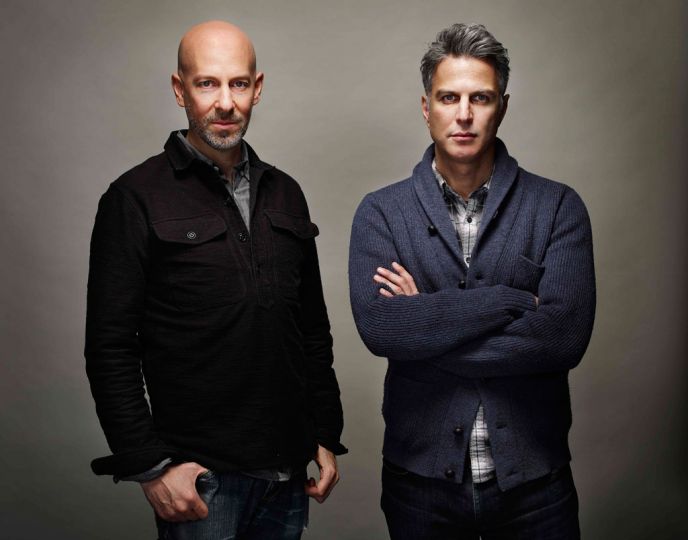

The Kim Jong Phil Command Center is located in midtown Manhattan, in a studio not far from the Lincoln Tunnel. Here, fabricated human bodies are littered about, once used to make a beanbag chair that was inspired by a photograph of prisoners piled up inside the Guantanamo Bay detention camp. There, small bronzes of photographer Phil Toledano cast as Saddam Hussein on horseback and Joseph-Désiré Mobutu. And then there are the paintings of Toledano recast as Kim Jong Il, which were just returned from an exhibition, still lovingly wrapped in packaging. The paintings, recreations from public works, large scale murals that the former North Korean leader imposed on his citizenry, appeals to Toledano’s charming megalomania.

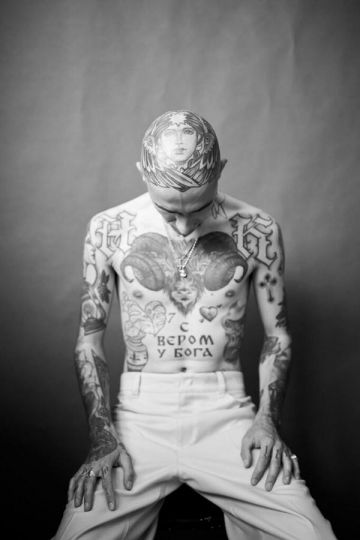

Just as Marshall McLuhan noted a connection between the artist and the criminal, Toledano takes this connection to the highest level. He reveals, “The dictator is like the artist, isolated and living in a biosphere of his own construction, drinking his own urine and believing it to be the finest claret. Just like a dictator, I must live in a closed loop of self-delusion. A place where my words and ideas always ring true. A gilded daydream of grandiosity.”

He continues, “I am always thinking of how I function as an artist. It’s total delusion, complete narcissism. You must convince yourself that you’re making this thing, it’s a new idea the world has never seen before, and that the world cannot wait to hear what I have to say. And that’s not the case at all. But the artist, like the dictator, creates his own world and fills it with believers. He is so isolated, so separate, just a self-contained ideal.

Toledano goes on Google and directs my attention to a photograph of North Korea at night. It is all black but for two or three hits of light, while surrounding countries are lit up like Times Square. Toledano continues speaking about the theme of isolation, in its many forms: physical, political, ethical, luminous isolation. The artist, like the dictator, is alone in the world.

Then he turns to me, and he tells me that when his parents died, everything changed. It wasn’t only that his third monograph, Days With My Father (Chronicle Books, 2010) became a runaway success, that it allowed Toledano to use the camera to connect with his father—and with the world—through a personally felt narrative; it was something else, something more profound than the art itself.

“When my parents died, I felt a light being switch off, and I could see myself in sharp relief,” he reveals. His work took a more introspective turn, as Toledano now stands as a father himself, a parent to a little girl. He uses art to meditate on who he is, who we are, how we know ourselves, and who we think we are. The portrait, as a representation of the idea of the individual, not just the individual themselves, is a continuing thread throughout Toledano’s work.

Toledano works on several projects at a time, moving back and forth between themes, threads, and storylines. Like Kim Jong Il, Toledano sees the portrait as the vehicle for expression, for an extension of his reality and an entrance into the lives of other people. His work shifts consistently between intimate and monumental, much in the same way he negotiates the exploration of his own identity and that of the world around him, more often than not, with tongue planted firmly in cheek. “Humor is leverage,” Toledano determines. “It crowbars things open.”

Indeed, Kim Jong Phil reminds me of George Orwell’s observation, “All art is propaganda.” What makes Toledano charming, and powerful, is how his work reminds us that we are the ones writing the story, for better… or for worse.

Miss Rosen