As an extension of the Ai Weiwei exhibition at the FotoMuseum (FOMU) in Antwerp, visitors are invited to climb upstairs. On the upper level, the Dutch artist, archivist, and curator Andrea Stultiens presents her glimpses of Uganda. “Glimpses” is the right word. One could refer to “fragmentary history.” In 2011, Andrea Stultiens and the Ugandan artist R. Canon Griffin founded the research platform History in Progress Uganda. The platform aims to build an archival collection of photographic documents as well as bring them to life.

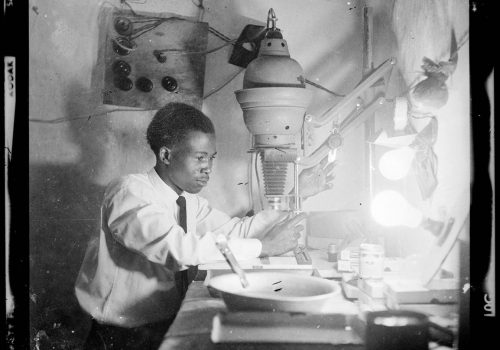

Over six years, History in Progress Uganda has published eight books entitled Ebifayani, literally meaning “resemblance.” In Lugandan, there is no word for photography or painting. The function of representation is used to qualify a variety of artistic media. These publications bring to light the work of little-known, deceased, or forgotten Ugandan photographers, and offer a multi-voiced narrative at the center of Andrea Stultiens’ rethinking of history.

For the lack of a better term, critics call Andrea Stultiens an artist as well as an archivist and curator. She performs the first of these roles by producing a photographic series about contemporary Uganda. Her images feature Ugandan youth, the streets of Kampala, and Westernization. Her second role is the cornerstone of the other two. She collects, assembles, evaluates, and promotes Ugandan photography dating back as far as cameras have been used to freeze time. When she comes across a noteworthy photograph among dusty archives, made by a chronicler of a failed coup d’état, a social worker titillated by the shutter release button and turned official photographer of successive regimes, Andrea Stultiens becomes an editor. A trace of the time regained becomes a memory. In her art center, Stultiens wants her archives to be alive. May the images revive! When Andrea Stultiens put on her curator’s hat, she invited Ugandan artists to transform archival documents into fresh works of art.

Eight books released thus far, and as many spaces in the FOMU exhibition: the sixth installment of Ebifayani reveals the daily life of a Catholic mission founded in Uganda in 1906 by the White Fathers (Pères Blancs). This religious organization was in charge of Catholic education and took part in the dialog between Ugandan peoples. To this day, it continues to exert considerable influence as Vatican’s representative. Andrea Stultiens managed to disarm the order’s distrust and have them relinquish some of their control of images (as we all know, monks and preachers are purveyors of order). In their archives, she has found a series of negatives taken by Canadian missionaries who visited the region in 1940. Admittedly, these images offer an almost endearing picture of the missionaries and their pupils. We see the latter splashing in Lake Victoria. A priest waxes romantic before the vision of eternity offered by a nearby waterfall. The students line up for the camera, all well behaved before the authority of their older Ugandan peers who had recently joined the order. There is a perceptible sense of quietude, but more profoundly, these images seem to bely the historical reality of abuse and violence. There are faces, faces that are flesh and blood. Of course, the colonial violence was there, and no one wishes to deny it, but what we learn from this portion of the exhibition is that, at the same time, there also existed an everyday, ordinary life, refashioned by the colonial rules and authority.

Another book, another chapter. Elly Rwakoma was the official photographer of President Obote. Before that, he photographed proud honeymooners in his capital city studio. The president and the leader of the country’s independence—obtained from the British in 1962—had long left office. So had his successors, but the photographer remained in place. Among the images on display, the exhibition shows the curious ambivalence of media coverage by several Uganda news outlets during the failed assassination attempt against former President Godfrey Binaisa. Press articles contradict one another, lies seem to be everywhere, the truth nowhere, until no one remembers what really happened, and one must scour the archives of local newspapers and muster a lot of willpower to show the relative ambivalence of information. Elly Rwakoma’s photography and Andrea Stultiens’ documentary work tackle this aspect of history.

The final example, where the contemporary takes over the colonial past, is an old image from colonial memory that has been filtered by living artists. 142 years earlier, the British explorer Henry Morton Stanley immortalized the dashing, proud Ugandan king Muteesa surrounded by his henchmen. The image was very popular and circulated throughout the Western world. It fed into the paternalistic curiosity of the West local toward local organizations. The image is still all known and resurfaces amid dusty memories. And yet, it has been erased from Ugandan memory. People are not aware of this image. Upon Andrea Stultiens’ invitation, a group of artists have used it. They have subverted the image, turned it to ridicule, replacing the henchmen with current figures of Western domination. They have dressed the king in modern agbadas. These appropriations enable ridicule, as well as offer a panoramic, plural vision of Ugandan history.

The concept of fragmentary history is at the heart of Andrea Stultiens’ work. She wants to shake free of misguided critiques in the Netherlands targeting what they consider neocolonialist work. The Low Countries can be captious and wrongheaded. Beneath that bad mix of well-meaning sentiments, there is the idea that only a national has the right to comment on his or her country, its history, and its culture. Along these lines, it might be worth warning all the scientists who are fighting Monsanto. The company alone is authorized to talk about GMOs. This digression should be enough to offer a sense of the situation. Andrea Stultiens’ concerns and intentions are a whole different matter. She proposes histories of Uganda. And from that assemblage of history emerges the fragmentary, that is, History. That history has passed through the photographic archive, through micro-history, through individual testimony, through the work of journalism. It is multifaceted, it goes beyond art, and is rooted in complexity. It presupposes that it is possible to understand a country and a society by presenting multiple narratives and histories, in different forms and different formats, all brought together in one place. And when it materializes in an exhibition, this fragmented history has been successful.

Arthur Dayras

Arthur Dayras is a writer specializing in photography. He lives and works in Paris.

Andrea Stultiens, Ebifayani

October 27 to February 18, 2018

Foto Museum Antwerp

Waalsekaai 47

2000 Antwerpen

Belgique