The first time I heard about Olaf Heine was back around 2010. Over the years, the photographer I first knew for his motto, “I love you, but I have chosen to rock,” became a regular; whenever I was at a big photography event, he would be there. Sometimes with his close friend Thomas Kretschmann, but always part of the Berlin photography scene.

I had the chance to work with Olaf on several occasions and kept learning more & more about his fascinating mix of high-class celebrity portraits of international stars like Bono, Coldplay, Daniel Brühl, and Snoop Dog; his emotionally powerful series Rwandan Daughters; and dreamy urban landscapes shot in Brazil, Hawaii, or elsewhere by the beach, featuring thrilling perspectives from the top of a wave or the front row of a concert. With Olaf’s upcoming shows & books on the horizon, it felt like the perfect time to do a proper recap with him. So read on, and get ready to be swept away!

Nadine Dinter: In the coming weeks, you will showcase two completely different series from your portfolio: Rwandan Daughters and Hawai’i. You shot the first series between 2016 and 2018 in Rwanda, coinciding with the 25th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide and its horrific aftermath. Could you elaborate on the inspiration behind the series Rwandan Daughters?

Olaf Heine: Indeed, both projects seem to be quite different. But then again, as a photographer, I am interested in people’s motivations, actions, the context of their existence, their lives and their stories. It’s the Human Condition, I assume, the things that define and shape our lives, the characteristics and the conflicts, whether they’re personal or professional.

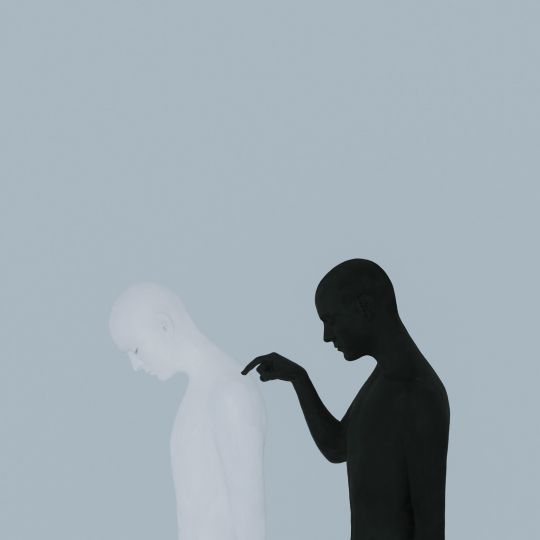

My series Rwandan Daughters is not so much a project about the genocide in Rwanda but rather a portrayal of resilient women who endured systematic abuse thirty years ago. My aim was to address how these women dealt with trauma, pain, and stigma while also showing their capacity for forgiveness, love, and motherhood.

I am curious by nature and want to understand and learn. That’s how my personality works. Exploring emotionally unfamiliar territory and asking questions through my camera are fundamental to how I see myself as a photographer. In Rwandan Daughters, I was compelled by the stories of two generations of women – mothers who were deeply traumatized yet so strong, and their daughters born from rape, who were both in conflict and in dialogue with each other.

Have you ever returned to Rwanda, or kept in touch with the mothers and daughters you depicted?

OH: The genesis of this project arose when I was invited by ora Kinderhilfe and the agency spring brand ideas to volunteer and support their work. The nonprofit organization ora partners with Solace Ministries in Rwanda. Founded in 1995 by a man named Jean Gakwandi, a survivor of the genocide, Solace Ministries provides assistance to approximately 8,000 victims of rape. Jean’s own survival story, having spent three months hiding in a cardboard box in the basement of a house, instilled in him a sense of responsibility toward supporting women, widows, and orphans. Through his organization, he has provided them with medicine, health insurance, trauma therapy, educational opportunities, microcredits, and donations to send victims’ children to school. I keep in touch with these organizations and will collaborate with them again in an upcoming museum exhibition at Kunsthalle Rostock. Our project was first unveiled in 2019, but the onset of Covid in 2020 brought global travel to a halt. Thankfully, we were able to provide partial support to Rwandan women and their daughters in Rwandan during the pandemic through the sale of books and photographs.

Some pieces from the Rwandan Daughters series were shown in Berlin a few years back, eliciting highly emotional feedback and reviews. Now, a collection of new, previously unreleased works will be presented at Kunsthalle Rostock. Considering the evolving political landscape and events that have transpired since the initial exhibition, do you anticipate a different reaction this time around?

OH: I don’t know, Nadine. What’s different now? Do things really change or improve? Look at Ukraine. Or Israel. Or Syria. Or the prisons in Iran. It’s no secret that women often bear the brunt of armed conflicts, subject to gender-specific violence, and that rape is deliberately and systematically used as an instrument of terror. I’m left feeling confused and powerless, seeing little change since what feels like the Middle Ages, with sexual violence against women in modern warfare persisting as a major global issue. So I find it all the more astonishing and admirable that many women continue to take on the tasks of post-conflict cleanup, reconciliation efforts, and even mediation between opposing factions. Despite historically being excluded from power structures and bearing no responsibility for the misery, horror, and terror we witness today, they courageously step up to address the aftermath.

The Rwandan genocide stands as one of the great tragedies of the last century. How do you prepare yourself for such an emotionally charged project, particularly the encounters with the individuals who were directly affected?

OH: Good question. How do any of us prepare for the chasms, the trauma, and the darker things in life? To be honest, I was quite naive when I embarked on this project. Naive regarding the extent of the violence and brutality. Listening to the first stories and descriptions by the victims left me utterly shaken. The mothers carried an immense burden of shame and disgrace; their bodies had become the battlefields for the cruelty of men. The accounts of rape were horrifying, with many victims suffering from infections and pregnancies resulting from the assaults. Many women didn’t want these children and tried to terminate the pregnancies or kill the children after the birth. Who knows how many succeeded in doing so. Amid their pain and trauma, these women – mothers and daughters alike – had to learn how to navigate their relationships and reconcile their differences, often because other family members had perished. While I certainly confronted the darkness and horror of what had happened, my focus remained mainly on the constructive aspects of the project: accounting for the past and the journey toward reconciliation.

Shifting gears to your more known works: You are celebrated for capturing iconic rock musicians like U2, Coldplay, and Sting. Do you use any special techniques or preparations for such high-profile photo sessions?

OH: Luckily, my collaborations with such esteemed artists didn’t materialize overnight but were the result of a 25-year stretch of taking portraits. I started with young, unknown artists and essentially worked my way up the ladder. To me, it has been an organic and fluid evolution of analyzing, learning, and accumulating experience. When you’re young, you run on intuition, and when you’re older, you run on experience, I suppose. Now, it’s a blend of research, genuine interest, curiosity about someone’s work, and my own experience that I bring to each session, helping me to generate ideas. I have a deep interest in what drives other artists, what defines their artistry, their essence, and their creative process.

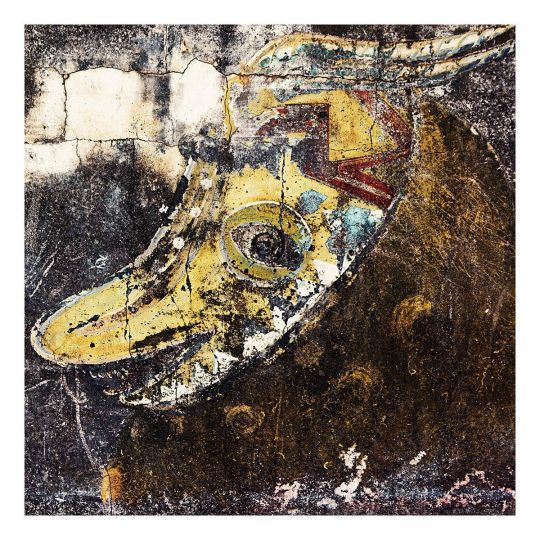

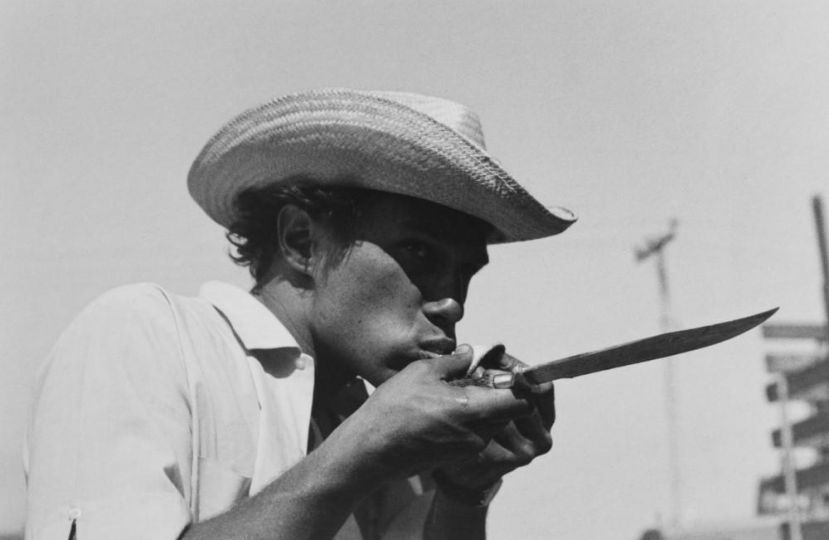

Several years back, you captured a striking portrait of Brazil and its capital. Following your encounter with the legendary architect Oskar Niemeyer, you repeatedly returned to Brazil to document its architecture, people, and natural beauty. Now, you are unveiling your latest long-term project: Hawai’i. Could you share a bit about the idea behind this project and what motivated you to embark on it?

OH: Thank you for your kind words. Actually, I’m presenting both projects. My book Brazil has been out of stock for a while, and the publisher kindly decided to do a second print. I’ve added a few new photographs taken in Brazil over the past years, and we’re printing the book on a beautiful new paper. The design will remain somewhat the same, but the overall presentation will be enhanced. While we were working on the reprint, the idea of publishing my new project, Hawai’i, came up, and we decided to work on both projects simultaneously. Hawai’i is a remarkable place for all kinds of reasons, and I’ve found myself returning to the islands constantly over the last two decades. To quote the great Joan Didion: “I spent what seemed to many people I knew an eccentric amount of time” there. There’s something about the values and sense of community in Hawai’i that speaks to me. I am not sure if it’s the laid-back surf culture, the sunny beach life, the diverse culture of people and places, the Aloha spirit, or the stories, chants, and songs that Polynesian people like the Hawai’ians on those small islands developed over centuries as a method to pass on their codified learnings and understandings. It’s probably a combination of all these elements – the humanity reflected in the Aloha values, the altruistic concept of unity and guidance to share mind and heart, the kindness, generosity, respect, and care without expecting anything in return – all framed by the mind-boggling beauty of Hawai’i. Hawai’i is a place of extremes, one of the most biodiverse and pristine regions on Earth. When I’m there, I feel a profound connection to the genesis of our planet. But the more time I spend on the islands and the more locals I get to know, the more I see beyond the exotic elegance and lushness of the land and nature. It’s like looking through a spyglass and spotting a multitude of issues – an allegory of the major problems of our time: climate change, pollution, inequality, displacement, gentrification, homelessness, racism, etc. That said, I don’t consider myself a photojournalist. I am primarily a portrait photographer, aiming to observe, analyze, characterize subjects or themes, and formulate a narrative from my personal perspective. So, when the idea arose that my photographic work in Hawai’i could be more than just a loose collection of images, I consciously tried to create space for many perspectives on the subject.

During your work on the Hawai’i project, was there a particular encounter that left a lasting impression on you, one that you could share with us?

OH: The most impressive encounters in Hawai’i are always tied to the ocean – whether you’re facing a 12-foot shark or a 12-foot wave. The ocean is always majestic, awe-inspiring, and ever-present. It’s like the hidden architect of Hawai’i. The endlessly shifting, restless waves of the Pacific dictate the rhythm of the islands and their inhabitants. The ocean sustains life here and defines the people – whether fishermen, surfers, or tourists. If I had to sum it up, I’d say the book is about the elemental and the spiritual significance of the sea. I tried to capture and articulate the interaction between humans and nature and the power and values that arise from it. You can observe the cracks of our time and the impact of human activity with the same intensity as the sensuality, diversity, and unspoiled nature. In Hawai’i, you begin to genuinely understand what creation means.

What camera equipment do you typically use for your portrait work, and which camera do you prefer for your travel projects abroad?

OH: Honestly, Nadine, I’m not sure I want to go into that. I understand that it might interest some readers, but quite frankly, that kind of tech talk bores me to tears. After all, Hawai’i is twenty years in the making, and I have used a ton of cameras over that time – from Polaroids to larger formats, from Leicas to Linhofs, from analogue to digital. But in the end, isn’t it all just hardware?

How would you describe yourself as a photographer, considering your work in so many different genres?

OH: Well, I’m not sure I can or even want to describe myself in those terms. But I can share what resonates with me as a photographer: How complex, diverse, and multilayered this world is. Life can be such an adventurous journey – both internally and externally. And it doesn’t move in just one direction. Each situation is different, and every new perspective requires reflection. Life is incredibly expansive, and so is photography. That’s how I see it. The eye doesn’t look only straight ahead; you always see a little to the right and a little to the left, and that’s exactly how I try to move as a photographer. As I said earlier, it’s the curiosity, the urge to learn, to question existing ideas, evoke emotion, cast light on the unknown, or provoke thought through my photographs – that is how it works for me. That’s the fuel that keeps me going. And to be able to use that fuel, my creative voice, as a means of expression, channeling thoughts and emotions, crossing boundaries of language, culture, and time – that’s truly valuable to me.

What’s your advice to up & coming photographers?

OH: Look to the left and the right.

Upcoming shows & book events:

Kunsthalle Rostock presents the exhibition Rwandan Daughters featuring works by Olaf Heine from 17 March to 20 May 2024.

Galerie Camera Work Berlin presents the exhibition Hawai’i featuring works by Olaf Heine from 19 April to 1 June 2024.

The accompanying photo book Hawai’i and a reprint of Brazil will be published by teNeues on 15 March 2024.

Public signing sessions in Berlin:

Galerie Camera Work: Saturday, 20 April 2024, 3 pm

Bücherbogen am Savignyplatz: Saturday, 27 April 2024 at 12 pm

Check out www.olafheine.com and the artist’s IG account @olafheinestudio