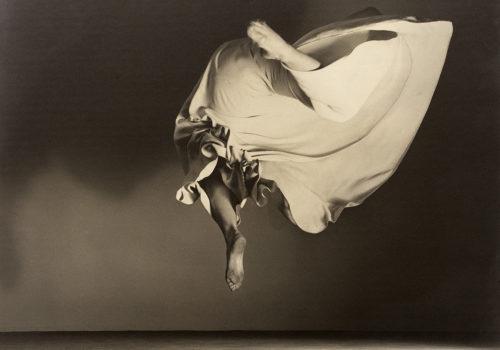

I first met Michael Dressel quite some time ago, while working with Vera Mercer. Dressel, always recognizable by his distinctive black hat, stopped by. Soon after, I was introduced to his powerful black-and-white photography. His stark and unflinching images shine a light on the “invisible” individuals from everyday life who often go unnoticed. Talking with him about his art and perspective was truly fascinating, making the following interview a real pleasure to conduct.

Nadine Dinter: This month, your latest exhibition “The End is Near, Here” will open on July 27, 2024 at Kunsthaus sans titre in Potsdam. Are you excited to unleash this very special selection of works?

Michael Dressel: I have mixed feelings about this one. Obviously, it’s always exciting to put a solo show together, especially when it is accompanying a book release of the same body of work.

In this case, the joy is overshadowed by the theme because it is not exactly a happy one.

I felt the need to express my view of the current situation in the United States just a few months before a fateful election. The political and social climate has reached a truly scary point, and I felt the need to present how it looks to me and how it makes me feel. Insofar as it deals with the concrete outside world at this very moment, it is also deeply personal.

The title of the show (and the book) sounds like a prophecy. After all, on Earth, you have never been afraid of visiting lost places and capturing people who seem to have fallen from grace. What role do you feel has been assigned to you as a photographer?

MD: I hope to be proven wrong in my bleak assessment, but I wanted to point out the distinct possibility of a horrific path into the future. I don’t think that I was given an “assignment.” That is something for journalistic photographers who are sent by media outlets to document a specific event or situation. They are paid professionals, and their images are used by editors to fit the intent of those outlets. I am self-assigned and am also my own editor. I enjoy the freedom and the difficulty of dealing with my work without interference and outside guidance from start to finish.

In your images, we see many homeless people or men & women who lead a different lifestyle, like prostitutes, strippers, and lost souls. What’s your way of approaching them, and how do you manage to take their photograph?

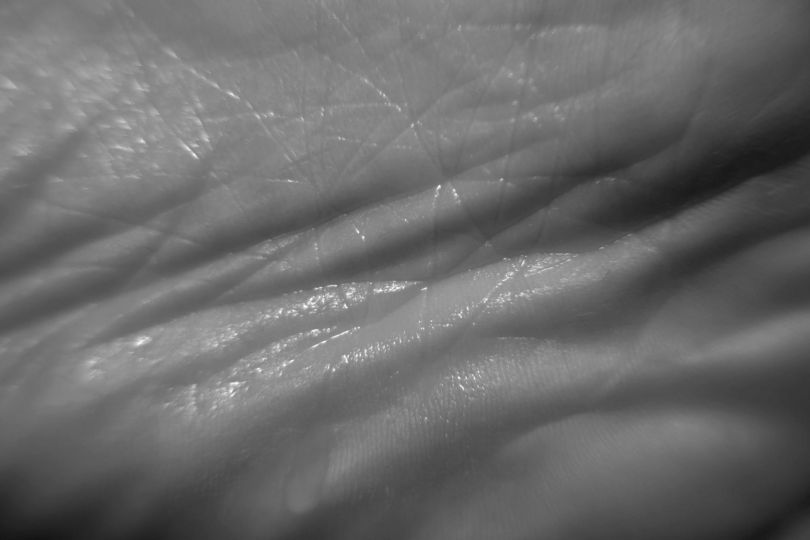

MD: I photograph mostly in public spaces, and that often means the street. I think one of the reasons that so many people who live in precarious circumstances appear in my images has to do with the fact that so many of them are present. When I arrived in the United States it seemed like an ocean of prosperity interrupted by islands of poverty. Nearly 40 years later, I see an ocean of poverty with islands of prosperity. Probably caused by my own life experience, I feel a kinship with people who have endured or are enduring hardship. Many of the people I encounter seem to sense my understanding and offer me basic trust. This instinctive trust, formed instantaneously during extremely short casual encounters, is the precondition for honest, good, and hopefully revealing images. Being out there and having these encounters is a constant self-check for my own humanity. For me, that is as important as the results.

You once said that there are enough celebrity portraits being taken by a variety of photographers, which was why you decided to devote your photography and portraits to the “invisible” ones – to those who go unnoticed and undocumented. Have you always felt like this, or did this philosophy grow in you after having lived & worked in L.A. for many years?

MD: I have the utmost respect for photographers taking images of celebrities. Not an easy job, with its own set of great difficulties. I just never had any interest in that field, even though I encountered many famous people during my film career. It was just nothing I was drawn to. Maybe because, in a situation like this, photographer and subject rarely meet on an even footing. Even though I worked in that world, it never felt like it was my realm or zone of interest.

Do you have particular areas where you like to photograph, i.e., where you find your subjects, or do you rather have your camera with you 24/7 and capture the situations that arise?

MD: I always have a camera at hand, no matter where and when.

Interesting situations can and will occur at any place and time. One has to be ready at all times. When I go out with intent, I like to be at places that have a critical mass of people, meaning enough people to blend in and not draw immediate attention to me.

Your “other me” has been part of the famed Hollywood machinery for many years. Working with Clint Eastwood on sixteen movies, being awarded for your work in “Titanic,” “Letters from Iwo Jima,” and “American Sniper,” and being a very successful sound editor for many years sounds like quite a contrast to what you are doing as a photographer. How do you balance out those two sides of your creativity?

MD: That was easy because my Hollywood career happened to be in the field of movie sound and didn’t really present problems I might have encountered if I had been employed as a commercial photographer. The sound career happened more or less by accident and was a true enrichment because it opened the world of sound to me. At the same time, it gave me the freedom to develop my photography without financial considerations because I made my living in an unrelated job.

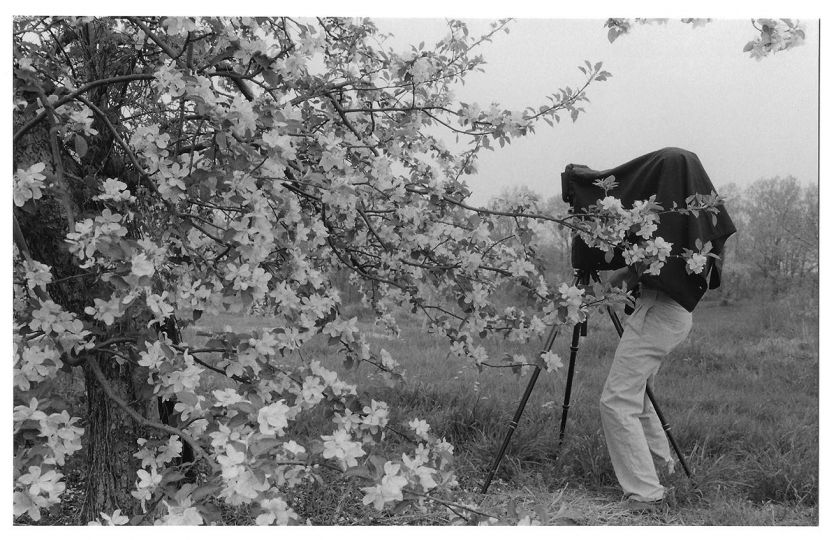

What camera equipment do you use for your portraiture, and which camera for your travel projects abroad?

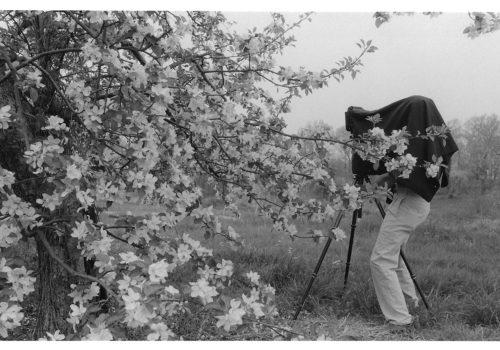

MD: I’m using all kinds of camera brands. By now, the equipment available to most everybody at a reasonable price is of generally high quality. That means the ability of the photographer, not the equipment, is what matters when it comes to taking good photos. I prefer 28 or 35 mm prime lenses. I do not like to use telephoto lenses because, for me, closeness to the subject is of the essence.

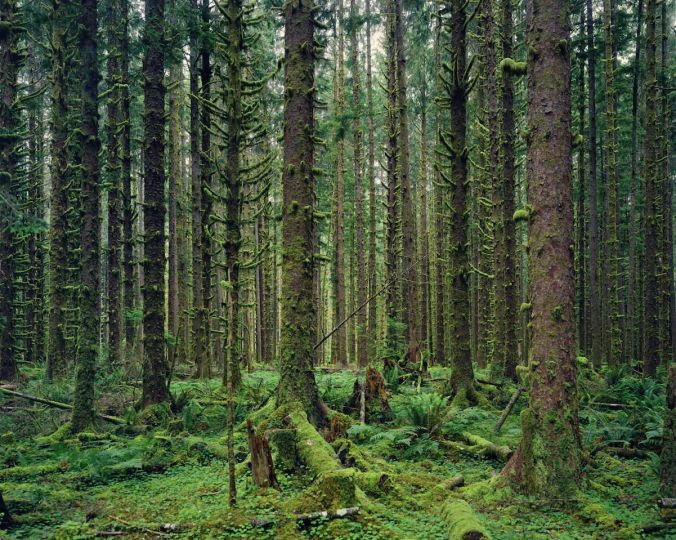

You have worked in Europe, Africa, and Asia. What differences did you encounter, and would you like to share some anecdotes with us?

MD: Every place is different. That’s part of the beauty of doing this. One gets a close impression of the people and their personal and general attitudes. I photograph a lot in Berlin, where many people seem quite tense, angry, and somewhat paranoid. The European laws giving people a right to their own image, even in public places, don’t make things easier. If you take a picture of a child playing somewhere on the street, you feel like you have one foot in prison and risk being confronted by angry parents. In Argentina, people feel proud that you want to take a picture of them and their children and take it as a sign of appreciation. In Japan, people may not like that you photograph them on the street, but they are too polite and conflict-averse to be confrontational about it. They just ignore it and consider you a dumb tourist who doesn’t understand how to behave properly. These are just some examples of how different people react in different places to being photographed.

Is there an image you wish you hadn’t taken and one you are thankful for?

MD: Not really. I prefer to take a photo and decide later that it’s not good enough than not to have taken it. I do remember, though, having taken a photograph in Chicago once that turned out to be life-threatening for me because it captured two drug dealers exchanging money. I hadn’t realized what was going on, and I found myself in a situation in which one of the guys offered in a believable fashion to cut my throat. It took all my interpersonal skills to get out unharmed. I do have quite a few images in my mind I wish I would have taken but wasn’t fast enough. A common experience for most photographers, I’m sure.

Your advice to all up & coming photographers?

MD: Elliott Erwitt said, “Your first 10,000 photographs are your worst.” So go out and photograph things that interest you, things you notice. Don’t wait for “inspiration” to strike. Have a camera with you all the time, not just a phone. Keep going; don’t worry about the “what for” and whether it will be “up to the standards” of what you admire. With time, you will find your own way of seeing your world.

For more information, check out https://michaeldressel.com/ and the artist’s IG account @michael_dressel_la

SAVE THE DATE:

Opening of “The End is Near, here”:

Saturday, 27 July 2024, at 6 pm

Introduction by Michael Biedowicz

27 July 2024 through 8 September 2024

Kunsthaus sans titre

Französische Strasse 18

14467 Potsdam

Wed – Sat 14 – 18 hrs

Sun 13 – 17 hrs

www.sans-titre.de