On Thursday October 13, 2016 the W. Eugene Smith Grant ceremony was held at the School of Visual Arts, in New York. That evening, Kathy Ryan, the Director of Photography at The New York Times Magazine, made a speech and told about her experience as a photo editor, her imperishable passion for photography, hunger for discovery and devotion, after several decades in the field. It is a poignant testimony about her job that can inspire young generations of photo editors.

Last March I received an email from Martin Ledford, a high school photography teacher in Santa Monica, California. Every fall he has his students create a book on the theme of “portrait and identity”. He wanted to call my attention to the work of a particularly talented 11th grader,Nico Young, who had made a study of twin classmates. The pictures were brimming with authenticity and emotional depth. They breathed.

It is moments like this that make me astoundingly grateful to have the job I do. Even after more than 30 years of looking at pictures, talking about them, and thinking about them, there are still moments of discovery that stop me in my tracks.

I stared at the twin images puzzling how someone so young could see so clearly. How was he able to translate the chaos of life into single, still pictures with so much emotional power?How was he able to capture such dynamic moments so gracefully? There was a lively improvisational feel to his pictures. You could sense that every time he clicked the shutter, his aim was to convey something true about the person or persons in front of him.

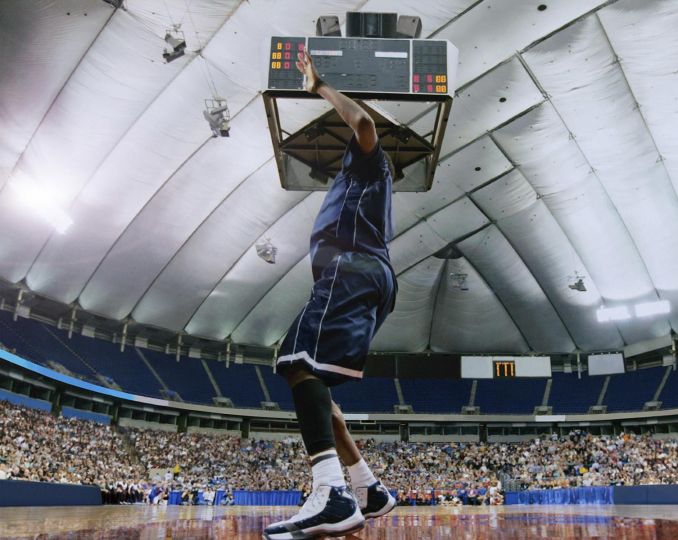

When I showed them to Jake Silverstein, our editor-in-chief, he loved them too. So we gave Nico his first magazine assignment – to show us what life is like at Santa Monica High.He documented the timeless rituals of high school throughout that spring and when the athletes and band members returned to school early for practice, he was there to document them too. We published the portfolio in our Education issue in early September.

Looking at his photos reminds me that photography cannot be too controlled. It cannot be predictable. It should have life and energy and risk. Sometimes that gets messy.At one point during the assignment,Nico asked his teacher when he first visited NYC? So Martin Ledford found some photographs he took when he first went there as a 16-year-old. He took two cameras: a 35mm and a square Holga.

When he showed Nico the photos, Nico asked the strangest question:”Do you think your work was ever as pure as when you were 16?” In his email, Ledford told me he“realized why I love teaching high school.”Mr. Ledford, looking at Nico’s work made me realize why I love being a photo editor.

Another photographer – 70 years older than Nico – has had a profound impact on my thinking about photography. When Bill Cunningham died on June 25th I was heartbroken, as were many of us all over this city. I can’t tell you how wonderful it was to have a Bill sighting at The Times. If you were lucky enough to get on an elevator with Bill , your spirits were lifted for the rest of the day.

If you were lucky enough to have Bill say “Hello young lady!”, better yet. For years Bill said “Hello child!” to me, and then one day it became:“Hello young lady!”There was no one like him. I often go in the Times building on Saturdays or Sundays to shoot some of my Office Romance photos. Whenever I was in the building on the weekend I would see Bill.

He worked 7 days a week. And he worked long days, covering all the evening events, as well as the daytime events, and also coming in to edit and caption the photos during the day. He worked harder than anyone at The Times. He dedicated himself to his craft with a ferocity and devotion that was enviable and inspiring. His work ethic and energy were mind-boggling. He was obsessed with capturing beauty. He once said: “It’s as true today as it ever was. He who seeks beauty will find it.” I hear Bill’s voice saying that whenever I am making my Office Romance photos. He worked right up until two weeks before he died at the age of 87. I want to be like him. I try to be like him.

You may be wondering how Bill’s work connects with the work we are seeing from photojournalists. True he was a fashion photographer and not a photographer who covered humanistic stories in the W. Eugene Smith tradition. But any of us would do well to model our working methods on his. He dedicated himself to his vocation with the same intensity as that of the photographers whose work we are seeing this evening.What Bill shared with them was obsession. He loved his subject – fashion – and he loved all the stylish people who wore it. He was obsessed with telling their story. Nothing got in the way of his obsession.

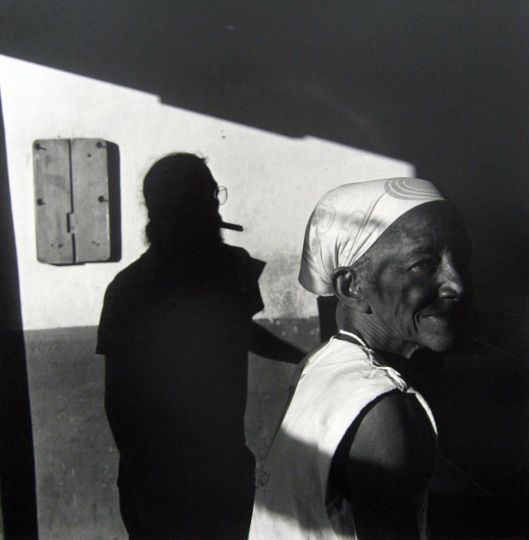

Photojournalists are part of a continuous line that goes back to the Age of Exploration. They spread out across the world, seeking and discovering along the way. They are adventurers as the explorers of the past were. Their filled passports are a messy blaze of color. They spend more time on the road than at home. They make sacrifices – financial and familial – to pursue their craft. But they are not in search of treasure or new science. They are in search of moments that will connect us to our fellow man. They are muckrakers and heart breakers. Troubleshooters, pot-stirrers, and agitators. They can’t be neutral or objective because the mere act of framing the world through a camera lens is a subjective one. W. Eugene Smith said: “The journalistic photographer can have no other than a personal approach; and it is impossible for him to be completely objective.

Even if their hearts and consciences weren’t dictating the way they frame what is in front of them – which of course they are, how could they not be – the artistic decisions photojournalists make guarantee their images will be uniquely theirs. Every photograph is a declaration. The best ones won’t be quiet. They may be silent documents, but they will provoke a dialogue. Sometimes it will be a gentle whisper. Sometimes it will be an uproar.

The age of exploration never ended. The mission changed. Now the explorers cross oceans to explore the geography of humanity. Despite the fact that we are living in a time of globalism and a shrinking world, we need diplomacy and a robust international dialogue now more than ever.

Photographers have a huge advantage over the diplomats at the United Nations with their banks of interpreters. Photographs don’t need translation. They are uniquely suited to bridging the boundaries between cultures and nations. I am not talking metaphorically here. I am talking literally. There is tremendous power in that. We need to use that power now more than ever, because we are living in difficult times.

Amid the torrent of images that hits our eyes each day we can count on photojournalists to make pictures that will rise up out of the swell and have the power to arrest us and make us take notice. They will make images that puzzle us, anger us, and shock us. They will bring home images that show what’s going on past the edges of the ancient maps that used to show what was called “the edge of the world.”

Pictures are expected to have consequences. They are a permanent entente between our moment and the rest of time. In this era defined by selfies and over-sharing, photographers have committed themselves to telling the stories of others. They cannot just stand by and watch the turmoil going on in the world today. They need to explore it and make sense of it. They have the clarity of vision and the purity of heart to do so.

Kathy Ryan

Kathy Ryan is the Director of Photography at the New York Times Magazine.