982, the Éditions Créatis, founded by the eponymous gallery, published the book Anthologie de la Critique: 15 Critiques 15 Photographes, they are all contributors to daily newspapers or general-interest periodicals such as Le Nouvel Observateur, art journals (Art Press), or work for the radio (France Culture). We should not, however, as Walter Benjamin pointed out, confuse a journalist with a critic: “the commentator can stand before [the work] like a chemist, the critic like an alchemist.”[2]

French criticism has often been more literary than Anglo-Saxon criticism which is linked with the visual arts. Thus, Paul Valéry’s famous “Discours du centenaire” (Centenary Lecture, 1939) insists on the rivalry between visual arts and textual arts and shows that photography undermines literature’s descriptive project. Its true revolution consists in radically changing our way of seeing the world: “Thus the very existence of Photography might discourage us from making further efforts to describe what can be automatically inscribed.”[3] In his Preface to his Critical Essays (1964), Roland Barthes insists in turn on the literary character of criticism: “the critic is the person who is going to write and who, like the Proustian narrator, satisfies this expectation with supplementary work, who creates himself by seeking himself and whose function is to accomplish his project of writing even while eluding it.”[4] Georges Didi-Huberman modernizes this formula: “Seeing rhymes with knowing, which suggests that there is no such thing as a savage eye, and that we also grasp images with words, with procedures of knowledge, with categories of thought.”[5]

These literary proponents and specialists work next to artists who, in their writings, have from the very beginning pursued valuable lines of critical reflection. Further, we should not separate specific criticism from art criticism, since many writers have ventured into both domains simultaneously. While art criticism has its origins in engraving, which made the reproduction of paintings possible, the early 19th-century texts, by contrast, were unable, for technical reasons, to include photographic reproductions, which forced them to develop a descriptive method. This was first introduced in La Lumière, a journal founded in 1851. Similarly, for the sake of editorial economy and costs, when Hervé Guibert took over the critical column in Le Monde in 1977, he wrote for readers who may never see the image either exhibited or published. For this reason, Robert Pujade defined his aesthetics as “A letter to the blind”: “[Guibert’s] articles may as a whole be considered to be letters to the blind, to a public deprived of illustrations, for whom he was obliged to trace back the journey of his personal writing: transform the photographs he had before him into fantasies, into the desire of seeing.”[6]

The essential difference between photography criticism and art criticism lies in the fact that, as Michel Frizot put it, in the former, the image is itself the instrument and the medium: “In the history of photography we are thus faced with the strange situation of, on a daily basis, studying in an artistic domain the very medium that also serves us as the medium for analyzing art and its history.”

However, we can discern attitudes different from those encountered in general criticism: historical scope, descriptive or formal approach, deeper engagement resulting from academic or ideological attacks, and subjective criticism that rises to the level of the work of art.

Certain recurring themes appear throughout the history of the medium. The question of retouching, for example, was raised as soon as the negative-positive photographic process was invented in 1840, and it gained momentum with the shift from paper negatives to glass negatives in 1850 (namely thanks to the technique of wet collodion). In 1902, the debate pitched Robert Demachy, a French enthusiast of retouching, against the Englishman Frederick H. Evans, an advocate of straight photography free of artistic intervention. In 1914, Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand rejected pictorial photography. Similarly, in 1935, the group F/64, founded on the West Coast of the United States, challenged the theses proposed by William Mortensen, who had formed a school of his own in Laguna Beach in 1931, aiming to renew pictorialism. The quarrel was revived in the late 1990s with the advent of digital photography.

One of the biggest debates in photography criticism was centered on the question whether photography was an art form: “In the first issue of the magazine Le Photographe, in 1910, we already encounter inquiries into ‘The crisis of photography’ by Albert Londe, ‘On the ownership of photographic images and the right of reproduction’ written anonymously by ‘Un cabochard’ [‘A stubborn mule’], and above all several articles raising questions around the recurrent theme, ‘Is photography an art form?’ by writers such as the Lumière Brothers, Nadar and Victor Hugo, Mendel, Dillaye and Commandant [Constant] Puyo… to name only those in the first quarter of the century.” — Bernard Perrine (Lettre de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts, 2012).

In an effort to integrate photography into the arts, a number of practices emerged seeking the singular quality of production. To counter technical reproducibility and, according to Walter Benjamin, the resulting decay of aura, the number of prints was limited to about twenty in modern times and then to a set of three to five in the case of artists in the second half of the 20th century, who were often working in large format. In the United States, in the 1990s, artists went so far as to destroy the negatives before a sworn witness in order to ensure the existence of a unique print.

By contrast, the value of amateur, or vernacular, production was recognized thanks to the publication in 1982 of Chefs-d’oeuvre des photographies anonymes au XIXe siècle [Masterworks of Anonymous Photography in the 19th Century] by Pierre de Fenoÿl. Other critics, such as Michel Frizot and Clément Chéroux, followed in his footsteps. In his 2006 book, L’Image sans qualité: Les beaux-arts et la critique à l’épreuve de la photographie 1839–1959 [Image Without Qualities: Fine Arts and Criticism Put to the Test by Photography], Paul-Louis Roubert challenged in this context the photographic model proposed in art criticism. In his photography album, Every Photograph is an Enigma (2014), Michel Frizot treats vernacular photographs as a “collection of glances,” and explores “Unusual configurations,” “The enigma of attention,” and “The enigma of relation” engendered by this type of image.

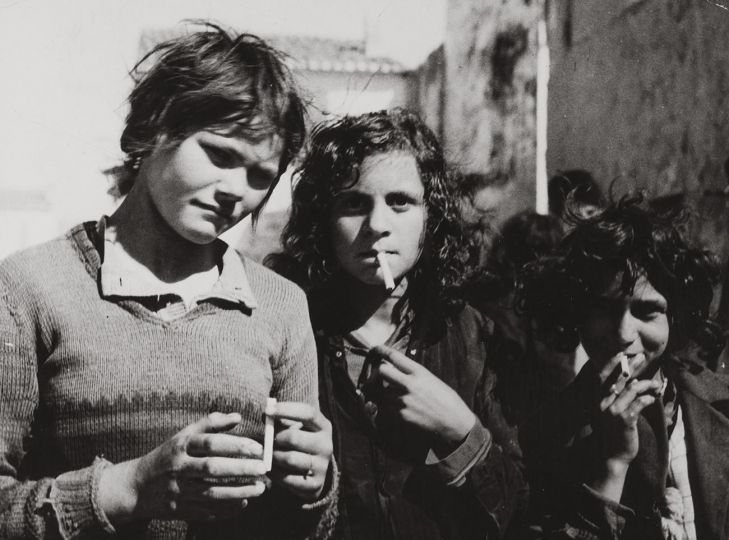

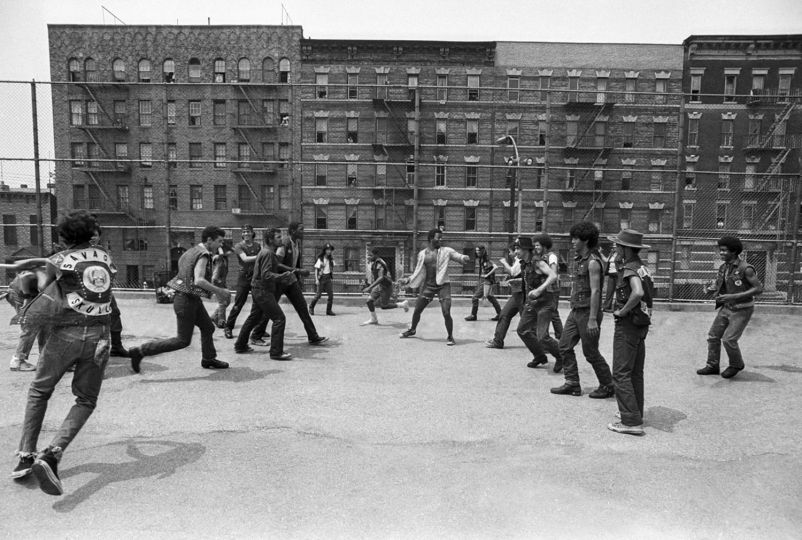

The debate around the issue of the relationship of photography to art was renewed with the importance, from the early days of the medium and at each stage of its development, of documentary practices — a phenomenon thoroughly analyzed by Olivier Lugon in his Le Style documentaire. D’August Sander à Walker Evans, 1920–1945 (2011). Very active in the 1930s, the main participants of the Farm Security Administration’s project offered practical evidence and helped define documentary photography. To the definition offered by Dorothea Lange 1940 — “Documentary photography … is preeminently suited to build a record of change”[7] — one may prefer the one given by Walker Evans in 1971, which has the advantage of opening new doors: “The term should be documentary style. An example of a literal document would be a police photograph of a murder scene. You see, a document has use, whereas art is really useless. Therefore art is never a document, though it certainly can adopt that style.”[8]

The strict categories, specific to given practices, have evolved, and a recent trend saw, for example, creators with a background in reporting carrying out their actions in their field, either by involving the models they encountered in a negotiated photograph, or by working in post-production, both practices resulting in documentary fiction.

The false dilemma of photography belonging, or not, to the arts, is resolved by Walter Benjamin in his “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility” (1935): “… [commentators had earlier expended much fruitless ingenuity on] the question of whether photography was an art — without asking the more fundamental question of whether the invention of photography had not transformed the entire character of art…”[9] Photography had moved from the role of a simple servant of the arts assigned to it by Baudelaire, to being a paradigm. It had short-circuited the ancestral regime of representation, also to the benefit of other arts. We have moved from the regime of the icon to that of the index. In the modern age, photography has been able to inform body art, land art, installations, and happenings. These new connections that photography is developing with action now enable us to speak, on the model established in linguistics and in the extension of that heritage, of the performative image.

The performative image contrasts today with images produced by any recent machine process or software, which excessively insist on a unique mode of capture. As a result of the democratization of the computer, tablets, and smartphones, image production and its transformation are increasingly practiced in a democratic fashion. The dissemination of this type of production takes place faster and faster and reaches ever-wider audiences through websites such as Instagram and Flickr. This abundant production, considered less and less at an individual level, and increasingly trivialized, demands that it be both distanced and better supported by a specific culture.

For at least two decades, the crisis of the traditional printed media, despite the fact that their role has been taken over by the vitality of the Internet, has blunted the impact of art criticism in general, which must now identify new strategies. Giorgio Agamben made this observation already in 2008 in “Qu’est-ce que l’art contemporain?”: “But isn’t the permanent state of crisis to which art criticism is consigned the best proof of its vitality? Compelled to regularly revise their criteria of judgment, and seeking to renew their methods, critics are the first to face the task of rethinking the terms of contemporary creation and to experience its paradoxes in the age of globalization.”

Christian Gattinoni

Christian Gattinoni has taught at the École National Supérieure de la Photographie in Arles since 1989. A practitioner of writing and photography since the mid-1970s, he has carried out a cycle of images on the memory of the history of the 20th-century through an homage to his father as belonging to the second generation. He splits his time between art criticism, exhibition curating, and image pedagogy.

Yannick Vigouroux

Yannick Vigouroux is a graduate of the National School of Photography in Arles. He is an art critic, curator and photographer. In the same collection he published, with Christian Gattinoni, Contemporary Photography (2009), Early Photography (2012) and Modern Photography (2013).

Histoire de la critique photographique

Published by Éditions Scala

€15.50

[1] The excerpt comes from Paul Valéry’s essay “Autour de Corot” in Pièces sur l’art, not from the Centenary Lecture. The readers may access the full text of the 1934 French essay here: http://bergerault-univ-tours.fr/bergerault2001/documents/DOC64.htm. The 1939 lecture on photography, available in French at http://journals.openedition.org/etudesphotographiques/265, is anthologized as “The Centenary of Photography” in Classic Essays on Photography, ed. Alan Trachtenberg (New Haven, CT: Leete’s Island Books), p. 191. — Translator’s note.

[2] Walter Benjamin, “Goethe’s Elective Affinities,” trans. Stanley Corngold, in Selected Writings. Volume 1: 1913–1926, ed. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 2002), p. 298. — Translator’s note.

[3] Valéry, “The Centenary of Photography,” op. cit., p. 192, translation amended. — Translator’s note.

[4] Roland Barthes, Preface to Critical Essays (1964), trans. Richard Howard (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press), p. xxi, translation amended. — Translator’s note.

[5] Georges Didi-Huberman, Devant l’image (Paris: Minuit, 1990), back-cover description (only). This abstract is not included in the English edition. — Translator’s note.

[6] Robert Pujade, “Une letter aux aveugles: la critique photographique d’Hervé Guibert,” in @nalyses: Revue de critique et théorie littéraire vol. 7, no. 2 (2012), https://uottawa.scholarsportal.info/ojs/index.php/revue-analyses/article/view/360. — Translator’s note.

[7] Dorothea Lange, “Documentary Photography,” in A Pageant of Photography 1940. Exhibition catalog, ed. Anselm Adams (San Francisco: S.F. Bay Exposition Co., 1940). — Translator’s note.

[8] Leslie Katz, “Interview with Walker Evans,” in Art in America no. 59 (March–April 1971), p. 84. — Translator’s note.

[9] Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Reproducibility,” trans. Edmund Jephcott and Harry Zohn, in Selected Writings. Volume 3: 1935–1938, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 2002), p. 109. Italics in the original. — Translator’s note.